LIHU‘E — Co-existing with rare native seabirds that have lived in the Hawaiian Islands long before mankind arrived is something we can easily learn to do without much sacrifice, Earthjustice staff attorney David Henkin said Friday. The population of Hawaiian

LIHU‘E — Co-existing with rare native seabirds that have lived in the Hawaiian Islands long before mankind arrived is something we can easily learn to do without much sacrifice, Earthjustice staff attorney David Henkin said Friday.

The population of Hawaiian Newell’s shearwaters alone has declined some 75 percent since the mid-1990s, largely due to power lines constructed directly in their flight paths, said Dr. Scott Fretz, wildlife program manager for the state Department of Land and Natural Resources.

But the utility company is hardly the only entity responsible. Many others have contributed to the death toll, including the Princeville Resort (now St. Regis) on the North Shore and Vidinha Stadium in Lihu‘e, according to Henkin.

What has really alarmed us are the thousands of birds which have perished in such a short duration of time, Fretz said.

“There are a lot of areas where whole colonies have disappeared,” he said.

When they fly from the mountains to the sea at night, they are “programmed to respond to the moon on the water,” Henkin said.

Because Princeville is located in such a dark quadrant of the island in a “major flyway,” the resort’s bright lights are like a “magnet” to the birds.

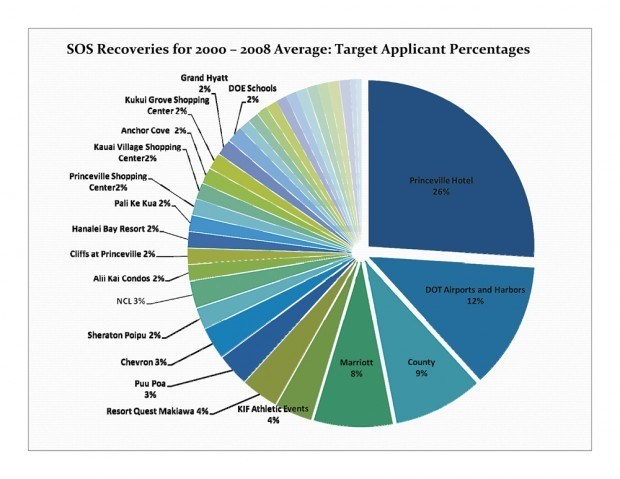

The hotel is accountable for more than a quarter of all light-related seabird takes on island, according to statistics from Save Our Shearwaters.

“We have and have had a seabird protection plan in place for many years,” said St. Regis Princeville Resort General Manager Milton Sgarbi.

With the aid of marine biologist Regi David — who could not be reached for comment after multiple attempts — the resort has maintained conservation efforts, Sgarbi said.

When environmentalists visited the resort immediately following its $100 million renovation and during last year’s seabird fledgling season from October to November — when fall-out is most frequent — the resort had not been doing its part to assist the native birds, Henkin said.

“Extraordinarily bright” lights and pool lights were left on throughout the evening, including when the bird’s are most active a few hours after dusk and between 2 and 3 a.m. when most people are asleep, the attorney said.

In addition, various shades had not been pulled so young birds would not be easily distracted by the resort’s interior lights.

Preliminary statistics found that at least 40 birds were recorded to have been injured or killed mid-way through the 2009 season at the resort, according to Henkin.

Some takes are unavoidable, but there are many proactive measures individuals, businesses and government agencies can take to help remedy the situation which do not require much effort, he said.

Another example would be shielding stadium lights, as Kaua‘i County is responsible for around 13 percent of all light-related deaths and injuries, which includes KIF athletic events at 4 percent.

This minimal action could result in about a 15 to 40 percent reduction in seabird takes at these facilities, Henkin said.

“The best information we have suggests that there are approximately seven documented ‘takes’ at county stadium facilities per year,” county spokesperson Mary Daubert said in an e-mail.

SOS studies documented some 19 birds gathered at various county ball parks and stadiums in 2007 and around 20 in 2006, according to Henkin.

“There may be fewer birds coming down at football games, not because they are doing anything different, but because there are fewer birds,” he said.

Lights are required to be off at all county park facilities by 8 p.m., except during KIF football games, Daubert said.

“The timing of the football season is unfortunate,” Henkin said.

But, there are ways to work around the situation like allowing only authorized users to operate the lights, re-considering the timing of some games and switching lights off as soon as possible.

“Sometimes a power outage may create problems with the timers, and when we become aware that there is a problem Parks resets the timers,” Daubert said.

“There is also a problem with vandalism, and there have been occasions where park users will literally break into the timer system to turn the lights on when they shouldn’t be,” Daubert added. “Again, when reported our Parks staff responds and resets the timers.”

Kaua‘i Island Utility Cooperative isn’t the only entity currently in the process of applying for an Incidental Take License which would authorize 125 Newell’s shearwater mortalities and 55 “non-lethal injuries” annually for the co-op, according to the draft plan. The county is also seeking an incidental take permit which they are “currently preparing an application for coverage under the Kaua‘i Seabird Habitat Conservation Plan,” Daubert said.

DLNR has been contacting landowners across the island “aggressively” for the past two years for enrollment in the HCP which will “hopefully” be completed by 2012, Fretz said.

The HCP would assist entities in reducing the number of seabird takes each year and would help “manage” Hawaiian petrel (‘ua‘u), Newell’s shearwater (a‘o) and band-rumped storm-petrel (‘ake‘ake) populations.

Based on available science, the HCP says the population of Newell’s shearwaters on Kaua‘i is declining at a rate of 60 percent every decade.

“We’re putting together a landscape scale recovery project,” Fretz said. “To do this, we’re looking to reduce the impact of lights and power lines and find areas where these birds nest.”

It is “ultimately not the state’s responsibility” to instigate efforts to mitigate takes, Henkin said.

One exception might be smaller enterprises, like mom-and-pop businesses that may need some extra assistance. Taxpayers are paying for what larger entities are required to do by law in the first place.

“It’s time for those big players to stop shirking their responsibility,” Henkin said.