HONOLULU — A diagnostic report released Wednesday by the U.S. Geological Survey says a coral disease outbreak along Kauai’s North Shore is nothing short of an “epidemic.” “Given the scale of the event, the large numbers of corals affected, and

HONOLULU — A diagnostic report released Wednesday by the U.S. Geological Survey says a coral disease outbreak along Kauai’s North Shore is nothing short of an “epidemic.”

“Given the scale of the event, the large numbers of corals affected, and the consistent preponderance of a few agents (cyanobacteria and fungi) associated with gross lesions that look similar in both Makua (Tunnels Beach) and ‘Anini, this outbreak would have to qualify as an epidemic,” Dr. Thierry Work, head of Infectious Disease for USGS, writes in the report.

Work says this is the first time a cyanobacterial/fungal disease on this scale has been documented in Hawaiian corals and that he feels “very comfortable” describing the situation as he sees it.

“I wrote (epidemic) down in there because it’s true,” he said Wednesday, shortly after releasing his report. “The bottom line is the definition of an epidemic is an unusual or above-background occurrence of a disease. It doesn’t necessarily need to be a lot of animals.”

Work went on to say that reefs along Kaua‘i’s North Shore look “horrible” and that locating diseased corals at Tunnels and ‘Anini was not a difficult task.

“I have never seen a cyanobacterial disease like this killing corals to this degree in Hawai‘i,” he said. “This is truly an unusual event.”

North Shore tests

In August, Work traveled to Kaua‘i to complete tests on the diseased coral at Tunnels reef. An official report was filed Sept. 4 outlining the reef’s poor condition.

“The overall picture was one of a severely degraded reef impacted by sediments and turf algae,” Work wrote in the September report.

In late-September, Work — along with Dr. Greta Aeby, a coral expert with the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology at the University of Hawai‘i, and Amanda Shore, a UH graduate student — accompanied Terry Lilley, a biologist and Eyes of the Reef volunteer who first alerted scientists of the unusual outbreak, to ‘Anini to photo document lesions, sample coral and apply a marine epoxy to affected corals to try and stop the disease’s progression.

At that time, paired normal and lesion tissues were collected from 15 different coral colonies. Work’s findings were outlined in Wednesday’s report.

“Live coral cover appeared unusually low as compared to what would be expected on a healthy reef,” he wrote. “On microscopy, of the 17 samples with lesions, 10 had tissue death (necrosis) associated with cyanobacteria, five had necrosis with cyanobacteria and fungi, and the remainder had no recognizable microscopic lesions.”

As for non-lesion coral samples, microscopic changes in tissue suggests the animals are undergoing some type of stress, according to the report.

“Based on the large percentage (59 percent) of corals affected by cyanobacteria only at ‘Anini, I suspect this organism is playing a primary role in causing lesions, with the likelihood that fungi may pose a complicating factor,” Work writes. “In aggregate, 88 percent of corals with lesions at ‘Anini are infected with cyanobacteria and fungi.”

The reefs at both ‘Anini and Tunnels are heavily overgrown by turf algae, have low coral cover and large amounts of suspended solids in the water column, according to Work. And while sedimentation and the presence of the disease appear closely associated, Work says that remains to be proven through further scientific testing.

“That said, the similarity of the findings at Makua (Tunnels) and ‘Anini strongly suggests a common underlying cause, and it is difficult to conclude that the degraded environmental conditions at both sites are not, in some way, driving the occurrence of these infectious diseases on corals,” Work writes.

What’s next?

As a scientist, Work says his job is simply to provide data on his findings. After that, he says it is up to decision-makers and the community to decide what they want to do about it.

The next step of his work will be to determine the disease’s cause.

“Is it coming from Hanalei River? Is it coming from Hanalei Stream?,” Work questioned. “The first question is where is the source.”

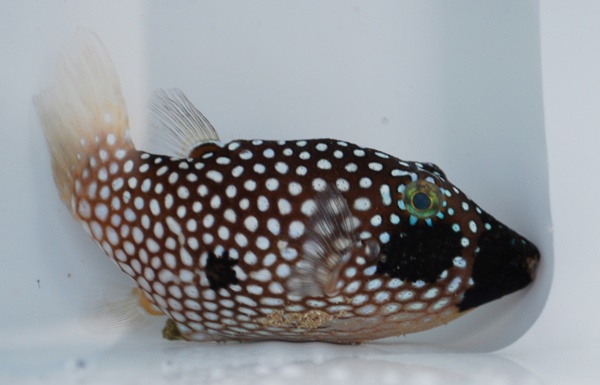

Another big concern is whether this new strain of cyanobacteria is infectious to humans and marine life. Work says he and other scientists involved in the ongoing study have spotted puffer fish with skin discoloration and unusual lesions on their fins.

“Right now I have no evidence that there’s any relationship between the coral disease and what’s happening to the turtles and fish,” Work said. “We’re going to try to come out next week to look at the fish, to see what’s causing the lesions.”

The bottom line, according to Work, is that Kaua‘i’s reefs are heavily degraded and infected with a rapidly-spreading white coral disease unlike any seen here before. How they got this way is yet to be determined by Work, Aeby and other scientists.

“I think people need to know what’s going on with their reefs,” Work said. “It’s actually quite serious.”

• Chris D’Angelo, lifestyle writer, can be reached at 245-3681 (ext. 241) or lifestyle@thegardenisland.com.