Remains of Pearl Harbor sailors return home after 77 years

FILE - In this July 7, 2018 file photo, U.S. Navy sailors fold the U.S. flag draped over the casket with the remains of Seaman First Class Leon Arickx at Sacred Heart Cemetery in Osage, Iowa. Arickx’ remains, which were unidentifiable after his death after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor in 1941, were identified through DNA testing earlier this year. More than three-quarters of a century after the devastating attack killed nearly 2,400 in Hawaii, the bodies of some sailors killed at Pearl Harbor are finally being laid to rest. (Chris Zoeller/Globe-Gazette via AP, File)

FILE - In this July 7, 2018 file photo, U.S. Navy Rear Admiral John Krietz presents a folded American flag to Mark Arickx, nephew to Seaman First Class Leon Arickx, at Sacred Heart Cemetery in Osage, Iowa. Arickx’ remains, which were unidentifiable after his death after the attack at Pearl Harbor in 1941, were identified through DNA testing earlier this year. More than three-quarters of a century after the Japanese attack killed nearly 2,400 in Hawaii, the bodies of some sailors killed at Pearl Harbor are finally being laid to rest. (Chris Zoeller/Globe-Gazette via AP,File)

FILE - In this July 7, 2018 file photo, U.S. Navy sailors remove the casket with the remains of Seaman First Class Leon Arickx from a hearse at Sacred Heart Cemetery where they will be put to rest in Osage, Iowa. Arickx’ remains, which were unidentifiable after his death after the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor in 1941, were identified through DNA testing earlier this year. More than three-quarters of a century after the devastating attack killed nearly 2,400 in Hawaii, the bodies of some sailors killed at Pearl Harbor are finally being laid to rest. (Chris Zoeller/Globe-Gazette via AP, File)

In this undated photo released by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency is Navy Seaman 1st Class William G. Bruesewitz. More than 75 years after nearly 2,400 members of the U.S. military were killed in the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor some who died on Dec. 7, 1941, are finally being laid to rest in cemeteries across the U.S. Bruesewitz, of Appleton, Wis., was killed on the USS Oklahoma and will be buried Friday, Dec. 7, 2018, in Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington, D.C. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency via AP)

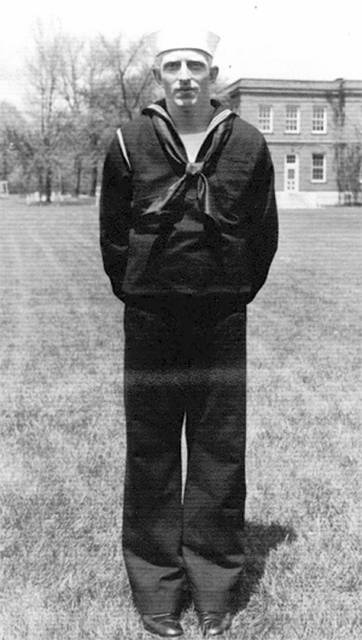

In this undated photo released by the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency is Navy Aviation Machinist’s Mate 2nd Class Durell Wade. More than 75 years after nearly 2,400 members of the U.S. military were killed in the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor some who died on Dec. 7, 1941, are finally being laid to rest in cemeteries across the U.S. Due to scheduling conflicts at the Mississippi Veterans Memorial Cemetery, his family decided Friday, Dec. 7, 2018, the 77th anniversary of the Japanese attack would be appropriate for his burial in his home state, even though people might have to take time off from work to attend, said his nephew, Dr. Lawrence Wade. (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency via AP)

FILE - In this Dec. 5, 2012, file photo, the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu displays a gravestone identifying it as the resting place of seven unknown people from the USS Oklahoma who died in Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. More than 75 years after nearly 2,400 members of the U.S. military were killed in the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor some who died on Dec. 7, 1941, are finally being laid to rest in cemeteries across the United States. After DNA allowed the men to be identified and returned home, their remains are being buried in places such as Traer, Iowa and Ontonagon, Michigan. (AP Photo/Audrey McAvoy, File)

HONOLULU — More than 75 years after nearly 2,400 members of the U.S. military were killed in the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, some who died on Dec. 7, 1941, are finally being laid to rest in cemeteries across the United States.

HONOLULU — More than 75 years after nearly 2,400 members of the U.S. military were killed in the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, some who died on Dec. 7, 1941, are finally being laid to rest in cemeteries across the United States.

In 2015, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency exhumed nearly 400 sets of remains from the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii after determining advances in forensic science and genealogical help from families could make identifications possible. They were all on the USS Oklahoma, which capsized during the attack, and had been buried as unknowns after the war.

Altogether, 429 sailors and Marines on the Oklahoma were killed. Only 35 were identified in the years immediately after the attack. The Oklahoma’s casualties were second only to the USS Arizona, which lost 1,177 men.

As of earlier this month, the agency has identified 186 sailors and Marines from the Oklahoma who were previously unidentified.

Slowly, the remains are being sent to be reburied in places like Traer, Iowa, and Ontanogan, Michigan.

Here’s a look at some of those who have either already been reburied this year or who will be interred on Friday:

———

DURELL WADE

Wade was born in 1917 in the Hardin Town community of rural Calhoun County, Mississippi. He enlisted in the Navy in 1936 and in 1940 re-enlisted for another two-year tour.

His burial in his home state was originally planned for a weekend, when it would be more convenient for people to attend. But because of scheduling conflicts at the North Mississippi Veterans Memorial Cemetery, his family decided the 77th anniversary of the attack would be an appropriate date, even if some people have to take time off, said his nephew, Dr. Lawrence Wade.

He was one of the sailor’s relatives who provided DNA to help identify him.

“My middle name is his name, Durell. My grandson has that name also,” said the 75-year-old retired psychiatrist from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. “I’d gone through my life not really knowing anything about him, other than I carried his name and he was killed at Pearl Harbor. Once this DNA process came along and made it possible to identify his remains, it just made him much more of a real person to me.”

Wade’s siblings included four older sisters and one older brother, according to a bio prepared by his nephew. The Wade children were educated by two teachers hired by their parents to live in the home and teach them until a community school was built on donated property. Wade had written home in September 1941 that he had just taken promotion tests from Aviation Machinist Mate 2nd Class to Chief Aviation Machinist Mate.

His nephew has been planning his funeral. A gospel singer will sing the national anthem. Bagpipes will play. Pilots will conduct a flyover. Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant and Capt. Brian Hortsman, commanding officer of Naval Air Station Meridian, will make remarks.

———

WILLIAM BRUESEWITZ

Renate Starck has been pondering the eulogy she’ll give at the funeral for her uncle, Navy Seaman 1st Class William Bruesewitz, on Friday.

“We always have thought of him on Dec. 7,” she said. “He’s already such a big part of that history.”

Bruesewitz, of Appleton, Wisconsin, will be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, near Washington, D.C. “It’s a real blessing to have him returning and we’ve chosen Arlington because we feel he’s a hero and belongs there,” Starck said.

About 50 family members from Wisconsin, Florida, Arkansas and Maryland will attend.

“We were too young to know him but we’re old enough that we felt his loss,” Starck said. “We know some stories. There’s this stoicness about things from that time that kept people from talking about things that hurt.”

Bruesewitz’s mother died in childbirth when he was 6 or 7, Starck said. Her father and Bruesewitz were close brothers. When Bruesewitz was 14, they built barns in Wisconsin, Starck said. They were educated in Lutheran schools.

———

WILLIAM KVIDERA

Hundreds of people filled a Catholic church in Traer, Iowa, in November for William Kvidera’s funeral.

The solemn ceremony in his hometown included full military honors, the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier reported .

“It’s something like a dream,” his brother, John Kvidera, 91, said.

John Kvidera was 14 when he found out about the bombings at Pearl Harbor and remembers huddling around a radio to find out what was going on. The family initially received a telegram saying William, the oldest of six siblings, was missing in action.

A telegram in February 1943 notified the family of his death.

———

ROBERT KIMBALL HOLMES

The remains of Marine Pfc. Robert Kimball Holmes were interred in August in his hometown of Salt Lake City.

“It’s strange, isn’t it, to be here honoring a 19-year-old kid killed 77 years ago,” nephew Bruce Holmes said.

Only one person in attendance at the graveside services — another nephew and namesake Bob Holmes — had any personal memories of the Marine, The Salt Lake Tribune reported .

The younger Bob is now more than four times older as the sailor when he died. He remembers his uncle coming home on leave in the summer of 1941 when he was 6 years old.

Bob Holmes recalled talking to a friend of his uncle who served with him on the Oklahoma: “He said, ‘One of the things that I remember most about Bob is that he had this attitude. Not just a Marine attitude, but a Holmes boy attitude — defiance, aggression and don’t-mess-with-me.”

———

LOWELL VALLEY

For 20 years, Navy Fireman 2nd Class Lowell Valley’s brother worked to identify USS Oklahoma sailors.

Now that Valley has been identified and his remains have been returned home to Ontonagon, Michigan, Bob Valley expects his role in helping identify a group of 27 sailors will soon be over. All 27 have been located.

Lowell Valley was buried at the Holy Family Catholic cemetery in July, the Iron Mountain Daily News reported.

———

LEON ARICKX

More than 76 years after he died, the remains of Navy Seaman 1st Class Leon Arickx were buried on a brilliant summer day at a small cemetery amid the cornfields of northern Iowa.

Hundreds gathered in July for Arickx’s graveside service at Sacred Heart Cemetery outside Osage, Iowa, in a sparsely populated farming region just south of Minnesota, where Arickx grew up. Among them was his niece, Janice Schonrock, who was a baby when Arickx died.

“My family talked about him all that time,” said Schonrock, 77. “I felt I knew him because everyone talked about him.”

Although they didn’t have Arickx’s remains, his family held a memorial service and placed a grave marker at Sacred Heart Cemetery in 1942. When his remains were finally returned, they were buried at a site not far away.

Schonrock said her family appreciates the work it took to identify her uncle, but she believes it’s essential to identify as many service members as possible.

“I think we need to honor these people who give their lives to our country and bring them back to their home country where they can be close to family who can honor them,” she said. “No one should be left behind.”

———

Associated Press writers Jennifer Sinco Kelleher in Honolulu and Scott McFetridge in Des Moines, Iowa, contributed to this report.