WASHINGTON — Ten people, including five Russian fugitives, have been charged in connection with malicious software attacks that infected tens of thousands of computers worldwide and sought to steal $100 million from victims, U.S. and European authorities announced Thursday.

The malware enabled criminals from Eastern Europe to take remote control of infected computers and siphon funds from victims’ bank accounts, and targeted companies and institutions across all sectors of American life. Victims included a Washington law firm, a church in Texas, a furniture business in California, a casino in Mississippi and a Pennsylvania asphalt and paving business.

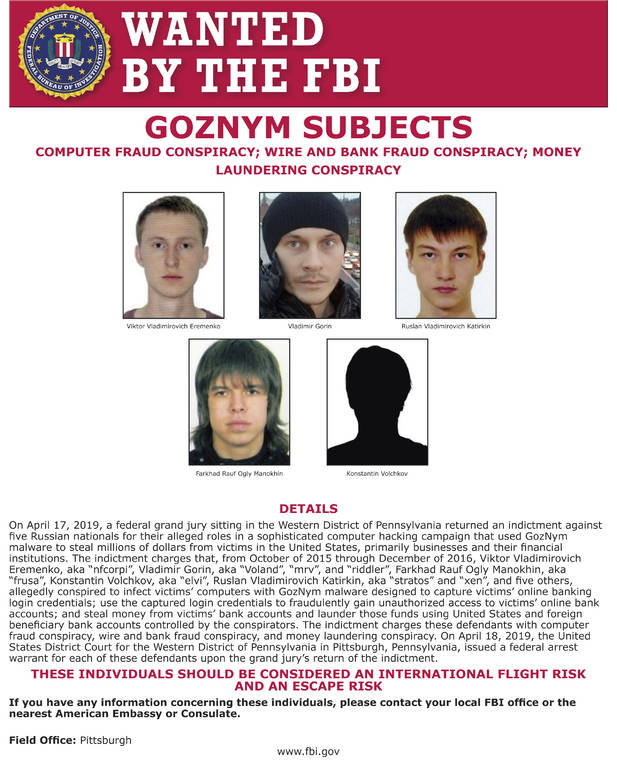

Several defendants are awaiting prosecution in Europe, and five are Russians who remain fugitives in that country. An 11th participant in the conspiracy was extradited to the United States from Bulgaria in 2016 and pleaded guilty last month in a related case in federal court in Pittsburgh, where Thursday’s indictment was brought.

Though the Justice Department has pursued multiple malware prosecutions in recent years against foreign hackers, this case stands out as a novel model of international collaboration , said Scott Brady, the U.S. attorney in Pittsburgh.

Instead of seeking the immediate extradition of all 10 defendants — an often cumbersome process that can take years of negotiations, even in countries that have treaties with the U.S. — American authorities shared evidence with their European counterparts to allow officials in Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia to initiate prosecutions in the nations where the defendants reside.

“It represents a paradigm change in how we prosecute cybercrime,” Brady said in an interview with The Associated Press before a news conference in The Hague with a coalition of a half-dozen countries.

Cybercrime networks “are increasingly targetable” when investigators work together, Robert Jones, the FBI special agent in charge of the Pittsburgh office, said at the news conference. “International cooperation is no longer a nicety, it’s a requirement,” he said.

Other law enforcement officials also said the strategy represents the new face of combating high-tech crime.

Cybercrime has no borders, and criminals have taken advantage of the legal complexities of trying to fight it, said Steven Wilson, head of the European CyberCrime Centre at Europol. “Only through international cooperation can we hope to tackle it,” he said, adding the charges “provide for a safer internet for all of us.”

The charges in the indictment include conspiracy to commit computer fraud, conspiracy to commit wire and bank fraud and conspiracy to commit money laundering.

The investigation was an outgrowth of the Justice Department’s dismantling in 2016 of a network of computer servers, known as Avalanche, which hosted more than 20 different types of malware. GozNym, the malware cited in Thursday’s case, was among the ones hosted on the network and was designed to automate the theft of sensitive personal and financial information.

Law enforcement officials say it was formed by the defendants as they advertised their technical skills in underground, Russian-language online criminal forums. The defendants had different roles within the conspiracy: including developing the malware, encrypting it so it could avoid detection by anti-virus software, mass distributing the spam emails and sneaking in to the victims’ bank accounts.

The leader of the network, authorities say, was from Tbilisi, Georgia, and leased access to the malware from a developer, who in turn worked with coders to create GozNym.

“For the past three years, we have been unpeeling an onion as it were that is very challenging to investigate and identify,” Brady said.

GozNym controlled more than 41,000 computers, officials said. The malware relied on spam emails, disguised as legitimate messages, that once opened enabled the malware to be downloaded onto the machines. From there, the hackers were able to record keystrokes from the victims’ computers, steal banking log-in credentials and then launder the stolen money into foreign bank accounts they controlled.

Brady said prosecutors always look to recover stolen funds, but that is especially challenging in international cybercrime cases.

“Proceeds were converted to bitcoin and without the private key, it is really hard to identify and access, let alone seize, those accounts,” Brady told the AP.

———

Associated Press writer Kristen de Groot in Philadelphia contributed to this report.

Follow Eric Tucker on Twitter at http://www.twitter.com/etuckerAP