Two years ago, Kauai resident Vaidehi Herbert received an email from Indian conservationist Bharathidasan Subbiah about translating an article from Indian to English for an international publication. “I opened the email, and I finished the translation in the next couple

Two years ago, Kauai resident Vaidehi Herbert received an email from Indian conservationist Bharathidasan Subbiah about translating an article from Indian to English for an international publication.

“I opened the email, and I finished the translation in the next couple of hours,” Herbert said. “I was so touched. He basically saved a vulture chick.”

Herbert and Subbiah stayed in touch. Most recently, Subbiah informed the Kauai translator that he received a conservation award from the International Union for Conservation of Nature on Oahu in September.

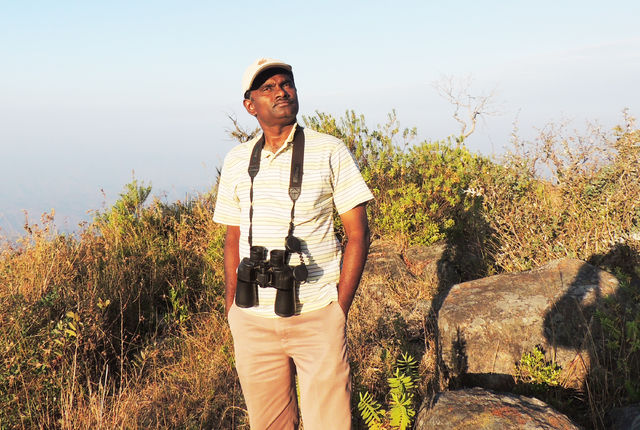

Herbert invited Subbiah to visit the Garden Isle, and the 44-year-old conservationist obliged. He spoke with several dozen students from Island School and Kauai Community College about the importance of conservation.

The native from Tamil Nadu, India, is known in the conservation community for his grassroots work in protecting vultures in Southern India.

With the help of Arulagam (a conservation organization he co-founded) and over 200 volunteers, Subbaiah and his group have improved the population levels of vultures in South India by raising awareness with local legislatures and the local population.

Why are vultures important?

I came to know the shocking news about vultures in decline. No other birds in the recent history has declined this fast — almost 99 percent of the population disappeared.

We struggle to bring them back from the brink of extinction.

It has a very good ecosystem service. It consumes dead carcasses. For example, a group of birds will come and eat a dead elephant. Within two and half days, you’re only left with bones. There’s no contamination of diseases. With a huge population like India, this kind of organism is really helpful. These birds indirectly helps to keep our life better.

Why did the population decline?

Diclofenac has been used for cattle for muscle inflammation, fever and sprains.

This is the main culprit I found all over Southeast Asia. Cows were not used for consumption. Only the skin portion was taken out and they left (the rest of the cow) for vultures and other scavengers. This was the situation.

The drug was introduced in the 1990s. Even after administering this drug, the contamination will be in the body for three weeks. If the cattle dies, the drug has time to transfer to vultures also.

It affects its kidneys and liver and ultimately leads to death. One carcass consumed by 60 vultures, all those vulture are gone. That was the main issue.

Yearly, vultures only lay one egg.

We’re struggling to revive that population.

When did you find out about the bird’s decline?

I got the information from the scientific community. Our work initiated in 2011.

Who found out about this?

Lindsey Oaks was the scientist who discovered this problem.

I got inspired and decided to work to conserve these species.

At the grassroots level, he goes to the villages, meets the village elders, tribes, schools, politicians and livestock inspectors.

Are you seeing an improvement in the vulture population?

The trend is improving. We can’t say it is stopped. The drug is still available for human use.

There is an alternative called Meloxicam for cattle. It takes somewhat longer to cure the cattle.

There are other organizations working in India. We are working in one part.

What’s the population number of vultures now?

We counted about 200-300, which is 1 percent of what it used to be in our area.

There are several thousand in India. Compared to North India, there are somewhat more.

You recently spoke with students at KCC and Island School about the importance of keeping local species like the honey creeper and the shearwater. What did you tell these students they should do to preserve Kauai’s birds?

It’s our responsibility to safeguard these species. It should be up to this generation to save these species for future generations also.

This is the prime, sustainable piece needed. Human beings are a real threat to our whole planet.

What conservation organization do you work for?

Arulagam.org, which means “gracious place.”

You recently took part in the ICUN on Oahu. What award were you given?

They recognized 15 people from all over the world working in hotspot areas. I am one of them. They choose based on our exemplary work. The drug is banned due to our intervention by the government of Tamil Nadu. We passed the resolution in the local parties.

I received the award on Sept. 6 at Bishop Museum.

When you talk about hot spot, what does that mean?

An area rich in biodiversity with critically endangered species. There are certain species that are very essential to the ecosystem. If that species is lost, many other species may emerge. India has two.

Was the drug banned?

In 2006, Diclofenac was banned in Nepal and Pakistan. In 2008, a government order came to India. It was banned for cattle usage, but not banned for human uses. So there’s still a market for leaked drugs for cattle.

What does it do for humans?

If you continue to take this drug, you lose muscular control. My brother used to take this drug in his younger days — now he has kidney failure. I can’t say it is scientifically proven. People need to be careful to use this drug continuously.

If there are people who would like to follow what you’re doing, what are the first steps?

Join groups that are already doing the work and you can learn from them also. We put all of our effort to various aspects we need to cover. We can strengthen the hands of organizations who are doing good work. If your ideologies and their ideologies match, then you can easily work. We have 42 members in our core team, and 200 volunteers from various parts of life.