As an archeologist, historian and instructor at Kaua’i Community College for many years, Dr. Pill Kikuchi has enthralled generations of students with his research on Hawaiian fishponds. His work, which goes back to the 1970s, has allowed people to understand

As an archeologist, historian and instructor at Kaua’i Community College for many years, Dr. Pill Kikuchi has enthralled generations of students with his research on Hawaiian fishponds.

His work, which goes back to the 1970s, has allowed people to understand ancient Hawai’i.

Hawai’i fishponds were essential to ancient Hawaiians, as fish was a significant source of protein.

Kikuchi’s research had the same impact on up to 150 residents who attended his lecture on Hawaiian fishponds at the Aloha Beach Resort in Wailua last Thursday.

At the event co-sponsored by the Kaua’i Historical Society, Kikuchi spoke about the origins of the fishponds, the political influence the ali’i or the konohiki (land manager) held by controlling the use of the fishponds and the future of fishponds.

Fishponds first appeared in Hawai’i a thousand years ago. But with westernization of Hawai’i, the importance of fishponds diminished in modern times, Kikuchi said.

But the fishponds have a future if they can be reused again, possibly to support the aquaculture industry of Hawai’i today, Kikuchi said.

Today, 480 known fishponds have been identified statewide, with 46 found on Kaua’i. But that total will likely balloon as more fishponds are found among taro patches statewide, Kikuchi predicted.

The development of fishponds reflected the inventiveness and intelligence of Hawaiians, Kikuchi said.

“Inventiveness of the Hawaiians to get food from the ocean was fantastic,” Kikuchi said. “The more I work on this, the more I am impressed with native intelligence. They were really smart people.”

Kikuchi said there exists today much information on the background of fishponds and religious uses tied to them.

For his research, Kikuchi decided to take a different tact: the chronology of fishponds.

Some evidence suggests Polynesians arrived in Hawai’i as far back as 4,000 B.C.

However, other evidence, which is supported by other scientists who have worked on the subject and with him, Kikuchi said, shows Hawai’i was first inhabited by Polynesians at 800 A.D.

Two hundred years later, the first fishponds appeared in Hawai’i, and Hawaiians can take sole credit for it.

There existed no fishponds between Hawai’i and Asia, a distance of 5,000 miles, at that time, and the only fishponds were in China or in the Philippine Islands, Kikuchi said.

Hawaiians, realizing the benefit of having a steady source of protein, put the fishponds everywhere in Hawai’i, Kikuchi said.

The fishponds by the sea, among the largest, were formed on barrier beaches, or in areas where the ocean water dropped off, leaving a sand dune, behind which was “stranded body of water” that became a fishpond, Kikuchi said.

For the ocean variety, Hawaiians built sturdy rock walls to absorb the impact of waves, Kikuchi said. “The seawall was tremendously massive, an ocean equivalent of a heiau,” Kikuchi said.

Construction of the wall involved the use of rocks taken from near the fishpond and the coordination and use of many men, a project that reflected the political power of an ali’i, Kikuchi said.

The leeward sides of the island were the preferred places for ocean-located fishponds because of less wave action.

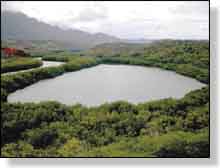

Kaua’i’s two most notable fishponds are the Menehune Fishpond by Nawiliwili harbor, a major visitor attraction, and Nomilu Fishpond, located along the coastline in Kalaheo.

The Menehune Fishpond was built on an existing berm and sits on rocks and a wall of silt, Kikuchi said, and the Nomilu Fishpond is unique because it was built in a volcanic crater.

In building the fishponds, the Hawaiians were credited with two inventions.

One was a sturdy wooden grate built by the entrance to the fishpond and supervised by a kahuna, Kikuchi said. The grate “would stop the fish from leaving, and that is where you would pick your fish out with a long net,” Kikuchi said. On demand, an underling would scoop out fish for the royalty, Kikuchi added.

Another invention was the design and creation of a guardhouse built at the entrance of the fishponds.

Kikuchi said one such structure existed at the entrance to the Menehune Fishpond at one time. Kikuchi noted that he felt privileged to have seen it before it vanished, the victim of time.

Guardhouses were manned by a guard, most likely armed with a spear, to protect against poaching, Kikuchi said.

Kikuchi also said that while the number of fishponds increased, their builders began to wonder about their effectiveness in raising and storing fish, Kikuchi said.

The porous walls allowed fish and water to go in and out of the fishpond, but also allowed in predators, including eel , ulua or barracuda fish, that kept down the yields, Kikuchi said.

Hawaiians tried to find a way to keep predators out, but never found a way, Kikuchi said.

Awa, or milkfish, and mullet were among the favorite fish raised for royalty, and they could not be taken by commoners unless given permission. Those who took without permission were killed, nearly on the spot, Kikuchi said.

Commoners were allowed to take limu, holiholi and other common fish as long as they had permission, Kikuchi said.

As was the case with the use of heiau, the ali’i used the fishpond as a symbol of his power, Kikuchi said.

During certain times of the year, as a way to repopulate ocean mullet, for instance, the ali’i would impose a kapu on catching the fish.

But the same kapu was not applied to the fishpond, allowing the ali’i and the people of his choosing to have unfettered access to the fish, Kikuchi said.

“Fishponds were not considered part of the ocean,” Kikuchi said. “Fishponds were considered agricultural fields in the ocean, and the kapu would not apply to the fishpond.”

Wars were waged among the ali’i for the right to seize and control resources, including the fishpond, Kikuchi said. During war, the ali’i fed his warriors with fish from the ponds, Kikuchi said.

“To show you a good chief, you made sure your boys ate well,” Kikuchi said. Because they knew they could eat regularly, warriors and others sought to attach themselves to a royal court, Kikuchi said.

While men worked in the fishponds, women capable of giving birth were not allowed in them because Hawaiians believed menstrual cycle blood contaminated the fish and fishpond.

Kikuchi also said the estimated yield for Hawaiian fishponds was about 350 to 400 pounds of fish per acre per year.

Those figures wee significantly lower than yields for fishponds run by Chinese and Filipinos at the time.

To build their yields, Chinese, for instance, used non-porous walls for the fishponds, selected certain fish and raise pigs and animals next to the pond, sending waste into the water that helped increase the fish population, Kikuchi said.

The Hawaiians didn’t care about obtaining higher yields if it meant polluting the water , Kikuchi said.

Kikuchi said Hawaiian fishponds had lower yields mainly because of predators and because Hawaiians believed in mo’o, (a lizard or water spirit that protected the quality of water).

“You don’t put human or animal waste or fertilizer into a pond, because that was pollution,” Kikuchi said. “Hawaiians had a thing about ‘you are what you eat.'” So if you got stuff from Hawaiian fishponds… you got fish that was really good quality fish.”

Staff writer Lester Chang can be reached at 245-3681 (ext. 225) and mailto:lchang@pulitzer.net