Scientist urges site-specific warnings to save more lives LIHU‘E — A local scientist has boiled a decade of personal research into an academic study on Kaua‘i drownings, which have doubled over the years despite better precautions and more lifeguards. Dr.

Scientist urges site-specific warnings to save more lives

LIHU‘E — A local scientist has boiled a decade of personal research into an academic study on Kaua‘i drownings, which have doubled over the years despite better precautions and more lifeguards.

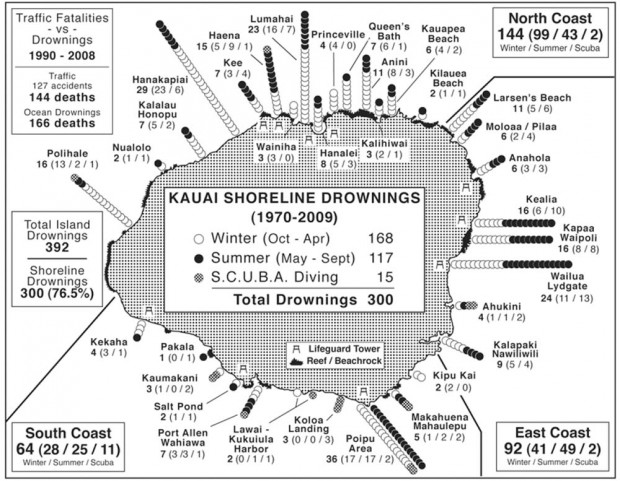

Dr. Charles Blay, a geologist, naturalist and educator at TEOK Investigations in Po‘ipu, said more than 300 drownings have occurred on Kaua‘i over four decades, not to mention all the unreported near-drownings. He attributes a high ratio of visitor deaths — three-fourths, with the average age 46.2 and 85 percent male — to a lack of foreknowledge on specific beach hazards.

“When the waves, currents and shoreline features vary so much, it makes no sense to use generic approaches, like standard warning signs in a water safety program,” Blay said in a recent interview.

Lifeguards at all beach locations is not practical, he said.

“I suggest placing effectively informative signage at each accessible locality, perhaps emphasizing that numerous people have drowned at the locality in question and what has been the principal hazard for which they should be aware,” Blay said.

The preferred approach to drowning prevention information should ultimately be available for people in the travel information they browse when researching their trips, he added, or to inform tourists while en route to Kaua‘i on the plane and at the hotels with videos and published materials on specific water hazards.

Blay also advocates placing information kiosks at several locations to describe known water hazards and how to react in different situations. The kiosk would include historical and cultural information about the beach, along with maps plotting the water hazards with details of past drownings.

“Information transfer from those who know to those who do not is the critical element here,” he said. “Site specific information placed at points of contact would be a great start, instead of generic warning signs.”

Blay’s paper, “Drowning Deaths in the Nearshore Marine Waters of Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i 1970-2009,” was published in the August issue of a peer-review publication called “International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education.”

Blay said he wanted a scientific approach to water safety on Kaua‘i, and expects the research to generate interest in more studies.

“Hopefully, someone will take this and make their own conclusions and I hope there is enough data there to do that,” he said.

The ‘Drowning Chain’

The “Drowning Chain: Ignorance, disregard, or misjudgment of danger; uninformed or unrestricted access to the hazard; lack of supervision or surveillance; and inability to cope,” are four criteria developed by Shaun Whatling as the cause of aquatic injury or death.

To break links in the drowning chain and save more lives, Kaua‘i lifeguards now number around 45 at 10 locations, with floatation devices and information on saving a drowning victim now at 100 locations.

Blay credits the lifeguards with saving many lives, but said preparing visitors before they set foot on the island or the beach will help remove the ignorance factor.

As a volcanic island in the north central Pacific Ocean, Blay notes that Kaua‘i has a unique variability of physiographic settings and waves. The most common pocket beaches have energetic wave conditions, while the milder Westside strandline beaches also have variable wave conditions.

Na Pali Coast on the North Shore makes a rescue difficult with its steep cliffs; powerful waves during the winter months have washed away people walking on the shoreline. The reef platforms are close to shore and people walk on them and sometimes get caught in channels of powerful seaward currents.

The report illustrates how a generic approach to water safety does not address site specific dangers. Examples include different types of locations where many drownings occur.

Queen’s Bath is a remote feature of northern Kaua‘i, touted in guidebooks as a destination of special beauty. During the winter months, when wave activity is fierce, people have drowned for not anticipating the danger of getting washed out near the shoreline.

In contrast, Po‘ipu Beach in the south is world famous for its sandy beaches and gentler slopes. It has the largest concentration of lifeguards along a resort-saturated coastline. Yet, the sheer numbers of people involved in various water activities has given Po‘ipu Beach the highest increase of drownings, according to Blay.

Documenting more than 500 incidents on nearshore marine drownings, along with inland lakes, rivers and swimming pools, Blay said there are also occurrences of people wandering on to private land and drowning in the turbulent undertow of inland waterfalls.

History of water safety

Blay presents a history that begins in the 1970s, when the Committee on Water Safety was formed in response to a series of tragedies. Lawsuits and legislation helped to distinguish county from state liability for injuries and deaths and the generic hazard signage began.

The 1980s brought the Kaua‘i Ocean Rescue Council and Kaua‘i Water Safety Task Force to promote boating and water safety. The report notes that more columns and prevention information began to appear in guides to Kaua‘i beaches.

Blay describes the 1990s as “a decade of action” for water safety, in part as legal protection that changed the dynamics of state and county responsibilities with public and private beaches. In 1996 the state passed a law requiring signage for specific natural conditions including shore breaks and strong currents.

During this time, Blay notes that Mayor Maryanne Kusaka requested the Kaua‘i Water Safety Task Force to improve the water safety program, which resulted in the expansion of lifeguard-protected beaches, using personal watercraft and other new technologies in their lifesaving efforts.

The Kaua‘i Fire Department established the Ocean Safety Bureau, and the Junior Lifeguard Program began.

Still, by the end of the decade, Blay noted the number of drowning deaths climbed to record levels. Periods of lower drowning numbers were attributed to a plunge in tourism following the hurricanes.

After 2000 the Internet ushered in an era of online safety when former firefighter Winston Welborn began to add tips along with his surf conditions report on kauaiexplorer.com. The Hawaiian Lifeguard Association also went online at aloha.com/~lifeguards, as did the UH School of Earth Science and Technology at oceansafety.soest.hawaii.edu.

About this time Pat Durkin designed WAVE — Water Awareness Visitor Education — with materials aimed at the tourism industry. Blay said it was the first effort to include information of visitor deaths and injuries.

These separate efforts have not had the overall intended impact they would like to achieve, Blay said, adding that these prevention efforts should come together in a more concerted effort.

Blay will discuss the unique reef system of Hawai‘i at a Sept. 1 presentation at the Hanapepe Library. He can be reached at 808-742-8305 or email teok@aloha.net.

• Tom LaVenture, staff writer, can be reached at 245-3681 (ext. 224) or tlaventure@ thegardenisland.com.