HONG KONG — Scientists and bioethics experts reacted with shock, anger and alarm Monday to a Chinese researcher’s claim that he helped make the world’s first genetically edited babies.

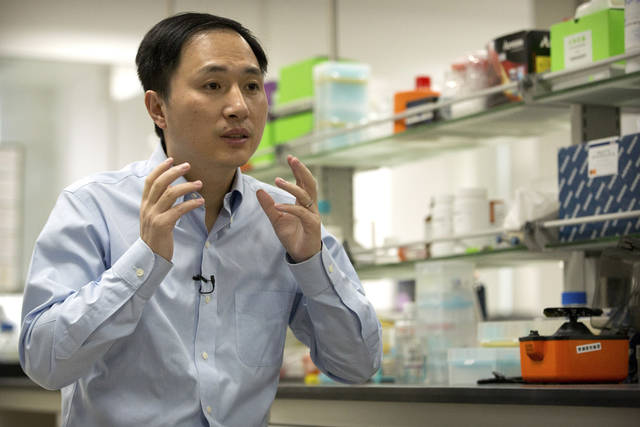

He Jiankui of Southern University of Science and Technology of China said he altered the DNA of twin girls born earlier this month to try to help them resist possible future infection with the AIDS virus — a dubious goal, ethically and scientifically.

There is no independent confirmation of what He says he did, and it has not been published in a journal where other experts could review it. He revealed it Monday in Hong Kong where a gene editing conference is getting underway, and previously in exclusive interviews with The Associated Press.

Reaction to the claim was swift and harsh.

More than 100 scientists signed a petition calling for greater oversight on gene editing experiments.

The university where He is based said it will hire experts to investigate, saying the work “seriously violated academic ethics and standards.”

A spokesman for He said he has been on leave from teaching since early this year but remains on the faculty and has a lab at the university.

Authorities in Shenzhen, the city where He’s lab is situated, also launched an investigation.

And Rice University in the United States said it will investigate the involvement of physics professor Michael Deem. This sort of gene editing is banned in the U.S., though Deem said he worked with He on the project in China.

“Regardless of where it was conducted, this work as described in press reports violates scientific conduct guidelines and is inconsistent with ethical norms of the scientific community and Rice University,” the school said in a statement.

Gene editing is a way to rewrite DNA, the code of life, to try to supply a missing gene that is needed or disable one that is causing problems. It has only recently been tried in adults to treat serious diseases.

Editing eggs, sperm or embryos is different, because it makes permanent changes that can pass to future generations. Its risks are unknown, and leading scientists have called for a moratorium on its use except in lab studies until more is learned.

They include Feng Zhang and Jennifer Doudna, inventors of a powerful but simple new tool called CRISPR-cas9 that reportedly was used on the Chinese babies during fertility treatments when they were conceived.

“Not only do I see this as risky, but I am also deeply concerned about the lack of transparency” around the work, Zhang, a scientist at MIT’s Broad Institute, said in a statement. Medical advances need to be openly discussed with patients, doctors, scientists and society, he wrote.

Doudna, a scientist at the University of California, Berkeley and one of the Hong Kong conference organizers, said that He met with her Monday to tell her of his work, and that she and others plan to let him speak at the conference Wednesday as originally planned.

“None of the reported work has gone through the peer review process,” and the conference is aimed at hashing out important issues such as whether and when gene editing is appropriate, she said.

Another conference leader, Harvard Medical School dean Dr. George Daley, said he worries about other scientists trying this in the absence of regulations or a ban.

“I would be concerned if this initial report opened the floodgates to broader practice,” Daley said.

Notre Dame Law School professor O. Carter Snead, a former presidential adviser on bioethics, called the report “deeply troubling, if true.”

“No matter how well intentioned, this intervention is dangerous, unethical, and represents a perilous new moment in human history,” he wrote in an email. “These children, and their children’s children, have had their futures irrevocably changed without consent, ethical review or meaningful deliberation.”

Concerns have been raised about how He says he proceeded, and whether participants truly understood the potential risks and benefits before signing up to attempt pregnancy with edited embryos. He says he began the work in 2017, but he only gave notice of it earlier this month on a Chinese registry of clinical trials.

The secrecy concerns have been compounded by lack of proof for his claims. He has said the parents involved declined to be identified or interviewed, and he would not say where they live or where the work was done.

One independent expert even questioned whether the claim could be a hoax. Deem, the Rice scientist who says he took part in the work, called that ridiculous.

“Of course the work occurred,” Deem said. “I met the parents. I was there for the informed consent of the parents.”

———

Marilynn Marchione can be followed at MMarchioneAP

———

This Associated Press series was produced in partnership with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.