HONOLULU — With thousands displaced, at least 115 people dead and much of West Maui razed, the images of devastation and the anguish of survivors are not easy for anyone in Hawai‘i to process.

For children still developing social and emotional skills, managing those feelings can be even harder.

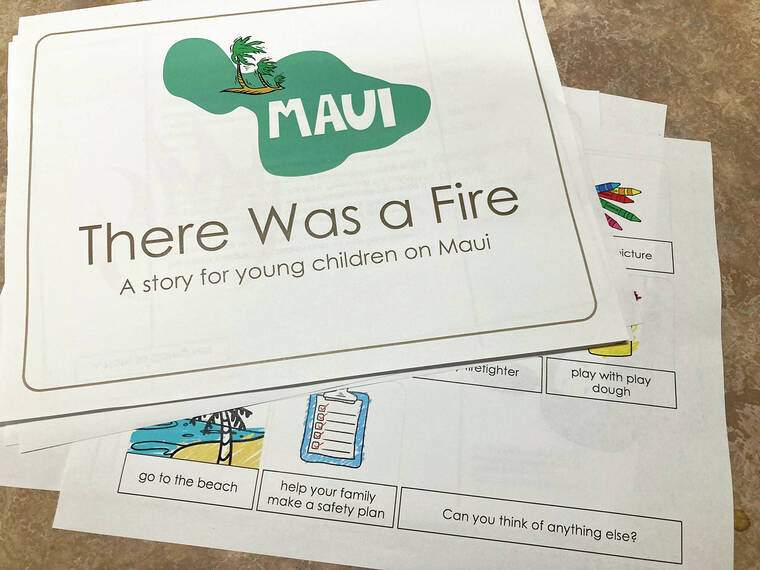

To help young children affected by the fires, Honolulu Community College early childhood assistant professor Elizabeth Hartline created “There was a fire A story for young children on Maui,” putting the story online for free and distributing it on-island through the University of Hawai‘i Maui College’s Early Childhood Education department.

“My hope is that this tool gives families a way to talk to their children about the fire,” Hartline said. “Everyone needs a story, and finding a story that describes your experience is a first step when we’ve gone through trauma to start healing.”

Hartline is no stranger to supporting children who have gone through harrowing events. As former education director and special needs coordinator at Bank Street Head Start in New York City, she oversaw childhood trauma responses following Hurricane Sandy, providing additional assistance to many other high-need families.

Immediately after she discovered that the fires had broken out on Maui, Hartline wanted to do whatever she could to help — and within a day of the fires, she had written, completed and released her story to the public.

“I don’t have much money. I can’t cook. I’m not there,” she said. “But I know how to support young children in traumatic times, so I want to be able to share that knowledge with families and caregivers on Maui.”

Written for keiki ages 3 through 8, the short story tells a simplified version of the fires, emphasizing that it’s normal and OK to feel strong emotions after such a traumatic event, and encouraging kids to talk openly with grown-ups about their feelings.

“Emotional intelligence is not something that we are born with,” Hartline said. “It’s something that needs to be cultivated and nurtured by caregivers. Even the process of identifying how you’re feeling is not something that comes innately.”

Hartline suggested playing pretend as much as possible after such an event, letting the child take the lead even if play takes a dark or disturbing tone, as doing so allows children to better process conflicting emotions.

“Play firefighter with them — let them explore what it would be like, because they then have the chance to rewrite the story for themselves in ways that feel better,” she said.

“When children play pretend, someone can die, and then they can wake up again. And then you can change the narrative — ‘Oh, the firefighters get there, and they save a cat.’ That is the primary way, in the early childhood classroom, that we support children dealing with trauma.”

Additionally, many children affected by the fires may feel a sense of helplessness. To combat this, Hartline recommended the importance of giving children a sense of control over their lives after such an alarming event.

“Empowerment for young children might look like getting to pick out what they wear, or getting to choose what they eat, or thinking about ways as a family that they can help other families,” she said.

“That might be going to volunteer, that might be writing their friends a letter, whatever it is, but thinking about what this trauma has taken away from their child and their family — not physically, but emotionally and cognitively — and thinking about ways that you can consciously and intentionally recreate these systems.”

Keiki aren’t the only ones dealing with strong emotions after trauma, though. Hartline stressed that caregivers should think about how to help their keiki process emotions without neglecting their own.

“We all know that this is going to be a long-term recovery, and you are going to be exhausted with your child sometimes,” she said. “And knowing ahead of time, like, ‘OK, what am I going to do if I’m too burned out to deal with them?’ is a great plan for your mental health, and your child’s mental health.”

Since its release, the story has also been distributed through Maui Head Start preschool sites and various relief organizations, and there have been discussions about publishing the story and distributing it more widely, Hartline said.

“Liz’s book is such a treasure. It helps children process the trauma of the devastating fires in our Lahaina and Kula communities,” said Dr. Felicitas B. Livaudais, a Maui-based Kaiser Permanente pediatrician.

“It normalized big feelings and grief,” said Livaudais. “It gives them tools on how to deal with their emotions. It reassures them that there are adults who are helping and working hard every day so they can be safe. It gives parents a guide on how to communicate with their children during this very difficult time. I am giving it to all of my patients.”

Copies of “There was a fire” can be found online at https://hawaiiactionstrategy.org/maui-wildfire-resources, as well as on Hartline’s Instagram page, @ece_liz13.

“I’m just very grateful that this is getting to a lot of children, and makes me feel like I can do a little bit to support them,” she said.

•••

Jackson Healy, reporter, can be reached at 808-647-4966 or jhealy@thegardenisland.com.