LIHUE — The connection between nene and feral cats is the subject of a new study, published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases, which focuses on the prevalence of the parasite Toxoplasma gondii among Hawaii’s state bird. The study found

LIHUE — The connection between nene and feral cats is the subject of a new study, published in the Journal of Wildlife Diseases, which focuses on the prevalence of the parasite Toxoplasma gondii among Hawaii’s state bird.

The study found that 21 percent of nene have tested positive for past infection on Kauai.

According to a press release from the American Bird Conservancy, the study documented “evidence of widespread contamination of habitat” in Hawaii caused by feral cats.

Greg Sizemore, director of the invasive species programs at ABC, said in their release that, while the organization appreciates cats as pets and acknowledges their role in the lives of people, “it is clear that the continued presence of feral cats is having detrimental impacts on people and wildlife.”

“Before another species goes extinct or another person is affected by toxoplasmosis, we need to acknowledge the severity of the problem and take decisive actions to resolve it,” Sizemore said. “What is required is responsible pet ownership and the effective removal of free-roaming cats from the landscape.”

But members of the Kauai Community Cat Project say the issue isn’t as ubiquitous as it sounds.

The peer-reviewed study was conducted by scientists from the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the University of Tennessee, and the state’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife.

Basil Scott, with Kauai Community Cat Project, said there are many things that threaten nene, and while T. gondii is a threat to the birds, it’s pretty low on the list.

“We understand that toxo is a minor issue,” Scott said. “There are many other things that are more pressing when you look at trying to protect these species.”

Statistics that he received through a public records release from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service show statewide, over the past six years, of the 99 birds tested only six nene died of toxoplasmosis in Hawaii. That’s over 6 percent of the population tested.

The leading cause of death, according to those numbers, was trauma, at just over 18 percent.

“Natural causes — so called — kill more,” Scott said. “Starvation, unknown causes, and bacterial infections kill more.”

The USFWS numbers show 11 birds that died of a different infection or disease, 18 died of trauma, and 15 from emaciation.

Martha Girdany, vice president of the Kauai Community Cat Project, said she only knows of one documented incident where a nene died from toxoplasmosis, and it was in a Mauai zoo nearly a decade ago.

“If there was something else, I haven’t seen it,” Girdany said, “ and I look for that kind of information. I’ve never seen anything else on this.”

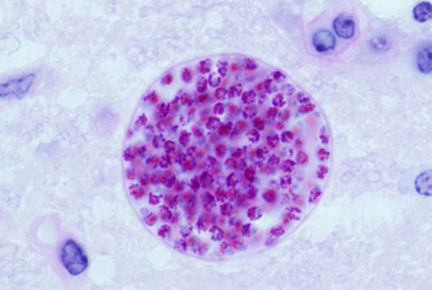

The study pointed to particularly to cats as the perpetuators of the T. gondii, and dubbed it “the most commonly encountered infectious disease” in nene. The parasite relies on cats to complete its lifecycle and is excreted into the environment through cat feces.

According to the release from ABC, a single cat may excrete hundreds of millions of infectious eggs in its feces.

Scott, however, said he’s not convinced it’s just cats that are keeping the parasite in business.

“The cat plays a role, and sure it could be said it’s a key role, but it’s not the dominant form of disease transmission,” Scott said. “In many animals, for instance, it’s transmitted from mother to child. In mice, that rate can be 70 percent.”

Scott, however, maintains that the presence of outdoor cats is a “constant reality” and it’s unavoidable because they’re part of human society.

“Having some populations of outdoor cats is probably good because they keep down rats and mites, which can carry diseases that people actually get sick from,” Scott said. “There’s been no human toxo case in six or seven years.”

He said controlling toxoplasmosis exposure and infection in wildlife and humans starts with controlling the environment, reducing other toxins in the environment, and realizing that other animals carry protozoan parasites that can be similar to T. gondii.

“We’re about working to reduce cat populations, but we don’t agree that zero is the right number,” Scott said. “We agree on less outdoor cats. We know that it helps the birds and we’re committed to that.”