Bill Fernandez: Talk Story

Growing up in Kapa‘a, Bill Fernandez wanted to be a fisherman.

He tells stories of free diving, spearing fish and leaving a trail of blood in the water. And that, of course, attracted predators.

“The reef shark will come, and sometimes, you get into one of these tigers. Those guys are vicious,” he said. “Fortunately, I’m still here. After that shark makes some passes by you, you do get a little concerned. Get out of the water as fast as you can.”

Fernandez laughs and smiles as he continues sharing his memories.

“The rule of thumb is, don’t feed them. Once they get fed, they’re pretty hard to stop.”

He never feared the water.

As a boy, he delivered cigarettes to machine gun nests not far from his home today during World War II. He shined shoes. He rolled dice. He survived.

“I like to say when I was born, I had one foot in Christianity, and one foot in the old Kahuna system. My mother was raised in the old Hawaiian way. She still believed in those things, although we went to church every Sunday.”

His goal, up to his 18th birthday, was to fish the water off Kaua‘i and eventually, retire.

Well, the retirement part worked out.

Career-wise, not so much.

Fernandez did more than perhaps even he imagined.

“Times change,” he said. “You get motivated.”

Absolutely.

Consider these accomplishments of Bill Fernandez:

• Graduate of Kamehameha School in Honolulu

• Graduate of Stanford

University

• Attorney for 15 years in California

• Served as a judge in the California Superior Court

• Mayor of Sunnyvale, Calif.

• Author of “Kaua‘i Kids in Peace and War,” and “Rainbows Over Kapa‘a.”

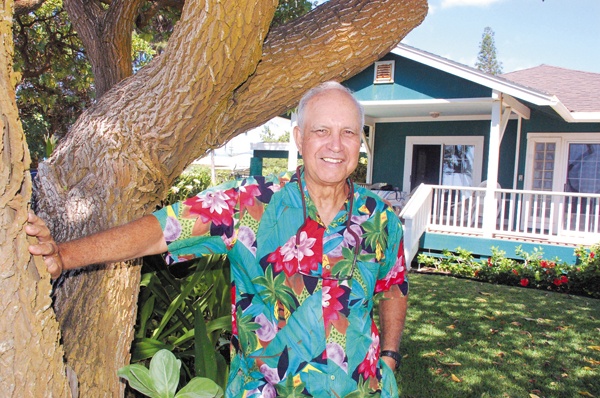

Retired today, Fernandez and his wife Judith live in the same oceanfront home his mother Agnes bought around 1927 with her pineapple earnings, and passed on to her son around 1950. It is a beautiful green house with white trim, and a front porch perfect for entertaining guests or enjoying the view.

“My mother worked in the cannery at the time, it used to be 25 cents a day, she bought this house,” he said.

Since, that home has withstood four tidal waves and four or five hurricanes,” Fernandez said, proudly. “You know the worse thing that ever happened to this house? You see the glass table? It was turned over in

‘Iniki. That’s the only thing that’s ever happened to it.”

“And the glass wasn’t even cracked,” Judith added.

During those storms, debris filled their yard, homes were destroyed, roads disappeared. Yet the Fernandez home stood strong.

“This house has survived all of those disasters, where everything else has fallen down,” he said.

Fernandez paused when asked how it survived.

“It’s got the protection of the Kahuna,” he said. “We kind of think that somehow, it got blessed well, or it’s on sacred ground. Because everything else you see around you is new.”

“Agnes is protecting us,” Judith added.

“That’s why we call this place Agnes’ house.”

Fernandez has indeed led what some might call a charmed life, but it’s not about charm. It’s about hard work, about overcoming obstacles such as asthma, setting goals, self belief and a dream to be part of the world around him.

He wants to encourage others, too, to explore the world, to push beyond their limits, to believe they can achieve their dreams. It’s part of why he wrote those books about growing up on Kaua‘i, a time when some 25,000 people lived here, and how he found his way to Menlo Park, Calif., where he owns a home, and to Sunnyvale, Calif., where he was mayor and created a masterplan of streets, community centers, schools and infrastructure that was so successful it serves as a model city today.

“I wrote this story (“Kaua‘i Kids”) because of my father and mother, poor Hawaiians, how they struggled to finally make it. There’s a lot of background history in it. I wanted to tell about those folks and their hard times.

“This story (“Rainbows Over Kapa‘a”) I wanted to write because I wanted to tell about growing up on an isolated island, and about believing there was more beyond us and I wanted to find it.”

•••

What was it like growing up here?

It was a real time of innocence. You’re living on an isolated island. You don’t know anything about the outside world. You’re living almost in like a fantasy land, where you can’t believe there’s anything else except your particular island.

You also have to make anything you want. When the boat comes in, and it’s very seldom that it comes in, it isn’t bringing stuff for kids. They’re bringing something for the plantation or the canneries or the mom and pop businesses that are in town.

You have to do a lot of hand work and get people to help you out. If you want to make a canoe, you get an old piece of corrugated metal, and you find a way to bend it, shape it, and you go out into this ocean in your little tin canoe and you struggle in the sea.

That was always the struggle with the ocean, this powerful thing, it scared you, but it’s delightful. There’s so many interesting mysteries under that water.

That’s why I loved spearfishing. You always found new little treasures, whether it’s a piece of coral or a forest of what we call black coral that’s growing in the deep. It’s just like having a whole, new fantasy land.

The problem growing up on a small island like this, you hadn’t any broad vision. You didn’t see a bigger picture. Ambition was not part of your life.

There was a plantation that controlled the area. The whole island was like a baron of the rich. There were all the little peons like myself and others being regulated by the plantation.

What motivated you do achieve so much?

There has to be a better life. War World II starts, Pearl Harbor. You suddenly have thousands of soldiers form the Mainland descend upon you. You become aware of history. You become aware that Hitler’s going through Europe and is causing all kinds of trouble. These guys are coming here not only to train to fight, but they have also been living lives that are interesting.

You suddenly realize there is a bigger world than this little cubicle you’ve been living in. You become curious, you want to know. You want to learn. You want to become educated.

That’s why I took the opportunity to go to Kamehameha Schools, to get started learning about the bigger picture.

As my teacher said on my graduation, you came here like a country bumpkin, and you’re going out as a leader.

You’re named after

your father. What was his influence?

My father always said this, and he had only a third-grade education. He really felt if he understood the law, he would have been much more successful than he was. He had a lot of different businesses that turned out to be failures.

The interesting part of the story is that, for him, he had a lot of failures. He built the biggest movie theater in all the islands, 1939, a 1,050 seat Roxy was right behind the ABC store. Everybody said that’s a folly, that’s foolish, and really it was. Come 1941, he can’t pay the bills, he can’t pay his mortgage, the bank is foreclosing. Guess what? Pearl Harbor happens. Martial law is imposed. All civil proceedings stop, so the foreclosure can’t proceed, and now descending on the island is the Rainbow Division out of New York. Twenty-five thousand men finally are here for housing and training. Where are they going to go for entertainment? The movies! I still remember this, Christmas Eve, my dad is talking to my mother in the kitchen, he said we have $50,000 and we have $50,000 in the bank. That’s why I called the story Rainbows over Kapa‘a, because like the Chinese before him who planted rice in the mud of Kapa‘a and made their fortune, he has bought his pot of gold by building the Roxy theater like he did.

What do you think of Kaua‘i today?

It’s much, much better. I tell you, when I was growing up, you lived the plantation life. There were rules and regulations that you had to follow. It’s like unwritten laws that you obeyed. We were a community of elite and of course, the dregs. Among the ethic groups that went out to work the plantations, there was camaraderie. You were friendly. But there was class separation.

The great thing that happened after the war, the sons of the plantation workers got educated and used the GI Bill. They realized as I described earlier that there’s a bigger world out there, that there’s a democracy, that all men are created equal and they began to make change after the war, like in ’46 you had the great strike, where the plantation workers, canneries workers all went out. When the strike was over, the Hawaiian cultural worker became the highest paid in the world, $1.21 an hour, not much, but it shows the disparity.

The great thing about what we have now is equality. You have a great sense of equality now than ever before. That’s the wonder of what’s happened.

Looking back on your career, is there anything you consider your greatest accomplishment?

Well, as a judge one of the most interesting cases that I had was a Down syndrome child that the parents wanted to allow him to die. He needed a life-saving operation for his heart and if he didn’t have the operation, he would slowly suffocate. The case had been tried in juvenile court because of the need for surgery. It made national headlines. A year and a half later the case shows up in my court, where surrogate parents were requesting guardianship of this young boy. There was a two-week trial. I found a way, in terms of creating some new law call the best interest of the child, and I found that these surrogate parents could be guardians of this child, and he survived the surgery. So in terms of the law, that was one of the high-point cases.

In terms of lifetime achievement, I really feel I had a big part in creating Sunnyvale, and making it the great city that it is today. It was a bond issue to build fire stations and parks and do underground for sewer and water, a number of civic projects. At the time in California, you had to have a two-thirds majority to pass such a huge bond issue as we did. I feel very happy I was able to get it done. It really made the city what it is today. That’s an achievement I’m very proud of.

I wanted to come back here and do something that would be a great help to our community, because I think Kaua‘i is a great place.

Was there a person who most influenced you?

I really have to start in high school. We’re talking about a little bit ago about what gets you inspired. I had this teacher, he opened my eyes to not only new ways of thinking, but also you can achieve. In my time, there was a feeling of real despair among Hawaiian boys, that they could not do any better than maybe working in a hotel or being a gas station operator or working for the telephone company, they couldn’t go any further than that. He really thought that I could do better than that. So it’s the mentoring. I’ve talked to many people who are successful, and you’ve always got to have a mentor, somewhere early on in your career, or when you’re growing up, to move you forward.

How about overcoming asthma in your childhood? What inspired you?

Glenn Cunningham. He was a runner in the ’30s who almost broke the four -minute mark of the mile. He was in a school fire, his brother was killed by the fire, his legs were badly burned and the doctors wanted to amputate. He refused. ‘You’re not taking my legs.’ That’s a story that always inspired me, how he was able to develop his legs back to health and to be able to be the runner that Roger Bannister eventually became. He was thought to be the first American that might break the four-minute mile. A great story, which inspired me because asthma just debilitated me. I was able to force myself, this ocean was my doctor, to overcome.

What would you say to people to encourage them to read your books?

I think the main part of the story, (“Kaua‘i Kids”) this was tells you the struggle of the poor Hawaiians to try and make it, and in this (“Rainbow over Kapa‘a”) he builds a dream, and goes after the dream. One tells the story of a kid that has no ambition, no knowledge of the world and finally tries to find a way to make a better life. Both are stories of struggles to try and be better, to succeed.

Somehow, I made it. But for the grace of God, I used to say that in court a lot. You see this guy that’s going to be sentenced to death or prison for 40 years or whatever, and I look at them, and I’d say, ‘But for the grace of God go I. I could have been that same kid.’