A rapidly-spreading coral disease along Kaua‘i’s North Shore may be affecting turtles, fish and even humans, according to a team of scientists. A year ago, Dr. Greta Aeby, a coral expert with the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology at the

A rapidly-spreading coral disease along Kaua‘i’s North Shore may be affecting turtles, fish and even humans, according to a team of scientists.

A year ago, Dr. Greta Aeby, a coral expert with the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology at the University of Hawai‘i, sent out an alert to scientists and divers about a disease affecting corals in Kane‘ohe Bay on O‘ahu.

When Terry Lilley, a marine biologist and scuba diver in Hanalei, received the alert, he said he became concerned because it sounded similar to what he had seen and filmed — but could not identify — in reefs on Kaua‘i.

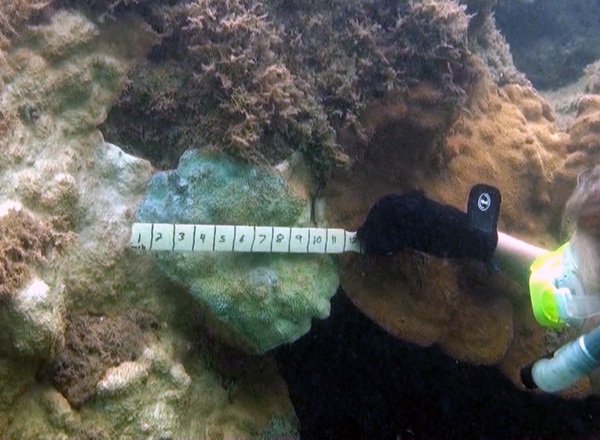

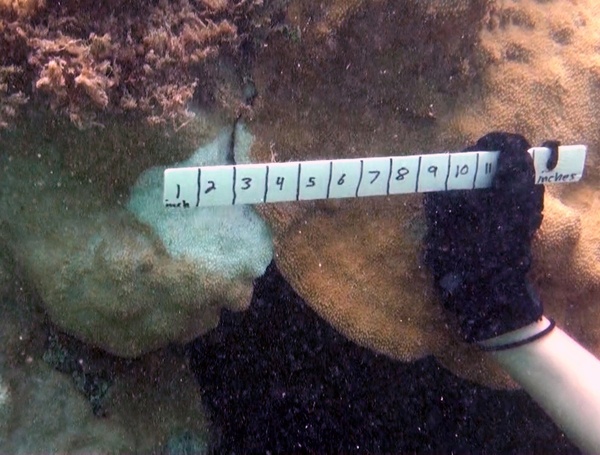

As it turns out, the disease is similar to that seen on O‘ahu, which is eating the coral at lightning speeds, according to Lilley, who graduated with a degree in biological sciences from California Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo, in 1980. As the black-colored bacteria moves through the coral, it strips off live tissue, leaving a white, dead skeleton exposed.

“The fascinating part is this disease has gone out of control and could potentially wipe out the reefs,” he said. “We don’t know where this bacteria came from. We don’t know how it spreads.”

A year ago, Lilley began filming infected rice corals along the North Shore. At that time he said he documented 100 infections at 20 different dive locations. Today, he said the number of infected coral is likely in the millions.

“Last summer, for some unknown reason, the infection rates went up to 100 infections per dive, to where now, at a number of sites, there are so many infections we are counting the corals that are not infected,” he said. “Every place along the North Shore we are finding this stuff, and a lot of it.”

‘Stumped’

After reviewing older underwater video footage he shot along Kaua‘i’s North Shore, Lilley tracked the disease back to 2007, which he said is important for giving scientists a timeline.

The white coral disease outbreak is believed to be caused by a new strain of cyanobacteria, unique to Kaua‘i, which is killing corals that often take 50 years to grow at a rate of one to two inches per week, according to Lilley.

“There seems to be an unknown fungus working with this bacteria … in my career as an investigative biologist, I have never been stumped to a degree such as this.”

Over the past few months, a rapid response team of top scientists — including Aeby and Dr. Thierry Work, head of Infectious Disease for the U.S. Geological Survey — have been involved in a disease study along Kaua‘i’s North Shore.

In August, Work traveled to Kaua‘i and did extensive DNA and toxicology testing on the disease at Tunnels Reef. An official report was filed Sept. 4 by the USGS outlining the reef’s poor condition.

“Because of the extensive mortality evident from Mr. Lilley’s photos, we (USGS) decided to carry out a field investigation to sample corals in attempts to figure out what may be causing this mortality,” Work writes in the report. “The overall picture was one of a severely degraded reef impacted by sediments and turf algae. … It is tempting to conclude that degraded conditions of the reef could have precipitated infection by fungi and cyanobacteria leading to the lesions seen here, however, confirming this would require longitudinal studies and more systematic sampling over time.”

Work returned to Kaua‘i in early October to perform a second round of detailed testing.

“They not only did DNA testing but they took samples of this fungus for toxicology studies and they took samples of the water column, to see if this disease is actually floating around in the water,” Lilley said.

A full report of Work’s DNA, bacteria and toxicology study is expected to be available within the next month or so.

Marine life,

people affected

At this point, Lilley says the disease outbreak is no longer just his own opinion, which he admits has been called into question in the past, but a “mathematical equation.”

“This needs everyone’s attention,” he said. “If we lose our coral reefs on Kaua‘i, it’s not only going to affect the marine life … it’s going to affect you and I.”

After confirming the disease in early October, Aeby and her team began treating infected corals in ‘Anini Bay with a type of marine epoxy, similar to a fire break approach, in an attempt to try and stop its spread.

“It is working,” Lilley said. “Most of the epoxy barriers we put down did stop the disease from spreading across the coral … that’s the good news.”

But the problem along the North Shore is that the disease is so widespread, with upwards of 1 million affected coral, according to Lilley.

“This study is more for helping other places, not the North Shore,” he said. “There is no way we can physically stop it at this point.”

Instead, the team of scientists is looking for ways to control the disease should it surface in other locations.

Another big concern is whether this new strain of cyanobacteria could be infectious to humans and marine life.

“I believe it is already affecting marine life,” said Lilley, who claims to have filmed turtles with large tumors and puffer fish with fins that are rotting and falling off.

The question of whether there is a connection between the dying coral and diseased marine life is still to be determined by Aeby, Work and other scientists involved in the ongoing study.

While Aeby and Work continue to search for a cause and cure, Lilley is monitoring and documenting its spread with underwater video equipment.

The biggest setback of the ongoing study, according to Lilley, has been financial insufficiency.

“Most third-world countries that I’ve been in communication with, including the Cook Islands — we’re talking about places that aren’t wealthy — put 1,000 times more resources into studying their marine environment than Kaua‘i,” he said. “I’ve been all around the world and I’ve never seen any island that is more understudied than Kaua‘i.”

Lilley said his concern is not that future generations won’t be able to enjoy Kaua‘i’s coral reefs.

“I’m extremely concerned about whether or not you, on your next trip back to Kaua‘i, 10 years from now, are going to be able to see a coral reef.”