This is the second in a series on the factors relating to the health of the coral reefs globally and around Kauai. Look in upcoming issues of The Garden Island for articles investigating the connection between watersheds and reefs, things

This is the second in a series on the factors relating to the health of the coral reefs globally and around Kauai. Look in upcoming issues of The Garden Island for articles investigating the connection between watersheds and reefs, things affecting reef health, and ways individuals can help save the reefs.

LIHUE — Hawaiian custom recognizes a connection between the watershed and the ocean, mauka and makai; and experts are also looking to the mountains to explain the declining health of coral reefs.

“Everybody has known for a long time this ridge to reef paradigm,” said Ku’ulei Rodgers, coral reef biologist at Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. “The ahupua’a system, for centuries it’s been the central element in Native Hawaiian land management.”

The ahupua’a system, she said, is a land and reef management system that combines watersheds, streams, coastal regions and even some areas further out to sea as an interacting, connected ecosystem.

“They (ancient Hawaiians) had this holistic view. They believed what they did on land was going to affect their fishing and they were careful,” Rodgers said. “We have that same view today. The sustain abilities of the watershed are linked to the near shore environment.”

Though the concept is commonly accepted, it wasn’t until recently that a project between the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology and the Hawaii Stream Research Center quantified the connection between the reefs and the watersheds on a large scale.

“Why do we believe this so strongly? It’s because there are links on the small scale that we were seeing,” Rodgers said.

Research with the Coral Reef Assessment and Monitoring Program was showing these small-scale connections. Established in 1998 by coral reef experts in Hawaii, CRAMP was tasked with creating a statewide network of long-term coral reef monitoring sites, along with a database.

Researchers with CRAMP have worked throughout the archipelago, including the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

The tour took them to the south shore of the island of Molokai, in connection with the U.S. Geological Survey, and there Rodgers said researchers found a “very clear connection between poor land practices and poor reef condition.”

“So because we’ve see in it in certain areas people take it for granted that this is true on a large scale and we couldn’t determine that unless we had a lot of information about both the reefs and the watershed,” Rodgers said.

Rodgers teamed up with Mike Kido, director of the Hawaii Stream Research Center, who created a health index for the state’s watersheds. And working together, they found an overall positive correlation between the watersheds and the reefs.

“So the healthier the watershed, the healthier the reef on a statewide scale,” Rodgers said. “That’s not any surprise because people believed this anyway.”

The explanation of that connection can be found in the water cycle. Henrietta Dula is a geochemist and associate professor at the University of Hawaii who studies submarine groundwater discharge.

“So I study the water cycle and how water from the land gets to the ocean,” Dulai said. “While the water itself is doing that, it carries dissolved material in it.”

Sediment, excess nutrients, pharmaceuticals and personal care products, and pesticides are on the list of things that streams bring down from the mountains.

All those make up local stressors to corals, and add to the global stressors affecting reefs worldwide, said Curt Storlazzi, research geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center.

Local stressors, however, only affect specific areas and are a result of pollution from the land connected to the reef, according to experts.

“If you’re going to affect the watershed you’re going to have to think of the reef that’s adjacent to it,” Rodgers said. “And not all watersheds impact adjacent reefs in the same way. Watersheds have a greater impact on reefs on south shores and in shallow waters.”

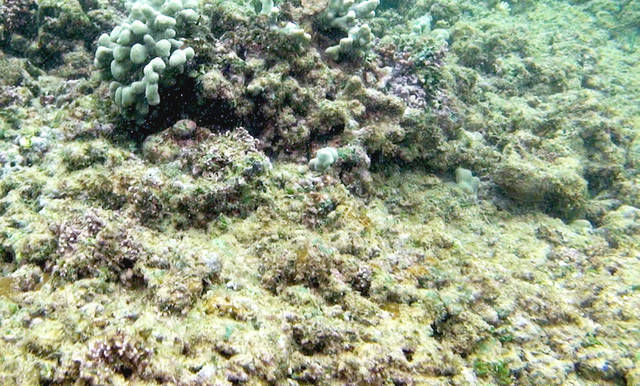

Increased sediment discharge is one of the things that’s inhibiting photosynthesis and can smother coral.

“Islands erode and corals have evolved in connection with that, but not as high a quantities as we’re seeing now,” Storlazzi said.

Invasive plant species have settled into the watersheds that are more prone to landslides. Invasive animal species like goats that eat vegetation, and pigs that dig up the terrain, make the soil more prone to run off with the rains.

“Some of it is sediment from poor land use practices,” Storlazzi said. “It appears some sediment is from taro patches.”

While sediment is enough to stress reefs, it’s usually not alone when it washes down streams onto the coral.

“A lot of time this sediment is a vector for other things, or has nutrients or pesticides associated with it,” Storlazzi said.

Nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous encourage the growth of invasive algae and upsetting the balance of the reef. It also kick-starts a cycle that can lead to a change in the pH of the water, known as ocean acidification.

The declining health of the coral reefs worldwide can’t be attributed to just one thing, experts say. It’s a combination of factors both worldwide and local, but researchers say individuals can play a part in saving the reefs.

In Hawaii, USGS and other entities are doing surveys to inform management agencies that can in turn develop best practices and help curb some of the discharge coming from the streams and going onto reefs statewide.

“People need to start reducing their carbon footprint,” Rodgers said.