On the morning of Sunday Dec. 7, 1941, Ikito “Ike” Muraoka and his brother, Mitsugi, were hunting pheasants in Koloa, on Kauai’s south shore. Suddenly, they saw several strange looking warplanes flying overhead. “We sensed that something was wrong, so

On the morning of Sunday Dec. 7, 1941, Ikito “Ike” Muraoka and his brother, Mitsugi, were hunting pheasants in Koloa, on Kauai’s south shore. Suddenly, they saw several strange looking warplanes flying overhead.

“We sensed that something was wrong, so we packed up our shotguns and headed home,” says Ike. “We later learned that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor on Oahu.”

For Ike, a Japanese American, there was no question that he, his brothers and his friends wanted to help defend the United States. Their parents had been among some 200,000 people who had immigrated to Hawaii from Japan to work in the state’s sugar industry between the late 1800s and the 1920s. Another 140,000 workers immigrated from China, the Philippines, Korea, Puerto Rico and Spain.

For those who remained in Hawaii after fulfilling their work contracts, the United States became their home. (Hawaii was a U.S. territory until 1959, when it became the 50th state.)

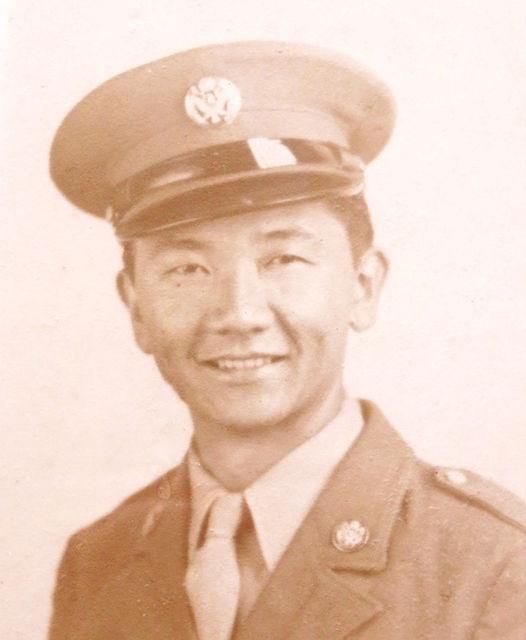

Ike, now a 95-year-old soft-spoken man who lives in a retirement community on Kauai with Nancy, his wife of 70 years, recalls his experiences after Pearl Harbor was bombed that led to his serving in the U.S. Army.

Almost immediately after the bombing, Japanese Americans learned that other people no longer viewed them as Americans.

“The thing that really hurt was that friends of other nationalities turned against us,” Ike recalls sadly, as if his heart is breaking once more. “We Japanese were looked at and treated with contempt and suspicion and kept under surveillance. Racial hysteria was fanned by the other nationalities.”

Wanting to help defend the island, Japanese American men tried to join the Kauai Volunteers, a paramilitary organization that was formed to look after Kauai, complete with uniforms, rifles and bolos (large knives), but they were rejected, Ike says.

Shortly thereafter, it became clear why Japanese had not been allowed membership in the volunteer group.

“We felt that the primary duty of the Kauai Volunteers was not only to patrol the island, but also to place us Japanese Americans under strict surveillance,” Ike says. “We were treated as second-class citizens, even though most of us had been born and raised on Kauai.”

Nevertheless, Kauai’s Japanese American community remained steadfast in their desire to help in whatever manner they could. They soon formed a volunteer group of their own, named the Kiawe Corps.

“Work crews of more than 1,000 of us Japanese, including women and the elderly, turned out every Sunday to clear away the brush and undergrowth, primarily kiawe, between Kekaha and Mana on the west side of the island. It was an area that the military suspected of being scouted as secret Japanese naval landing sites, due to the thick vegetation,” Ike says. Clearing the brush made secret landings impossible.

Our Hearts Were American

One day, in an action similar to events taking place on the U.S. mainland, two Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents came to Ike’s family’s home and searched it.

“Two years earlier, when my father had taken my mother, who was dying of cancer, back to Japan to visit her family one last time, they had brought home a Japanese flag. My father had folded it and placed it inside a chest drawer and forgotten about it,” Ike recollects.

The FBI agents found the flag, and immediately placed Ike’s father, a retired sugar plantation field worker, under arrest. He was charged with treason and taken to jail, where he was held for about 30 days.

“This action traumatized us all, because my father was innocent of treason,” Ike says.

About this time, Executive Order 1966 was signed by the president of the United States, ordering all persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States, even those who were American citizens, to be “evacuated.”

Huge internment camps were hastily built across the country to confine an estimated 120,000 Japanese people, who were forced to live behind barbed wire and under armed guard for the duration of the war. Those who owned property or businesses were required to walk away from everything they had.

Ironically, when the U.S. War Department later decided they wanted more bodies to fight the war overseas, they specifically asked Americans of Japanese ancestry to enlist in the Army. More than 10,000 Japanese Americans did so, the majority from Hawaii.

“For me, personally, I felt that because of the discrimination, and not being trusted because of our Japanese ancestry, that this was one way of showing our loyalty to the United States,” Ike says. “It was not a hard decision.

“You know, there was no anger. We just wanted to prove that we were Americans,” Ike says. “Our hearts were American.”

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was formed entirely of these new recruits, who were Nisei, the first generation of Japanese born in America. The 442nd was soon combined with the 100th Infantry Battalion (formerly members of the Hawaii National Guard), and together they became known as the 100th/442nd.

When the Hawaii recruits arrived at Camp Shelby, Mississippi for training, they met the Japanese American men who had volunteered from the U.S. mainland. But to the Hawaii boys, the young men from the mainland seemed very different.

“There were many fights between mainland Japanese and Hawaii Japanese. I wasn’t involved in any of the fights. I would have gotten beaten,” Ike says, laughing.

“But we finally realized the sacrifice that these Japanese from the mainland were making. They and their families were confined in concentration camps, as we called them, and still they volunteered. That was amazing on their part. Once we realized that, it drew the two groups closer.”

No Time to Get Scared

Once he completed his training, Ike was one of six men in his group who were placed in an impossible situation: After being trained to kill as combat soldiers, they were ordered to become combat medics, and were provided only one week of medical education.

“When we got shipped to Italy, that’s when they told us. We had no choice,” he says, ruefully. “You know what sticks in my mind? That I lost a dear friend during the war because I did not know enough medicine.”

Later that year, in Civitavecchia, Italy, near Rome, Ike was wounded as artillery shells began falling while his unit advanced on a hill. He was in a hospital for nearly one month, “then they sent me back to the unit again.”

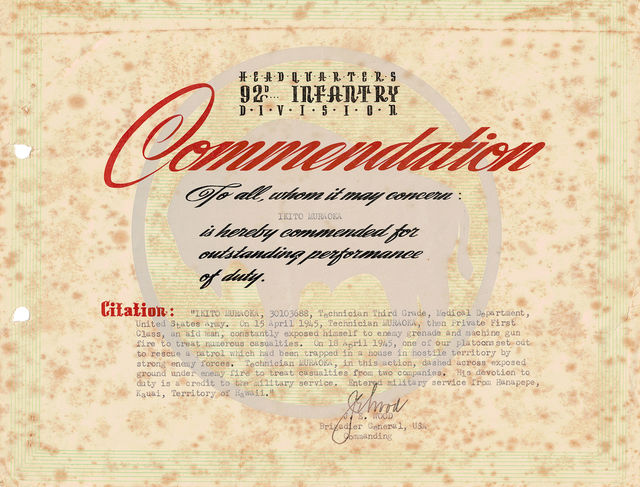

Among his World War II honors, which include his Purple Heart, a Bronze Star and, a Congressional Gold Medal (awarded in 2011), Ike received a Commendation Certificate that paints a picture of some of his heroic actions during the war.

The citation on his certificate states that on April 15, 1945, Ike “constantly exposed himself to enemy grenade and machine gun fire to treat numerous casualties.” Several days later, when one of the platoons set out to rescue a patrol that had been trapped in a house in hostile territory, Ike “dashed across exposed ground under enemy fire to treat casualties from two companies.”

Characteristically, Ike downplays his actions.

“There was no time to get scared,” he said. “The only thinking I did was that I had to get to the guys. If I got scared, I might not have reacted the same way.”

Have Some Peace

Ike says that although “war is a terrible thing,” World War II allowed him and other Japanese Americans to demonstrate the loyalty to the United States that had always been in their hearts.

“I was blessed to survive,” Ike says, with tears in his eyes. “I am thankful that I am here talking to you, and alive, and have a wonderful wife.”

He understands that many younger veterans come home from war angry, but he gently advises learning to see things from a different perspective.

“For the people who are still angry, I would say, ‘Please don’t waste your life being angry. We are here today and gone tomorrow. Have some peace.’

“I can’t think of any other country I would rather be a citizen of or live in, other than the United States of America.”

•••

Pamela Varma is the founder of Write Path Publishing. Visit www.writepath.net