I have had the honor of interviewing and writing about nearly one dozen Japanese American World War II veterans who were born and raised in Hawaii, most of them on the island of Kauai. On the day Pearl Harbor was

I have had the honor of interviewing and writing about nearly one dozen Japanese American World War II veterans who were born and raised in Hawaii, most of them on the island of Kauai.

On the day Pearl Harbor was bombed by Japan 75 years ago, their lives changed in ways most of us cannot even imagine.

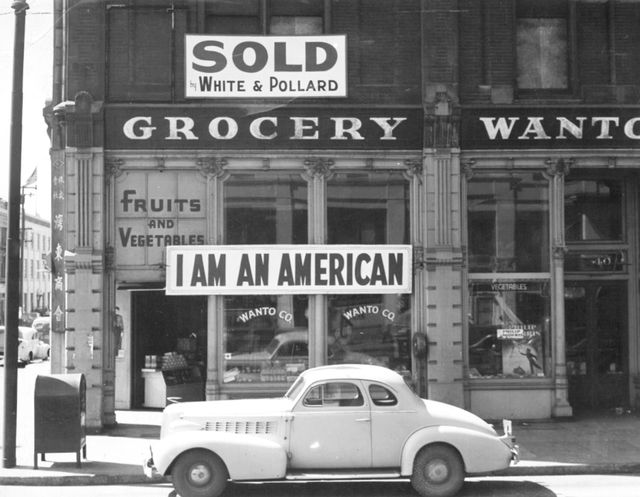

Even though they, and many of their parents, were legal American citizens (Hawaii was then a territory of the United States), they and their families were treated as enemies to our country. Some were jailed on false pretenses; others were locked up in internment camps for the duration of the war. All were subject to discrimination, even by people who had once been their friends.

This echoed activities on the U.S. mainland, where 120,000 Japanese Americans were confined in internment camps across the country, surrounded by barbed wire, with perimeters patrolled by armed guards. All were required to leave behind everything they owned: homes, businesses and any personal belongings beyond what they could carry in one or two suitcases. Most were imprisoned for three years.

Amazingly, rather than becoming consumed with anger, the majority of Japanese Americans responded then — and still do today — with a degree of love and patriotism for this country that is almost unfathomable to most of us, given the hardships they endured.

After first being rejected for U.S. military service and classified as “enemy aliens,” these men responded by the thousands, when the call eventually came from the U.S. government for Americans of Japanese ancestry to join the Army. More than 10,000 men initially enlisted, many of them straight out of internment camps, where their families were still locked up. Thousands more joined soon after.

Together, the Japanese Americans formed the 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team, commonly known as the 100th/442nd. They fought valiantly, and with their motto of “Go For Broke,” they became the most highly decorated units in U.S. military history at that time.

Japanese Americans also volunteered for the Military Intelligence Service (MIS), translating captured Japanese documents for the U.S. government, a service widely credited for shortening the war by two years, saving billions of dollars and at least one million American lives.

The men of the 100th/442nd earned more than 18,000 individual decorations for bravery including 9,500 Purple Hearts, awarded for injuries incurred during wartime, 560 Silver Stars, 4,000 Bronze Stars, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, 21 Medals of Honor and 8 Presidential Distinguished Unit Citations.

Why were these men willing to go to war for the country that had treated them so badly? Because they loved this country.

The few members of the 100th/442nd who still remain alive, can sometimes be seen sitting together at memorial services for their contemporaries, all wearing their shirts embroidered with their motto, “Go For Broke,” made famous after the war, when their heroism and bravery became known.

Kauai resident Norman Hashisaka, who was a member of the Military Intelligence Service, once showed me a quote, published by the MIS Historical Committee in Honolulu, that summed up all Japanese Americans’ participation in World War II:

“Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry. Americanism is a matter of mind and heart.”

Let’s remember that the beauty — and strength — of the United States is the wide range of people and cultures that make up this melting pot.

Let’s celebrate our diversity, and the gifts we each bring to this country.

•••

Pamela Varma is the owner of Write Path Publishing: www.writepath.net