One of the most destructive wars in history, World War II destroyed millions of lives and left many European countries scarred. As a child growing up in Yugoslavia, Kauai resident Adolf Befurt was a young boy during the 1940s and

One of the most destructive wars in history, World War II destroyed millions of lives and left many European countries scarred.

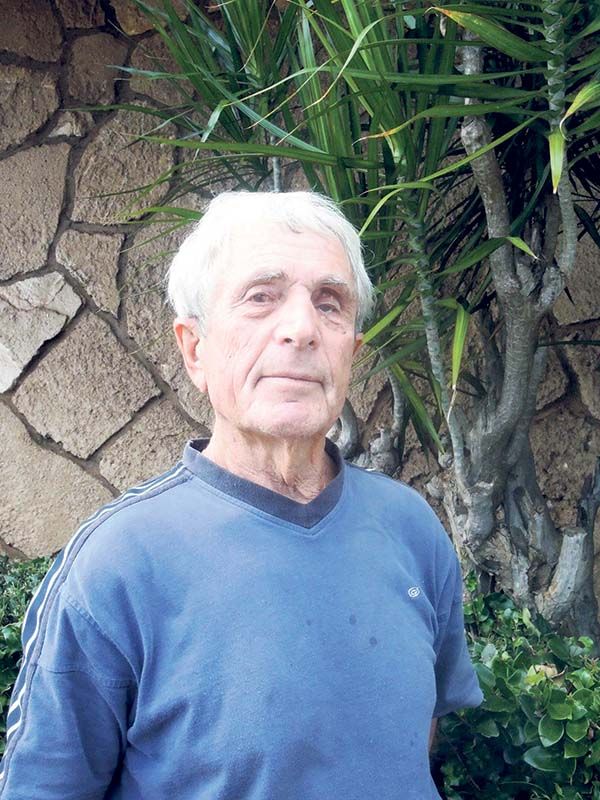

As a child growing up in Yugoslavia, Kauai resident Adolf Befurt was a young boy during the 1940s and has never forgotten the events he experienced.

“I was born July 8, 1936, in a town called Novi Pazar … and when I grew up, it was a town of 6,000 population approximately,” said Befurt. “ It was absolutely rural. I grew up with an outhouse, a well outside, a kerosene lamp, a wood stove and that’s how we lived there, until the Germans marched in in 1940.”

That small, rural town was changed through the introduction of electricity and technology, such as telephones, movies and radios, after the Germans took over.

“It was especially strange to Grandma and Grandpa; they thought it was something unholy going on,” said Befurt. “Somebody put a plug in the wall and here’s that voice coming out of a box … it was really strange. It was like a different continent, a different world.”

The technological advancements also allowed the 8-year-old Befurt and his family to become swept up in the propaganda of the war. But just as they adapted to the new technology, they were forced to flee Yugoslavia.

“We were evacuated by the German military Oct. 6, I’ll never forget that date, 1944, because the war started turning,” said Befurt. “We saw refugees coming like from far, like Romania and places like it … I thought, ‘What is going on? Where are they going?’”

The arrival of the Russian immigrants forced the German military to evacuate Novi Pazar, and place the residents on trains to ship them elsewhere.

“It was a difficult transition, especially for the elderly, now for us young ones, you know for me, it was kind of fun because … my friends were the soldiers … they would take me into the tanks … so of course, for me, it was a lot of fun, but it was not so much fun when we got put into freight; five families and we only were allowed to carry with us what we were able to carry by yourself.”

Befurt and his family were promised they would return to their home in 10 days, but the promise was never fulfilled. Ten days later they were sent to a refugee camp in Austria, where their hardships continued.

“I had a little brother, 8 months old, and he got sick. He died on Christmas Eve,” said Befurt. “It’s still bothering me because we had no help. Christmas Eve 1944, Austria in Braunau am Inn, very kind of strange because that was the town that Adolf Hitler was born.”

TGI: How did you feel about what Adolf Hitler did to the people he hated?

Adolf Befurt: He was just a sergeant in the army. He wasn’t very smart but he had such a personality that he could dupe people into falsehood if they really believed that. Why would old soldier generals of WWII, they were highly educated, … follow a failure? Hitler was not German, he was Austrian. If they would have stopped Hitler in 1940 when he attacked Poland maybe 30 million people would have not died and a continent would not have been destroyed. But the Germans did not have enough courage. Those who did, they died just like any enemy against Hitler.

TGI: What did you think of growing up in the refugee camp?

AB: It was not easy. … The refugee camps, they were so overcrowded. The size of a building like The Garden Island right here, you may have had 200 people in there. We had triple decker beds way in there and no food, and … this one place had one toilet for over 100 people. … We had to cook out in the wintertime. … Everything was on food stamps, that little bit that you got through the government, but it was so little, there wasn’t much. We went around in the countryside and we used to beg the farmers for some food. … My mom got sick at an air raid by the American fighter planes. They flew so low and she got scared and she ran down the hill … and she fell on a branch and she punctured her chest into her lungs.

There was no help. There was no doctor, no medication … she never recovered. It took 11 years and you finally got to the end of it. We smuggled ourselves from Austria on a refugee train, and … my dad made connections with the health sources there were some experimental medicine: shots. She got that but it was too late. They took her into the hospital and six weeks later, she died. It’s so tough because she was only 44 years old. … I couldn’t help my mother or my brother. So then, we smuggled ourselves out of Austria into Germany.

TGI: How did you escape from Germany?

AB: In Germany I worked two jobs in order to pay for my ticket. The church would pay for your ticket as an immigrant but then you would have to work a year on a farm to pay off your ticket for the boat. I was independent all my life even when I was 8 years old. I said, ‘No, whatever will come, I will handle it.’ So, I had enough money, I worked two jobs. I had a little motor scooter that I sold and bought my ticket from Germany to Montreal, Canada. I had $43 that was my whole riches and I only had American dollars. I couldn’t get Canadian dollars … so I spent money on the boat and got off July 4, 1956. I had $36 left out of the $43 and a little pocket dictionary, German/English. I was young, I had a trade. I learned auto body paint business when I was 14 years old in Germany so that was OK. … I had a hard time. I didn’t know the language.

TGI: What was it like for you to adjust from a European culture?

AB: It wasn’t that difficult because there were a lot of other newcomers, immigrants, mostly from Italy … Germans, English, Scotch and Irish, so the place that I worked, there were a lot of immigrants there, and so it wasn’t that hard. But you’re ‘the new kid on the block,’ so you just have to do whatever it takes because you have to find a place to live and you have to pay for your food and all that and I paid $15 a week for board and room. I found this German immigrant family. They were from Romania, who fled the Russians and came to Canada, and so I stayed with them.

TGI: What was it like after you moved to California from Canada?

AB: When I started out (living in America) the most I ever made a week was $30 that you took the tax out of. I needed 50 cents for the bus to and from the job, but I grew up during the war years and after the war years, they were tough. Even after I left in 1956, things didn’t get better until the late ‘50s, early ‘60s for most people because the whole country was destroyed. So they had to rebuild the factories in order to get jobs to the people and housing for the living and hospitals and schools … so it was difficult. I knew I was in a safe country. I had a job and I know there was a future in there. It was a country of opportunity like America still is today.

TGI: What types of jobs did you do while you lived in America?

AB: All my life, for 54 years (my jobs were in) the auto body and refinishing business; bodywork and painting. I liked that because it was a satisfying type of trade. You take something that has a dent in it, you fix it, you make the people happy.

TGI: Is there anything else you would like to tell me about the war or about your experiences?

AB: The war was horrible like any war is … half the world suffered from World War II. World War I was bad but World War II was worse because of the technology that they came to have and many more people died. … but you get over it. You find a new country, like I spent six years in Canada and then I moved to the United States. But I went through the process and that was hard work. I had to have a sponsor … and I had to have a job waiting for me when I came to Sacramento from Canada … I could not get anything from the government; no help for the first three years and I think that was right. This is America, it’s your own country, you make the laws and that was good. That’s why you work harder. … I found my true life in Kauai. I never thought I could live on an island and make it … it’s a wonderful place to grow up and do business.