LIHU‘E — A massive seabird conservation project on Napali Coast is taking wing.

Several governmental, cultural and conservationist groups have teamed up to restore seabird populations at Nu‘alolo Kai, one of Kaua‘i’s most significant cultural and historic sites.

Long the focus of a cultural restoration project by the Na Pali Coast ‘Ohana and state Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of State Parks Archaeology Program, Nu‘alolo Kai sits on the northwest edge of the island. Archaeologicical studies have found that the site served as an early Hawaiian fishing village, occupied continuously for over 800 years beginning in the 1100s.

Studies have also found an abundance of seabird bones at the site, indicating they played a significant role for the community that lived there, as they have throughout the Hawaiian Islands for centuries.

“There’s just great respect for them,” said Sabra Kauka of the Na Pali Coast ‘Ohana. “Many of our chants speak of the importance of the seabirds. They were signs of the health of the ocean, the health of the reef and the health of the community.”

However, as invasive predators like cats, rats and barn owls have spread across Kaua‘i and into Nu‘alolo Kai, seabird populations in the area plummeted, with many species whose bones were found there no longer breeding at the site at all.

In response, several groups — including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Na Pali Coast ‘Ohana, American Bird Conservancy and Archipelago Research and Conservation — have established the Nu‘alolo Kai Seabird Restoration Project to protect the mutually beneficial relationship of the site and seabirds, such as the endangered ‘a‘o and ‘ake‘ake, as well as the ‘ou.

“Nu‘alolo Kai represents a unique opportunity to create a project that underlines the strong links between conservation and Hawaiian culture,” said Andre Raine, science director at Archipelago Research and Conservation, a seabird conservation group. “With native seabirds being under threat throughout Kaua‘i by introduced predators, special sites such as these are critical for their conservation.”

The first step of the project

focuses on the removal and control of invasive predators — primarily, rats, barn owls and feral cats.

Luckily for the conservationists, the cliff walls surrounding Nu‘alolo Kai prevent predators from easily reaching the site, and previous efforts have largely cleared the area of cat populations.

“The geological formation means that it’s pretty well-protected from predators generally, but obviously, rats can get around and up and down cliffs and things … and then barn owls are an aerial predator,” said Helen Raine, executive director at Archipelago Research and Conservation.

These efforts have already seen remarkable success — since predator control was initiated at Nu‘alolo Kai, the ‘ua‘u kani has already naturally recolonized the site, with numbers of breeding pairs growing annually.

“It’s rewarding to see that birds are already returning since cats have been removed from the valley,” said Kimberly Shoback, project manager at Hallux Ecosystem Restoration, the predator-control company responsible responsible for existing feral cat removal efforts.

As the coalition clears remaining predators, members have also begun enticing seabirds to return in greater numbers using a series of speakers playing bird noises.

“If you want to encourage them to expand back to areas where they’ve previously been lost because of predators … if they’re on the way (to breeding grounds) and they hear this very vibrant-sounding colony, they’ll come down and check it out,” Helen Raine said.

Because seabirds tend to return to where they were born to breed, encouraging mating seabirds to settle down at Nu‘alolo Kai would, in theory, encourage future seabird generations to return as well.

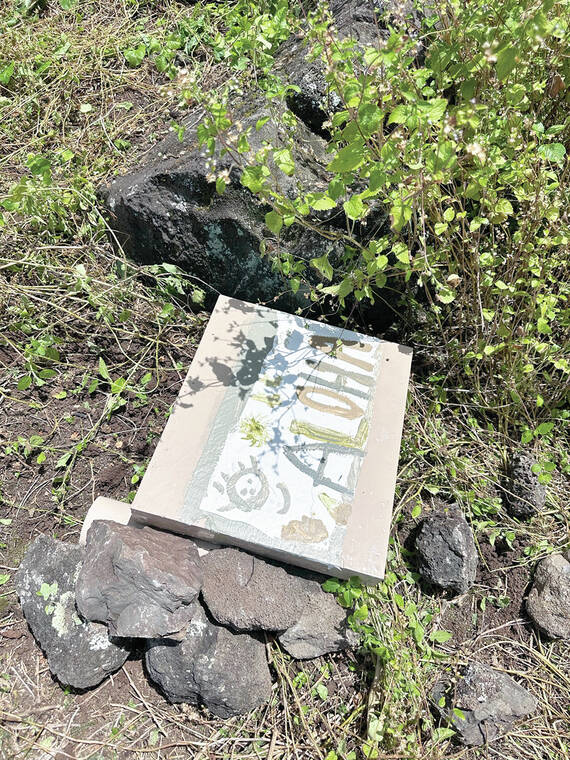

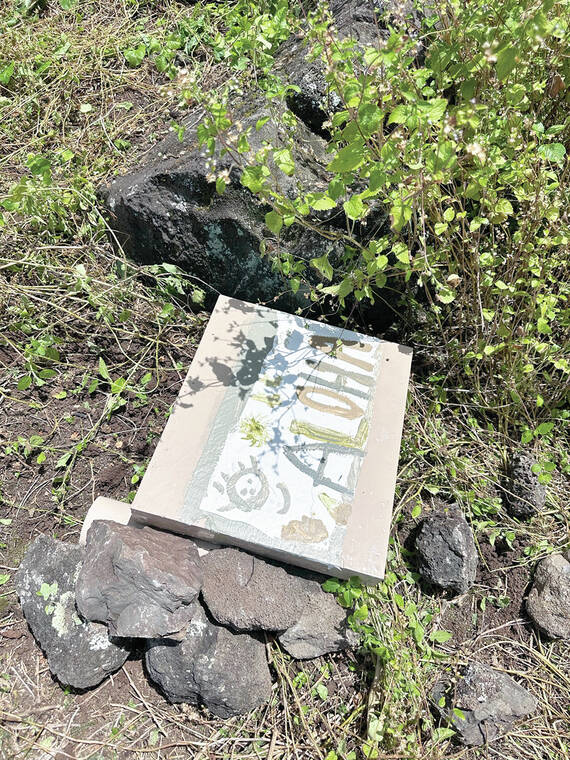

To further encourage the establishment of new seabird populations at Nu‘alolo Kai, conservationists have also placed artificial nests along the site.

“If we can provide them with an artificial burrow that’s already good to go, then it means that perhaps they get successful breeding earlier, and they’re kind of encouraged to stay and to nest together in that site,” Helen Raine continued.

The project’s last branch focuses on educating both visitors and local keiki on the importance of seabirds to Kaua‘i’s history, culture and ‘aina. Project partners are designing informational materials for tour operators, and children from Island School helped paint the artificial nests, with many of Kaua‘i’s keiki visiting Nu‘alolo Kai with the Na Pali Coast ‘Ohana to see the site in-person.

“One of the greatest conservation threats that seabirds face is invisibility,” said Sea McKeon, marine program director at the American Bird Conservancy.

“Most people just don’t have a chance to see and interact with these birds, despite relationships that are centuries long and deeply embedded in ocean cultures around the world. Nu‘alolo Kai is somewhere that relationship — that kinship — can be shown to visitors, while we all learn about the benefits of seabird restoration to Hawai‘i’s ecosystems.”

•••

Jackson Healy, reporter, can be reached at 808-647-4966 or jhealy@thegardenisland.com.

I wonder how many rats are eaten by barn owls versus how many birds?