The 2018 legislative session is coming to a close with the final day of the legislative session being Thursday May 3, or “sine die.”

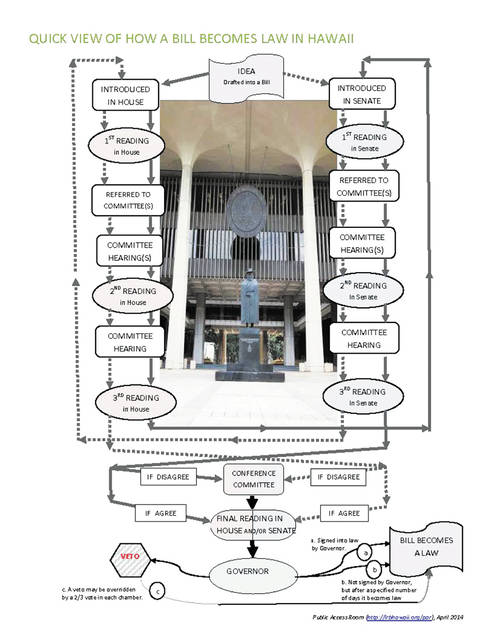

Most of the thousands of bills that started the process in January are by now already dead, having never been scheduled for a hearing, and or being heard and then deferred into oblivion. Those measures that remain alive have two paths open to them: (1) the House or Senate can “Agree” to a particular draft, put an end to further discussions and amendments, have final votes on the floor and send the approved bill to the governor for approval or veto, or (2) the House or Senate can “Disagree” and force the bill into what is called a Conference Committee, for further discussion and possible amendment, or to simply die a quiet death in the backrooms of the Capitol.

At the risk of increasing the readers cynicism and distaste for politics and the political lawmaking process, my thought is that a dose of reality is in order.

Any time a bill is passed into law, someone’s ox is gored. There is always some stakeholder, some interest group, or some individual constituent who does not like the bill and wants it killed.

Consequently, these next 20 days represent the final home stretch when attempts are made to kill various bills, while advocates scramble to protect those same measures and get them passed into law.

Of course, legislators who are working on behalf of those interests groups seeking to kill the various measures also face repercussions if they are “found out” and it is discovered that they are responsible for killing a bill that so many have worked so hard to pass. Needless to say the process is fraught with political land mines and as a result there is endless creativity in the manner in which something is killed, and the degree of stealth and denial of the legislative assassin.

Here is a brief list of common ways a legislator might attempt to kill a bill and come out smelling like a rose, or at the minimum with plausible deniability.

1) The Poison Pill — The introduction of amendments framed as “strengthening the bill” but in effect will make the measure unpalatable to the greater majority, and thus cause the bill to die. In this case, the legislator can/will claim that they were a champion and only trying to support the cause, but in reality they were sabotaging the bill and attempting to gain favor with both opponents and advocates.

2) The Floor Fallacy — A commitment to vote in support of a measure “if it gets to the floor.” The unvarnished truth is that 95 percent of bills that get to the floor will pass. The support that is needed from legislators is help in “getting it to the floor,” as once it does get there almost everyone will vote in support. Many legislators will beg off with the rationale that “I’m not on the committee…” however each has a voice and each can speak out on the issue, lobby the committee chair, it’s members, and leadership of the body.

3) Conference Committee — Conference Committee is the final legislative destination where bills that successfully navigate all the other committees in both the House and the Senate often end up. This “joint House/Senate committee” is where the “differences” between the “House and Senate versions” are supposed to be resolved.

ALL OF THE SERIOUS DISCUSSION THAT OCCURS IN CONFERENCE COMMITTEE IS DONE IN PRIVATE, BEHIND CLOSED DOORS.

• Because the discussions in Conference Committee are done behind closed doors, it is impossible to determine responsibility for any negative outcome.

• Any of the “Chairs” on either side (of which their could be three or four on each side (House/Senate), can block the process simply by not signing a hearing notice, thus not allowing a hearing to be scheduled.

• The “Poison Pill” strategy is often used here so those desiring to kill the measure can claim the high moral ground when they know perfectly well the opposing side will not accept the changes.

• There is no obligation by rule that the two sides must reach agreement, so either side can just continue to find areas to “disagree” and thus never reach a conclusion.

• Either the House or Senate leadership can simply refuse to appoint members to the conference committee, their position being “take it or leave it”.

• No public testimony is allowed. However, for those that have open lines of communications with the legislators, there are private and back door channels.

The rules of the House/Senate indicate “Chairs shall provide 24 hours public notice for the first meeting of the Conference Committee…”. Once the first meeting is scheduled, “public notice” might be a little as a few hours or even less for subsequent meetings. This process effectively prohibits 1/2 of the state’s population who reside outside of Honolulu from participating in any meaningful way, as even a witness to the process and in my opinion, is unconstitutional.

Legal Note: The Hawaii State Constitution – Article 3, Section 12 states in part:

“Every meeting of a committee in either house or of a committee comprised of a member or members from both houses held for the purpose of making decision on matters referred to the committee shall be open to the public.” Obviously a process that gives only 24 hours notice and allows private meetings between legislators to discuss “decision making on matters referred to their committee” does not meet this provision of the Hawai’i State Constitution.

•••

Gary Hooser formerly served in the state Senate, where he was majority leader. He also served for eight years on the Kauai County Council and was former director of the state Office of Environmental Quality Control. He serves presently in a volunteer capacity as board president of the Hawaii Alliance for Progressive Action (HAPA) and is executive director of the Pono Hawaii Initiative.