Today our mobile phones are almost like extensions of our brains, but Harry Yamanaka, 84, still remembers when the very first telephone was installed at Rice Camp at Kipu Plantation on Kauai in the 1930s or 1940s. Rice Camp was

Today our mobile phones are almost like extensions of our brains, but Harry Yamanaka, 84, still remembers when the very first telephone was installed at Rice Camp at Kipu Plantation on Kauai in the 1930s or 1940s.

Rice Camp was a settlement of small, wooden single-wall construction homes on dirt roads provided by Kipu Plantation for its employees, just southwest of Lihue. In those years, the acres of sugar cane grew so tall they camouflaged the plantation houses from outsiders.

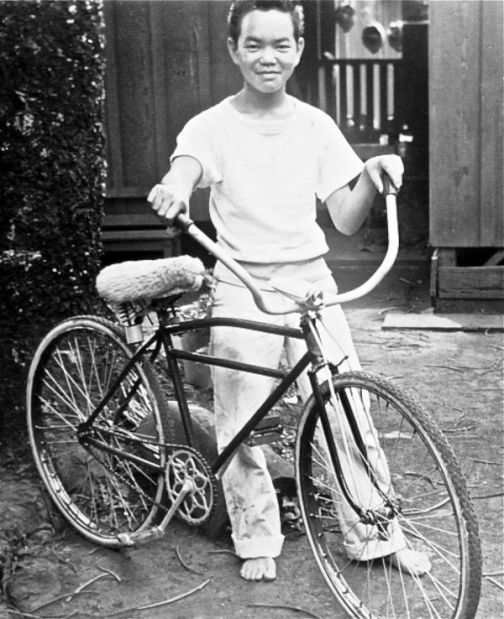

Harry grew up the 10th of 13 children in his family. His father had emigrated to Kauai from Japan at the age of 17 and became a trackman tending the sugar plantation’s railroad tracks. He earned about $35 a month and that was more than many other men.

Harry recalls the day the telephone company came to Rice Camp and selected the home of Mr. Silva, the plantation overseer, for the telephone location. With the plantation manager’s approval, a wooden box was nailed to an outside wall of the house. Rice Camp now had its first phone for everyone to use.

But there was a problem: how to let someone know that a call was for them? One proposal was that Silva’s son, Adam, would personally visit a family when a call came in for them. But Harry says that Adam, a high school student, had no desire to take on this responsibility.

Eventually the decision was made to use international Morse code, a series of audible dots and dashes or “dits” and “dahs,” to signal the first letter of the last name of the family for whom the caller wished to reach. For example, Yamanaka would be represented by Morse code for the letter Y or dah dit dah dah.

“Let me run through a phone call,” Harry says. “The Lihue office of the telephone company receives a call meant for the Yamanaka household about a pending funeral to be held at the Hosoi Mortuary. The Lihue office contacts the Silva telephone and Mrs. Silva receives the call. She sets the phone down on the holding pedestal and toots a loud horn with a dah dit dah dah.

“I hear the horn from our garden,” Harry continues. “I rush home and let my mother know that I will run over to the Silva house to receive the call. I go to the phone booth on the side of the Silva house and take the call. The message is completed.”

And so it was that Rice Camp became in touch with the rest of the world.

“There was hardly any use of a phone in those days. No one used it as a means of gabbing,” Harry says. “If you wanted to pass on information you would walk to that person’s house and let him know what you had to say. Everyone knew that only urgent calls should be made by telephone.”

Harry Yamanaka lived in Rice Camp until he was 18 years old, when he left to attend college in Milwaukee, working until midnight to fund tuition and pay for an apartment. After graduation, he served for three years in the U.S. Navy on a radio repair ship on which he traveled to Russia, Hong Kong, Guam and Singapore.

He returned to Hawaii where he became a teacher and later became an administrator for the Department of Education. After retiring, he taught English in Japan. He now lives in Hilo on Hawaii island.

“I am 85 years old and my life growing up at Kipu Plantation is only memories,” he says. “When I last visited, Rice Camp was still there but the row of green houses where the Yamanaka house stood are gone and only cattle and wild pigs roam that piece of land.

“I can relive that life only in my dreams. But, then, what is life without dreams?”

A longer version of Harry Yamanaka’s memories of growing up in Rice Camp is included Pamela Varma Brown’s “Kauai Stories,” and in Yamanaka’s forthcoming book of short stories about growing up on Kauai being edited by Brown.