Kaua‘i woodcarver Robert Hamada is being honored with a showing of his fine woodwork in a show mounted at a leading Honolulu art museum. The show opened on September 17 at the Contemporary Museum at First Hawaiian Center on Bishop

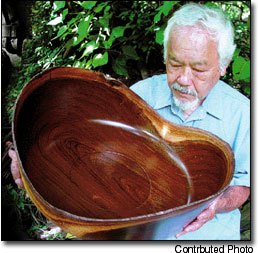

Kaua‘i woodcarver Robert Hamada is being honored with a showing of his fine woodwork in a show mounted at a leading Honolulu art museum.

The show opened on September 17 at the Contemporary Museum at First Hawaiian Center on Bishop Street, and runs through January 25.

Hamada is a life-long resident of Kaua‘i who grew up in the back country of Kapahi, and now lives in a rural home located on a quiet side street in Wailua Houselots.

He learned to be a craftsman from his father who out of necessity, and a flair for creativity, had a home workshop where Hamada learned the basics of woodworking.

Coco Palms Resort employees remember Hamada from his days as a plant engineer at the popular resort.

Today, and over the past decade or so, Hamada has gained an international reputation for his finely-worked wood bowls and other carved pieces of wood art.

To celebrate his show – and his work and life – Pattie Miyashiro has created a printed descriptive catalog of Hamada’s work. Miyashiro’s digital camera work shows off the intricate finishes and wood grain designs that the Wailua Houselots artist brings out by hand.

“His work is three dimensional , unlike paintings that are two dimensional,” Miyashiro says.

“With every turn the bowl changes.”

The writer, and book designer, says she wanted to compliment Hamada’s work by adding stories about the wood pieces and about his life, as well as offering an insight into his artistic soul.

In the book Hamada offers a look at his creative process, a process that begins with the discovery of a distinctive piece of wood somewhere on Kaua‘i. A favorite milo tree from the Pualoke district of Lihu‘e, near Lihue United Church, graces the cover. Hamada says he first noticed the tree in 1938 while attending Kauai High School.

“The tree was toppled over, and over the years had grown sideways,” he recalls. “This is a testimony to the strength and resiliency of the tree how it’s survived the elements. It seems like a tree that could tell you stories, a tree you can depend on.”

Hamada says he looks first at the piece of art that might come out of a particular tree. “Selling the bowl is secondary,” he says.

Hamada says most wood he works with is over 75-100 years old.

“It took a long time for tree to get to that size, and it’s necessary to honor that tree,” he says. “I need to work with the wood and give it the respect its due.”

He is an expert, too, at adding a footing to his finely cut wood bowls, a tricky proposition at best for even the best woodworkers.

“My dad was a carpenter, a blacksmith,” he says.

Another feature is the thinness of the wood in his finished bowl.

“He uses his fingers like a built-in caliper,” Miyashiro says.

“Bob’s pieces are never finished,” she says. “People are baffled by that remark, but in traditional woodworking some kind of varnish is used; the genius of a Hamada piece is that he doesn’t use anything like that, (the finish) always in sanding and polishing. “when you think you’re finished, you’re only halfway there.”

Hours and hours of work go into the sanding of the wood piece.

“Back and forth, three steps ahead, then back two more steps,” Hamada says. “Sometimes I let it rest for weeks or months.”

One of the major influences inHamada’s development as an artist was “Uncle Henry,” a Native Hawaiian medicinal kahuna who was raised in Kalalau Valley on Na Pali.

“The whole village realized modernization was coming in,” Miyashiro says. “Before they left the valley all their priceless spears, they buried and swore not to reveal the location.”

Spears were buried in the valley made out of kauwila wood, a wood which the Native Hawaiians of old considered sacred. Hamada has made a replica of a kahuna staff as a tribute to this legacy.

Letting others, especially young students, know about what’s taken him decades to discover in working wood is another facet of Hamada’s life.

“Bob does his part by passing this information onto other people, making people feel proud they are Hawaiian,” she says. “He tells people to plant trees, like milo, kou, not bring in foreign flowering trees.”

Hamada is passing along his knowledge, and attempting to inspire budding young artists, through presentations in school rooms.

“There’s no such thing as a junk school,” he says. “If you want to do this, do that, there’s no reason you cannot.”

He is also reminding students of the value of education: “Education is a privilege,” he says. ” (You are) sitting here because someone is working two or three jobs (to support you).”

Soon to be released is a DVD that Miyashiro and a creative media team she has put together are producing. The team is using the latest computer technology, both in desktop publishing the book-catalog, and in creating digital video of Hamada.

The DVD is to feature Hamada describing his wood pieces, and footage of him at work.

Chris Cook, Editor, can be reached at mailto:ccook@pulitzer.net or 245-3681 (ext. 227).