LIHUE — Sea level rise has already triggered flooding and coastal erosion on Kauai, with king tides reaching record levels and experts mobilizing communities to plan for the future.

Now scientists are saying residents should brace for sea level rise to affect twice the area previously predicted — and models show it’s not just going to flood on the coast.

“It’s important that we identify land areas vulnerable to sea level-related hazards because, if left unmanaged, flooding, wave inundation and erosion will continue to encroach upon coastal lands that are typically heavily developed,” said Chip Fletcher, co-author of a study by a team of researchers from University of Hawaii at Manoa and the state Department of Land and Natural Resources.

The study was published in the nature journal “Scientific Reports.”

“Preparing for these effects will be very costly and take a long time to implement,” Fletcher said. “With these results, stakeholders of all types are now able to establish empirically-based adaptation policies.”

In the fall and winter of 2017, Hanalei Bay at Black Pot Beach Park was eroding more than usual, causing county officials to close part of the beach to vehicular traffic while crews cleared roots and chopped trees in danger of toppling.

That was before April floods wiped out most of Black Pot Beach Park and destroyed parts of Weke Road. But it’s an example of an area where scientists say studies are needed to see if and how ocean patterns are changing.

In July, a study by the University of Hawaii showed one-third of the state’s shorelines are vulnerable to sea level rise.

July also kicked off a series of Westside meetings looking at climate change impacts. Residents met with county officials and researchers from UH-Manoa and discussed community vulnerabilities.

Because of initiatives like that assessment, Kauai is garnering a reputation for proactively looking at sea level rise and related impacts, said Makena Coffman, director of the Institute of Sustainability and Resilience at UH-Manoa.

“Kauai has been a leader in proactively addressing climate change in Hawaii, and there is much more to do,” Coffman said in a press release.

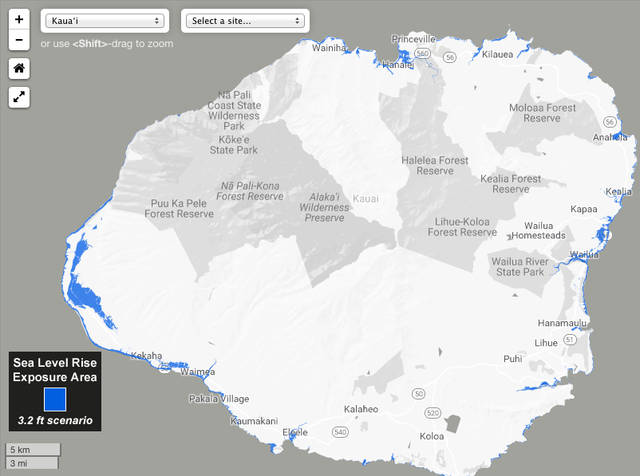

Hawaii has developed a sea level rise viewer, which shows what the state would look like with sea level rise of up to 3.2 feet, looking at exposure area and economic loss.

The prediction has been that sea levels could rise more than 3.2 feet by mid-century.

At 3.2 feet of sea level rise, parts of Kuhio Highway in Wailua, for example, would be flooded, as well as areas around the Konohiki Stream in Kapaa and the lowlands mauka and makai of Kuhio Highway in Kapaa.

That’s just the Eastside. The viewer shows impacts in Anahola and Kilauea, Kalihiwai and Hanalei, and flooding in Eleele, Salt Pond and Waimea.

But that’s not the full picture, according to the newest study out of UH.

Researchers in previous studies assessed impacts using the “bathtub” model, wherein a static sea level surface is projected onto a terrain model.

The method offers a good first look into impacts, but “underestimates the full extent of potential damage, particularly on Hawaii’s high-energy coasts,” according to lead researcher Tiffany Anderson.

Researchers say as sea level rises, several processes are at work — coastal erosion results in permanent land loss; annual wave flooding rapidly escalates past a critical point; groundwater inundation and storm drain backflow create new wetlands and cause urban flooding.

The team also found that the risk of flooding isn’t necessarily just next to the shoreline.

“Low-lying areas where sea level rise causes the groundwater table to rise up to the surface” are also areas of concern. “These areas can be located one to two miles inland from the coastline,” Anderson said.

Anderson and team are incorporating historic rainfall totals into the computer model to determine how sea level-related flooding might be exacerbated during rainfall events that occur during high tides. Hawaii Sea Grant, also located at the UH School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, and Tetra Tech Inc., are helping guide state and county agencies in considering this new data in future planning.

•••

Jessica Else, environment reporter, can be reached at 245-0452 or jelse@thegardenisland.com.

Seriously, who actually believes this garbage?

The sand is always on the move. Lumahai Beach is a good example of seasonal movement. Pinetrees is an example of long term movement. The guardrail in the parking lot was put in when ocean moved up too the trees. Beach came back. Don’t build on the edge. It’s always alive with change.

Every one, as residents and visitors to the islands, need to be aware of our collaborative responsibilities to “malama aina” because of the limited carrying capacities which are part and parcel of the limitations imposed upon the finite resources that we share and need to protect and preserve. Awareness programs and careful monitoring of the ways in which we use what we have cannot be left up to “chance”. When, where, and how it may be possible to work together in unison to be “pono” with our environment, we should embrace those opportunities! This responsibility truly is from “cradle to grave” for all of us!