LIHU‘E — A Kaua‘i County Council committee this week unanimously agreed to fund a 10-year lease on a public use helicopter, clearing the way for the Garden Isle to join Hawai‘i’s three other chopper-owning counties. The acquisition, requested by the

LIHU‘E — A Kaua‘i County Council committee this week unanimously agreed to fund a 10-year lease on a public use helicopter, clearing the way for the Garden Isle to join Hawai‘i’s three other chopper-owning counties.

The acquisition, requested by the Kaua‘i Fire Department, seeks to improve public safety by reducing response times and limit exposure to lawsuits by bringing the county into compliance with federal aviation regulations it has long dodged, but could cost an additional $700,000 or more annually.

Daryl Kaneshiro, chair of the Budget and Finance Committee that approved the request Wednesday morning and also moved forward a money bill that would spend $285,000 on the first year of the lease, shot down questions from the community wondering if now is the right time to spend the extra cash.

Kaneshiro said he has personally needed the services of a rescue helicopter on multiple occasions, including being flown out of Waimea Canyon and one instance where he saw a friend get shot. He said every minute waiting for assistance felt like an hour, and “when it comes, it’s a blessing.”

Councilman Dickie Chang said there can be “no price on a life saved.”

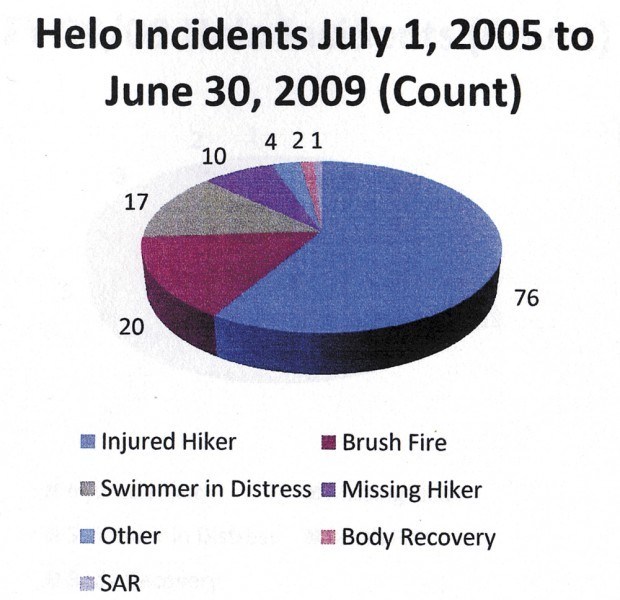

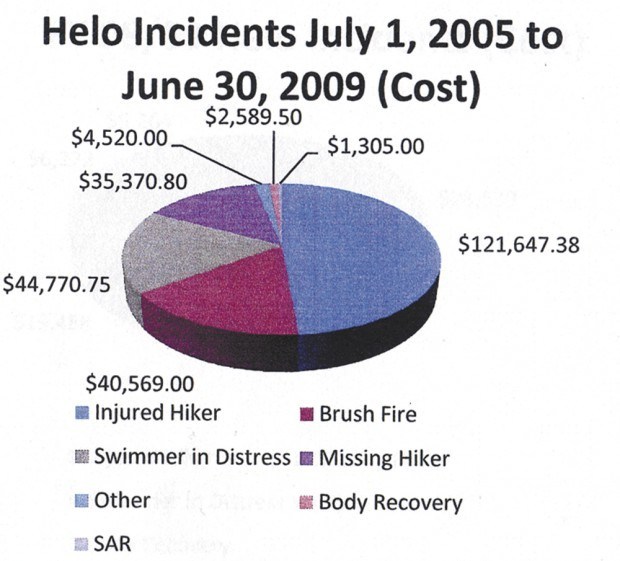

Over the four-year period from July 1, 2005 to June 30, 2009, KFD spent some $250,000 responding to 130 incidents with a helicopter, according to data provided by KFD Chief Robert Westerman to the council. Of those incidents, 66 percent were injured or missing hikers, 15 percent were brush fires and 13 percent were swimmers in distress.

The 10-year lease of an MD530F single-engine helicopter advocated by Westerman would follow the model in use currently on the Big Island.

In addition to the $285,000 annual payment for the loan — one-tenth of the principal and interest on a $2.1 million chopper — Westerman estimated it would cost an additional $238,000 to contract an outside pilot, $78,000 to contract maintenance, $73,000 to fuel the helicopter and nearly $96,000 in “administrative costs,” which he said do not include insurance.

The annual loan payments could end up being considerably less if a Community Development Block Grant or assistance from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security is used to bump up the down payment and cut the cost to the county in half.

The cost of constructing a hangar — estimated at $180,000 — would be a one-time charge amortized over the life of the asset, and the helicopter could be housed at Lihu‘e Airport free of charge through an agreement with the state where the county would agree to continue responding to emergencies on state land.

Council Chair Bill “Kaipo” Asing said the state should kick in additional money because the vast majority of rescue operations take place in either Na Pali Coast State Park along the Kalalau Trail or in Waimea Canyon or Koke‘e State Parks.

At the end of the 10-year lease, the county would own the chopper free and clear. Finance Director Wally Rezentes Jr. said he expects, with proper maintenance, the helicopter will last 15 years or more.

Councilman Tim Bynum described the jump from $50,000 or $75,000 annually to ten times that as “a big chunk of change difference,” to which Westerman responded that it doesn’t come down to the “cost per call” because firefighters are always going to do what it takes to get the job done and need the training to be safe when they’re doing “some of the riskiest stuff we do.”

Kaua‘i County has been skirting for years Federal Aviation Administration rules that bar training on single-engine helicopters that are not devoted to public use for at least 90-day intervals and limit the frequency of rescue operations, a practice that Bynum said would be “irresponsible” if allowed to continue.

“If we haven’t done everything by the book … can we sit in front of the judge?” Westerman asked, referencing the potential liability the county would incur if anything went wrong. He said the county has been under additional scrutiny from the FAA in recent years and said the particularly risky rescue after August’s ultralight crash in Hanapepe convinced him it was finally time for a change.

The money bill will now move to the full council, while the other costs will be added to the county’s 2010-2011 fiscal budget. Westerman told the council and confirmed to The Garden Island that the department will not be cutting elsewhere in its budget.

Charging for rescues

In 1995, the Kaua‘i County Council passed an ordinance authorizing county departments to ask the Office of the County Attorney to issue claims against those whose “gross negligence” led to situations that required costly rescue operations.

“Gross negligence” is defined in the ordinance as “conduct which is either intentional or committed under circumstances exhibiting a reckless disregard for the safety of oneself or of others.”

County spokeswoman Mary Daubert said last week the county has never cited anyone who were rescued because they exhibited gross negligence, but The Garden Island has in its archives a June 2000 story stating the county was prepared to pursue legal action to recover rescue costs after three men plunged from Wailua Falls — two of them deliberately.

“Such blatant disregard for their personal safety and the safety of our rescue crews should not and will not be tolerated,” then-Mayor Maryanne Kusaka said at the time.

“In concept I believe that we should consider charging in cases of ‘gross negligence,’ however, the challenge is in how to set that bar and how to apply charges fairly and consistently depending on the circumstances,” current Kaua‘i Mayor Bernard Carvalho Jr. said in an e-mail from Daubert this week. “This will take some discussion between the Kaua‘i Fire Department, our attorneys and others, to determine how best to implement this law.”

Westerman said in his communication to the council that “perception to the public” is one of many reasons to not pursue the recovery of expenses, saying the implementation of similar policies in other locales has hurt the tourism industry.

He also said locals and visitors alike would be less likely to call for help if they think they might be charged for the rescue, potentially creating “a more dangerous situation where they try to self-extricate or call on friends who then too become victims.”

County Attorney Al Castillo said during a brief recess during Wednesday’s council meeting that a potential impact on tourism would not considered when applying the ordinance.

Asking for the keys

Should KFD close the deal and secure its own helicopter, other departments might line up and pay interdepartmental fees for keys to the chopper.

Kaua‘i Police Department Chief Darryl Perry told the council Wednesday that a helicopter could be used from a law enforcement perspective when officers are in “hot pursuit” of a suspect and in egregious situations where a helicopter could help end a high-speed chase.

He said it could also help find missing persons, locate stolen vehicles, and assist with marijuana eradication in between scheduled “green harvest” raids if KPD receives a tip, noting a helicopter would be “very valuable” as it would be “good to have … if you need it in a moment’s notice.”

A spotlight and forward-looking infrared camera to sense body heat could keep the public safe and a video camera to capture footage of criminal proceedings like the protests against Hawai‘i Superferry in Nawiliwili could lead to more convictions, Perry said.

One Kilauea resident testified that he hoped the helicopter would patrol the highways, saying drivers might keep safety in mind if they know “big brother is watching,” a reference to the popular George Orwell novel “1984” in which a totalitarian regime surveils citizens in their homes and executes those who exhibit independent thought patterns.

Westerman told the council the helicopter could also be used by the Departments of Public Works and Planning “to fly over areas requiring visual confirmation or photographs of boundaries permit violations, grading violations, dams or other illegal activities … with the caveat that emergency needs of public safety, fire and police preempt any other flight operations.”