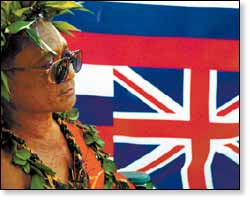

John Butch Kekahu III, Native Hawaiian rights activist and founder of Aloha March events in Washington, D.C., died Thursday in Lihu’e. He was 57. His ideas, ideals, plans and dreams are already living on in some of the people who

John Butch Kekahu III, Native Hawaiian rights activist and founder of Aloha March events in Washington, D.C., died Thursday in Lihu’e. He was 57.

His ideas, ideals, plans and dreams are already living on in some of the people who walked with him and followed him along his journey, said Joan Britton, Kekahu’s partner for 16 years.

“There’s a bunch of people who are going to carry on his work,” said Britton, who was with Kekahu Thursday.

Riley Cardwell, who joined forces with Kekahu around the time of the second Aloha March last year, will take over some of Kekahu’s work. And Mahealani Silva, Ka’iualani Edens, Healani Waiwaiole and others, including his daughter Ruby, are already planning a fund-raiser and other irons Kekahu had in the fire.

“He organized things as much as he could, because he knew he was going,” said Britton.

Kekahu took a different route toward his goal of a reinstated Hawaiian kingdom – a kinder, gentler way that sought to include all races in the islands as allies for the cause, his supporters said.

More than the reinstated kingdom, though, he wanted injustices corrected, and was willing to spend time in jail as part of his nonviolent protest, according to admirers.

“He was a little softer in his approach,” Britton said.

Born in Hanapepe, Kekahu spent part of his life in the Los Angeles, Calif. area, working as a singer, musician and entertainer during the 1960s.

Returning to Kaua’i in 1971, he spent most of the rest of his life fighting for land rights, homestead issues, health care, sovereignty and self-determination.

Founder of the Koani Foundation, an Anahola-based Native Hawaiian rights organization, he was jailed in 1993 for his six-year occupation of Hawaiian Home Lands property there.

Despite a lack of formal education, he lectured on Native Hawaiian self-determination before Congress and federal agencies, and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Cardwell recalled that even after diabetes and other health problems began to sap Kekahu’s health and strength, he continued to fight.

“It is with great sadness that I have seen too many of my people die while waiting for our lands to be returned,” Kekahu once said. “We will resist to our last breath any attempt to perpetuate the wrongs that have been done to us. As a people, we will not vanish into the sunset.”

“My son touched so many lives,” said Rebecca Mikala Kekahu, his mother. “He was indeed a patriot of our people.”

Britton mentioned “committed” when asked to describe Kekahu in one word, while “tireless” comes to the minds of other people.

Known nearly as much for his singing voice as for his activism, Kekahu had plans to launch a spiritual music ministry, to spread his chosen Christianity on the mainland. Even after he got sick, the voice remained amazing, Britton said.

Besides his mother, Kekahu is survived by brother Kawika, sisters Rowena and Rhoda, daughters Ruby and Merlene, and sons John, Aaron, Charles and Danny, and extended family.

Memorial services won’t be held until after the new year, as some family members will not be able to get to the island until late next week, Britton said.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Koani Foundation, P.O. Box 510-182, Kealia, HI 96751.

Staff Writer Paul C. Curtis can be reached at mailto:pcurtis@pulitzer.net or 245-3681 (ext. 224).