WAIMEA — Drive across the Waimea River and at any given time you could look to the ocean and see a different river mouth.

Sometimes the river cuts through the right of a sand bar between the freshwater and saltwater. Sometimes it cuts to the left. Sometimes the river is cut off from the ocean and forms a shallow “lake” of freshwater just waiting to meet the ocean.

When that happens, it can trigger flooding in the Waimea Valley and subsequent damage to land and buildings.

Periodically the state Department of Land and Natural Resources contracts a company to remove sand from the river mouth and restore flow back into the ocean, but the results never seem to last long.

In 2011, the river mouth was dredged four times, according to DLNR. It was dredged 40 times in 2017 and 27 times in 2018, always when the river gets plugged up and waters rise to what DLNR’s Resources Engineering Division says is a “critical level.”

Dredging was done again in March 2019 when 15,000 cubic yards of sand were removed from the river mouth and taken to Kikiaola Beach for a sand-replenishment project along that shoreline.

Two days later, the river was plugged up again.

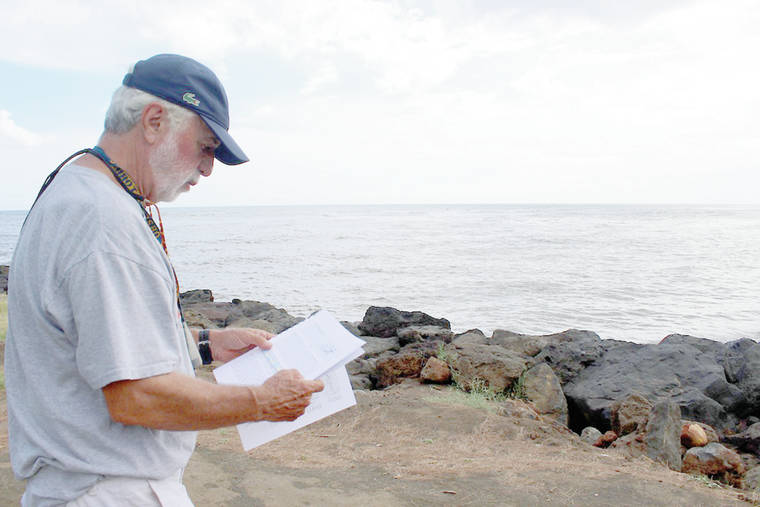

“It didn’t take long,” said Chuck Blay, a geoscientist and sedimentologist who has been studying sand movement on Kauai’s Westside for five years. “The sand bar built back up.”

Blay is working on a project to understand the natural state of the Waimea River in relation to the dredging project. After studying the history and current river patterns and diversions, he says Waimea River has a history of clogging up.

In fact, a blocked Waimea River could have been the deciding factor when English explorers landed on Kauai in 1778.

“He talks about looking for fresh water and identifies the fresh water pool in the Waimea River,” Blay said. “They sent ships and describe a sand bar blocking the water. The sand bar was there in 1778. It’s a natural feature.”

For decades, diversions have lowered the level of water flow in the Waimea River, first by sugar plantations and then by corporate agriculture operating the Kekaha and Kokee ditches.

In 2017, a settlement between community group Po‘ai Wai Ola and the state’s Commission on Water Resource Management started turning gears to return water back to the river system, increasing flow from 16 million gallons per day to around 25 million gallons per day.

Having those diversions in place led to a history of increased sediment in the river, according to Po‘ai Wai Ola, and community members have organized periodic work days to remove that sediment.

High rain events flush some of that built-up sediment downstream to the river mouth, where it accumulates and cuts off the fresh water from reaching the ocean.

Additionally, Blay points out that there’s less water coming down the Waimea River than there was a hundred years ago — the rain gages at Wai‘ale‘ale, which feeds into the Waimea River and others, has decreased from around 400 inches annually in 1912 to closer to 300 inches in current times.

“There’s actually less discharge coming down the Waimea River,” he said.

But there’s more at play than sediment that’s coming downstream in the Waimea River. Kauai has a dynamic combination of currents and wave action that move huge amounts of sand up and down the Westside of the island.

“It’s unpredictable,” Blay said. “Big floods wash the sand out, and waves pick the sand back up and move it in.”

Digging a hole at the mouth of the river just invites more sand in, especially in that dynamic zone of interaction between the river and the ocean.

“Even in relatively normal, 2-3-foot waves, it’s enough to push the sand into the hole you dug in one day,” Blay said.