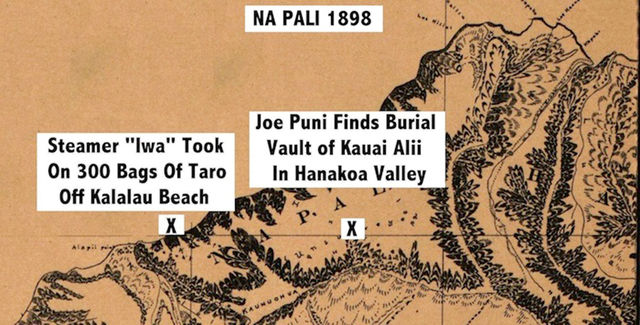

In July 1898, the 16-ton steamer “Iwa” out of Honolulu took on a cargo of 300 bags of taro and 60 bags of rice offshore of Kalalau Beach, Kauai, that had been produced in Kalalau Valley. On that same voyage

In July 1898, the 16-ton steamer “Iwa” out of Honolulu took on a cargo of 300 bags of taro and 60 bags of rice offshore of Kalalau Beach, Kauai, that had been produced in Kalalau Valley.

On that same voyage — “Iwa’s” first trading trip to Kalalau Valley — and in spite of rough seas, the steamer also landed lumber ashore without mishap.

Joe Puni of Honolulu, who along with Harry Crane and James White comprised the hui that operated the “Iwa,” reported that he took an order for more lumber and general merchandise at Kalalau and planned to fill it in a week’s time.

Native Hawaiian residents from Kalalau to Hanalei regarded the advent of “Iwa’s” Kauai trade with joy, since taro grown in that region not sold locally had heretofore gone to rot.

The taro — the finest grown in Hawaii — was in demand at Honolulu poi shops, whose merchants had agreed to take any amount the “Iwa” could deliver.

Consequently, Puni had recently hiked from Kalalau by way of the Na Pali trail to Wainiha and had contracted with farmers along the way to buy all the taro grown in Kalalau Valley, Hanakoa Valley, Hanakapiai Valley, Haena and Wainiha Valley.

During that trip, Puni discovered over 30 skeletons in a cave at the head of Hanakoa Valley — a burial vault for the alii of Kauai, whose bodies after death were taken there long ago by retainers and secretly interred.

While at Hanakoa, Puni also noted that Kinney’s coffee plantation was in fine shape and that Kinney expected to harvest his first crop in August.

Puni, ordinarily a good sailor, became so seasick in the Kauai Channel during “Iwa’s” return voyage to Honolulu that he requested to be rowed ashore at Waianae, instead of completing the journey to Honolulu by sea.

At Waianae, he took the train to Honolulu.