Talk Story: Steve Perlman

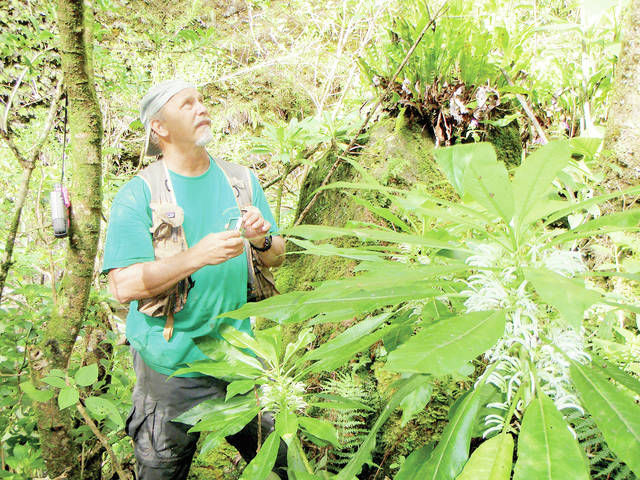

Steve Perlman, a dedicated botanist and the statewide specialist for the University of Hawaii’s Plant Extinction Prevention Program, may be the last hope for Kauai’s rarest plants to survive. With 45 years experience identifying endangered endemic plants, the 69-year-old has collected enough seeds to prevent extinction of some unique species.

Perlman has dropped from helicopters and rappelled down steep cliffs in remote places to preserve threatened plants that support important food chains and could one day become a source of medicine. He has discovered never-before- identified species and gathered vital genetic information for seed banks and greenhouses to perpetuate plants that are disappearing in the wild.

When did you decide you wanted to work with plants?

I loved hiking through Haleakala Crater and going camping. I was always outside in the wildernes.

When I moved back to Kauai in 1971, I got a job at Olu Pua Gardens. They were just getting started in Kalaheo on a little 12-acre garden. I was working there doing landscaping, and one of the things the owners wanted to do was put in a native plant collection. So I wanted to learn about the natives and how to grow them.

How did you get involved with the National Tropical Botanical Garden?

NTBG started up a year-long student intern program, I was in the first class in 1972. Then I became the active nursery man, but I really wanted to go back to school to finish my master’s degree and become a field botanist who collects seeds. The garden had a botanist, Darrel Herbst, who wrote, “The Flora of Hawaii,” so I got to do field work with him. He was with the gardens from 1972-75, and I would climb the trees for him. He did not like climbing trees or cliffs at all, so I’d go out for him. I lived in Colorado for about six months and learned how to do cliff climbing in Boulder. I apprenticed myself to Darrel and learned how he would do his collecting. He knew endangered species before anyone at that time, and for the next 18 years he listed endangered plants for the Fish and Wildlife Service.

What led you to become an exploratory botanist?

I had really good teachers and started discovering new species. I worked an area behind Kalaheo on Kauai in the mountains where no botanist had been past the bog. I found about five or six new species up there hiking alone. That encouraged me to do more and go back for a master’s degree. When I came back, I worked for The Nature Conservancy for about three years all over the state. I teamed up with my favorite field partner, Ken Wood, in the late ’80s. We’ve worked together for almost 30 years and all over the South Pacific. For 20 years, I got to work in the Marquesas Islands and that’s why I’ve written this book from all these adventures. I got to sail down there twice and live there over a year working in Tonga, New Caledonia, French Polynesia, Guam and Micronesia. We finished up with a project in Palau getting dropped on all these rock islands. Working the whole South Pacific was my target area, so I’ve discovered over 50 new species of plants that have been named already and rediscovered a few also that had been thought extinct.

I worked 42 years for the National Tropical Botanical Garden; started in 1972, and then three years ago I moved to the Plant Extinction Prevention Program just cause it focuses more on the critically endangered, and we weren’t getting that much South Pacific work and I had done a lot and I’m getting older too, so I wanted to just focus on Kauai so I didn’t have to travel as much.

Tell us about some of your work.

The clermontia peleana had gone extinct and the only plants we had growing were from seeds I had collected with Ken Wood in the early ’90s. So we went exploring on the Big Island near the Wailuku River. We were able to find five more plants by really hunting around. We had a huge greenhouse project and grew 3,500 of these. We planted where we thought it was extinct and found five more. One of the reasons we got to make it on this big of scale was because of an old friend, Rob Robisho, on the Big Island. He did a project that is a model for the state working with rare plants. He worked with the Mauna Kea Silversword when there were only five plants left. He collected seeds, grew them in the greenhouse, and we outplanted over 11,000 of these.

On the Big Island back in 1989, I discovered and named a species in the African violet family. When I first found it, there were over a hundred of them. Now it’s weedy and got pigs in there, so we’re down to just three plants left and got them all fenced. We don’t give up on any of these plants, because Hawaii especially is selected for these species. Around 250 species got here by one seed inside a bird but evolved for millions of years to the 1,300 species which are native in Hawaii. So if we’re down to just one plant, we don’t give up.

Tell us about your work with one of Hawaii’s most popular endemic plants, Alula.

I really wanted to do cliff work and had a suggestion from scientific adviser, Harold St. John. He asked if I had ever grown brighamia insignus (Alulu), because he had written its monograph and no one had ever grown them at that time. Around 1975 I started looking along the cliffs of the Napali Coast and found there were hundreds with flowers on them. They were setting very few fruits, so they actually needed a pollinator. Their pollinator, the fabulous green sphinx moth of Kauai, was almost extinct. I would pollinate them and started growing thousands. When I started working with the Alula, there were a couple hundred of them, now we’re down to one plant left in the wild after hurricanes, goats and weeds. But we have hundreds planted at Limahuli Gardens. Every year I sent 20 packets of seeds out to different botanical gardens around the world.

Talk about a success, I don’t think this species will go extinct anytime soon.

What is one of the most memorable experiences of your career?

My most fun is actually always doing field work, and my favorite areas were the Marquesas Islands.

No one had ever looked on the cliffs, so our team found like 60 new species of plants in this 20-year project, increasing their known flora by 20 percent. Being on the cliffs a thousand feet above the sea where rocks are falling, you feel like you might really be in danger. But a lot of times you’re just roped in looking down over the ocean, and it’s beautiful discovering things.

I had a lot of fun working with this French botanist, Jacques Florence. I went up this one mountain with him on the island of Fatu Hiva, called Mauna Nui, and no botanist had ever been before. It was very remote and hard to get to, and we just kept finding new species. Jacques was just yelling and he’d stop at a brand new species and I’d pass him up and find another new species. We just found so many new things that day. It was so much fun.

Just recently working with Hank Oppenheimer, we found this brand new species of hibiscadelphus we named stellatus, because it was a stellar species and had stellate hairs. It had never been known from West Maui. So to find a brand new species was so exciting. We went back along those steep parts and found almost 100 plants now. The excitement still goes on, we still find new species, still get them named.

How many plants species have you discovered and named?

I’ve discovered over 50 species. I also have 10 species that are named after me now. Some of those are on Kauai; there’s one named after me called pritchardia perlmanii. They’ll usually use my last name and call them perlmanii.

One in the Marquesas uses my Marqueasan name, Tiva, that was given to me. Not only does it show who found it, but Tiva also means steep, so it describes the terrain where it grows. There’s a plant from the Hauupu Range on Kauai that was named after me in the carnation family and now it’s been discovered in the mountains of Anahola on Kauai.

So how were some of native plants affected by Hurricane Iniki?

Tragically. Hurricane Iniki in 1992 had winds gusting at almost 200 miles an hour. It blew almost all the brighamias off the cliffs of the Napali Coast. There was one plant left on the Houpu Range where there used to be a dozen. Before the last 200 years native plants would have come back. Now we’ve got so many terrible weeds on the island, like the guavas and grasses that were brought in for cattle. After all the trees fell down, what came back was 4-foot-deep molasses grass and strawberry guava. No brighamias can grow there, it’s just solid grass.

Is there anything being done to control invasive plants or is it too difficult to manage in remote areas?

Each island has an invasive species program. On Kauai, KISC (Kauai Invasive Species Committee) teams work with our really bad weeds, but there’s usually not that many of them. Federal funding has gone way down as well. So they do help control some of the really bad weeds, they work very hard on it. But there’s a lot more weed species out of control and just overgrowing our forests, like Kokee and Napali Coast.

Tell us about the new book you recently wrote.

I got the idea when I was working in the Marquesas Islands to write an adventure book. I wanted to include their culture, real places, and the real plants we were working with but include a fictional side. I titled it “Murder in the Marquesas: Adventure Tale of the South Pacific.” I took off about three months to write after our field work stopped.

I got to sail down there twice and had two guys trying to kill us out cliff climbing. I also tie in some of the actual issues that go on, even in Hawaii, where some local people may not understand what we’re doing with our endangered plants. I have one character trying to stop people from taking their plants and making money on them from pharmaceutical companies. I wanted to throw those issues in and the idea we might be trying and protect the plants and set up preserves where they keep their goats and pigs. There are controversial issues about working with endangered plants that I wanted to bring out.

Can you tell readers why your work is so important?

One reason why we should save these species, for me, is they’re just jewels of creation. They evolved here, they are Hawaiian. Before people even came here, there were all these species no one really knew.

Agricultural people came and brought crops and things. If I told people that they were good to eat, at least a lot of my local friends would go “We save um then.” Or I can tell them they may be a cure for medicine, which they may. If we never test them, we’ll never know if they’re the cure for cancer or AIDS or something. They found a plant in Samoa which works on some of these things.

I just love the idea they evolved here, they’re native here. It’s just part of the biodiversity of the planet, like the honeycreeper birds only found in Hawaii and all these insects, like the carnivorous caterpillar and happy-faced spider. These beautiful plant species evolved here, and many colorful flowers are curved to be pollinated by honeycreepers.

Hawaii has the highest endemic percentage of plants anywhere in the world. Over 90 percent of Hawaii’s plants are found nowhere else. We should try to hold on to every one of these species and not lose any.

With the PEPP program I work on, we have 238 rare species that qualify in our program. We’re working with the last of these species, and they’re like family when you work with them for 45 years. When they die, you feel the loss and don’t want anymore to be lost, not even a single species.

What does the future hold for native Hawaiian plants?

We already have the technology to save all these species if we work hard. A part of our problem is funding. Funding from the federal government is drying up, and they are not focusing on conservation as much. But we are still losing these species at a rapid rate.

I think as technology evolves along, it’s going to be easier to save these plants. Now we’re just able to grow thousands of these plants in tissue culture labs to at least hold them for the future. Within the next 20 years, I believe we’re going to be able to grow most of our plants if we can have a piece, even just a leaf.

Right now we’re having to work with pollinating the flowers and trying with plants that don’t fruit very often. So I hope in the future, we’ll have a leaf in our tissue lab to clone hundreds. That part is evolving and getting better to give us hope. We’re also able to store the seeds better than we’ve ever done before. They have seed storage labs here in Hawaii at Lyon Arboretum and also at NTBG.

So if we can at least store these seeds at low temperatures, they may last for a really long time, at least long enough that we can find areas for planting. At least the technology will be getting better and better to save them.

We are storing millions of seeds in labs. I think Lyon Arboretum had like 23 million seeds stored and NTBG has millions. The Lyon Arboretum just opened up a much larger tissue lab with tens of thousands of plants. Funding is tough, but there are people out there who still care.