PAHOA, Hawaii — Many rural residents living on an erupting volcano in Hawaii fled the threat of lava that spewed into the air in bursts of fire and pushed up steam from cracks in roadways Friday, while others tried to get back to their homes.

Officials ordered more than 1,700 people out of Big Island neighborhoods near Kilauea volcano’s newest lava flow, warning of the dangers of spattering hot rock and high levels of sulfuric gas that could threaten the elderly and people with breathing problems. Two homes have burned.

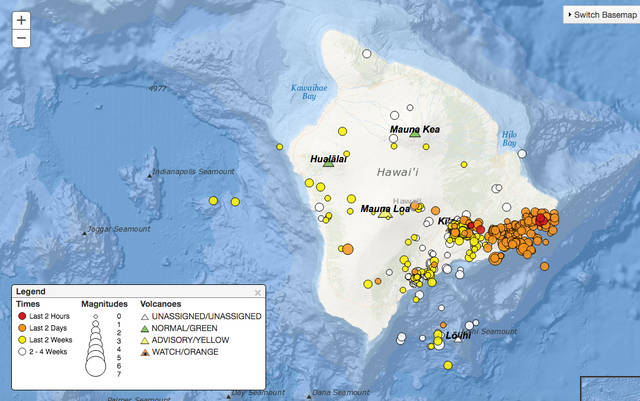

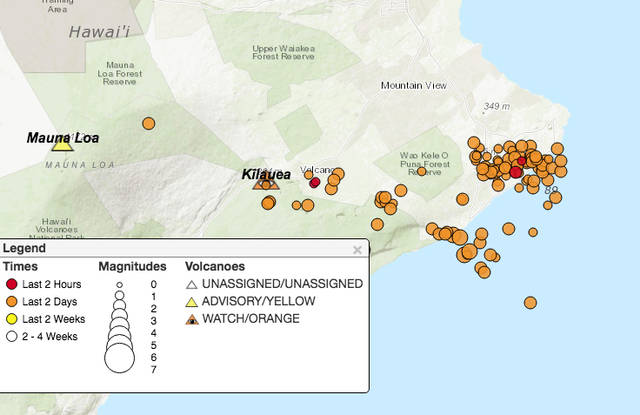

Adding to the chaos, the island’s largest earthquake in more than 40 years, a magnitude-6.9, struck near the south part of the volcano, following a smaller quake that rattled the same area.

Officials said highways, buildings and utility lines were not damaged, but residents said they felt strong shaking and more stress as they dealt with the dual environmental phenomena.

Communities in the mostly rural Puna district, which sits on Kilauea’s eastern flank, know it is one of the world’s most active volcanoes and have seen its destruction before.

Julie Woolsey evacuated her home late Thursday as a volcanic vent, or an opening in the Earth’s surface where lava emerges, sprouted up on her street in the Leilani Estates neighborhood.

Lava was about 1,000 yards from her home, which Woolsey built on a lot purchased for $35,000 11 years ago after living on Maui became too expensive.

“We knew we were building on an active volcano,” she said, but added that she thought the danger from lava was a remote possibility.

She said she thought it was remote even days ago when she began packing and preparing to evacuate.

“You can’t really predict what Pele is going to do,” Woolsey said, referring to the Hawaiian volcano goddess. “It’s hard to keep up. We’re hoping our house doesn’t burn down.”

She let her chickens loose, loaded her dogs into her truck and evacuated with her daughter and grandson. She’s staying at a cabin with her daughter’s in-laws.

Two new volcanic vents, from which lava is spurting, developed Friday, bringing the number formed to five.

Scientists were processing data from the earthquakes to see if they were affecting the eruption, Hawaiian Volcano Observatory spokeswoman Janet Babb said.

“The magma moving down the rift zones, it causes stress on the south flank of the volcano,” she said. “We’re just getting a series of earthquakes.”

State Sen. Russell Ruderman said he’s experienced many earthquakes, but the magnitude-5.4 temblor that hit first “scared the heck out of me.” Merchandise fell off the shelves in a natural food store he owns.

When the larger quake followed, he said he felt strong shaking in Hilo, the island’s largest city that is roughly 45 minutes from the rural Puna area.

“We’re all rattled right now,” he said. “It’s one thing after another. It’s feeling kind of stressful out here.”

State officials didn’t report damage to roadways. Hawaii County Acting Mayor Wil Okabe said the larger quake cracked a beam in a county gymnasium in Hilo, forcing workers to be sent home.

Hawaii Electric Light said the jolt knocked out power to about 14,400 customers, but electricity was restored about two hours later.

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park evacuated all visitors and non-emergency staff. The quakes triggered rock slides on park trails and crater walls. Narrow fissures appeared on the ground at a building overlooking the crater at Kilauea’s summit.

The University of Hawaii at Hilo and Hawaii Community College both closed campuses to allow students and employees to “attend to personal business and priorities.”

Authorities already had closed a long stretch of Highway 130, one of the main arteries through Puna, because of the threat of sulfuric gas.

At Leilani Estates, where lava was pushing through cracks in the earth, some residents still wanted to get home.

Brad Stanfill said the lava was more than 3 miles (5 kilometers) from his house but he was not allowed in because of a mandatory evacuation order. He was frustrated because he wanted to feed his rabbits and dogs and check on his property.

One woman angrily told police guarding Leilani Estates that she was going in and they couldn’t arrest her. She stormed past police unopposed.

Leilani Estates has about 1,700 residents and 770 homes. A nearby neighborhood, Lanipuna Gardens, which has a few dozen people, also has been evacuated.

Kilauea has been continuously erupting since 1983 and is one of five volcanoes that make up the Big Island. Activity picked up earlier this week, indicating a possible new lava outbreak.

The crater floor began to collapse Monday, triggering earthquakes and pushing the lava into new underground chambers. The collapse caused magma to push more than 10 miles (16 kilometers) downslope toward the populated southeast coastline.

Residents have faced lava threats before.

In 2014, lava burned a house and destroyed a cemetery near the town of Pahoa. Residents were worried it would cover the town’s main road and cut off the community from the rest of the island, but the molten rock stalled.

From 1990 through 1991, lava slowly overtook the town of Kalapana, burning homes and covering roads and gardens.

Kilauea hasn’t been the kind of volcano that shoots lava from its summit into the sky, causing widespread destruction. It tends to ooze lava from fissures in its sides, which often gives residents at least a few hours’ warning before it reaches their property.

———

Associated Press writers Jennifer Sinco Kelleher, Audrey McAvoy and Sophia Yan in Honolulu, Mark Thiessen in Anchorage, Alaska, and Alina Hartounian in Phoenix contributed to this report.