LIHUE — Alex Lascon Jr., a Kauai Police Department recruit, said he sees examples every day of how treating people with respect can cool down a situation. “When you show empathy instead of yelling back, it works,” he said. “You

LIHUE — Alex Lascon Jr., a Kauai Police Department recruit, said he sees examples every day of how treating people with respect can cool down a situation.

“When you show empathy instead of yelling back, it works,” he said. “You see it happening out there.”

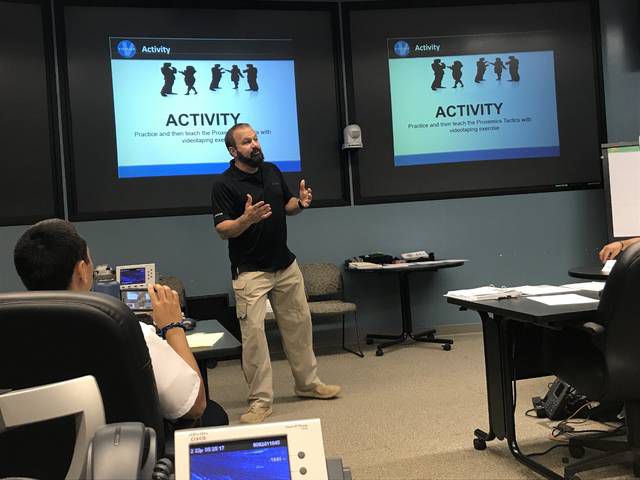

Lascon is one of 13 KPD officers and recruits who are taking a Verbal Defense and Influence class, offered by Vistelar, a Milwaukee-based consulting and training firm that focuses on the entire spectrum of human conflict, from interpersonal discord, verbal abuse and bullying to assault and physical violence.

At the end of the class, participants will be certified to teach the class to the rest of the department, Young said.

The VDI course trains officers in the art of non-escalation by verbal and body language.

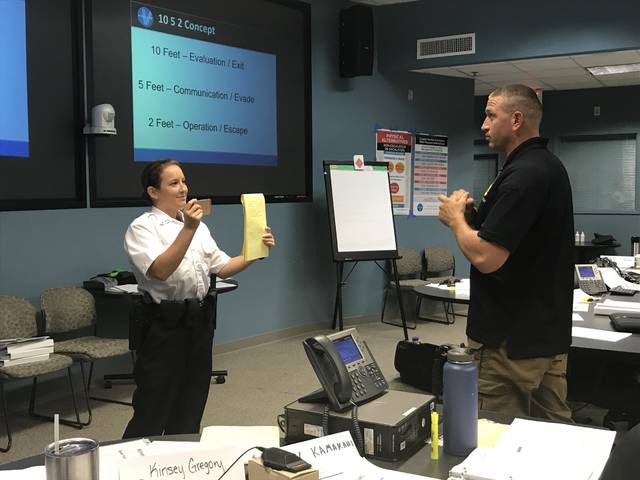

“We do a universal greeting to lie out a non-escalation format,” said Dave Young, co-founder of Vistelar and VDI instructor. “It’s something like ‘Ma’am, my name is Dave Young with the Kauai Police Department, and the reason why I approached you today is because I saw you wandering the hallways, looking a little bit lost. Can I help you?’” he said. “So it becomes a non-escalation tactic rather than ‘What are you doing in the building?’”

The workshop focused on the six C’s — context, contact, closure, conflict, crisis and combat — and how one level can lead to the other.

Young said the goal is to establish communication between a police officer and citizen at the point of contact in a way that is respectful so police officers don’t have to try to de-escalate the situation.

The way to do that is to “listen” with all the senses, he said.

“If you’re just using your ears, you’re not hearing everything,” he said. “So you’re watching my eye contact, listening to my tone of voice and watching my body posture. It’s not just about speaking words, it’s about performing them.”

By seeing the world through another person’s eyes, a person is asking another to do something, not telling them, Young said.

That is key to law enforcement because if someone feels respected, it may prevent conflict from happening, Young said.

For example, during a traffic stop, if a police officer introduces himself and asks the person if they know why they were pulled over, there’s a better chance of that contact ending well, he said.

Even if a citizen is being unruly, if an officer explains their options and gives them time to reconsider their actions, at least the line of communication was clear, he said.

“If I asked you to give me your driver’s license and you said ‘no,’ and then I told you that you needed to give me your driver’s license, and you said ‘no,’ and I grabbed you, legally we’re both right. But morally, we could’ve done better on the communication side,” he said. “So it’s: ask them, explain why, set context, confirm understanding, allow options over threats, and give them time to reconsider.”

Saying no isn’t against the law, but how an officer responds to that response can jump a contact from conflict to combat, Young said.

“The end game is to treat everyone with dignity and respect, and if we all did that, we’d have less hassle,” he said.

John Mullineaux, a training sergeant for KPD, said the class helped him be more aware of his facial expressions while on the job.

“It’s about how you approach people and that universal greeting,” he said. “We have to make sure we put on that face and be positive.”

He also said the class did a phenomenal job in teaching him how to choose words.

“And that doesn’t just apply to police work,” he said.