LIHU‘E — A newly published report detected sucralose — an artificial sweetener commonly found in manufactured foods — throughout Kaua‘i’s streams and rivers, indicating nearly islandwide water contamination by human sewage.

“There’s no doubt in the science community that sucralose is an excellent indicator of the presence of human wastewater in the sample,” said Carl Berg, lead researcher and Surfrider Kaua‘i senior scientist.

“There’s no doubt. Sucralose doesn’t degrade, it doesn’t break up, it doesn’t adhere, it’s ubiquitous — it’s found all over the place. It is a scientifically demonstrated indicator of human wastewater in your sample, wherever your sample’s from.”

Both Surfrider and the state Department of Health regularly test Kaua‘i’s waters for the enterococcus bacterium, a federally recognized indicator of fecal presence in water. However, the department has on multiple occasions declined to attribute enterococcus presence to human waste, arguing the bacterium could have came from animal feces or naturally occurring bacterial colonies.

To counter this, the

Surfrider researchers chose to test for both enterococci and sucralose in their study. Because

sucralose does not occur naturally, and because it’s largely left intact as it exits the human body, the researchers say its presence across Kaua‘i’s waters leaves little doubt as to what’s polluting the island’s streams, rivers and beaches.

“If it goes right through your body and it’s only man-made, then if you find it in the environment, you know it came from a human … Nobody’s going out there and dumping sucralose — it’s coming from human consumption. Birds don’t eat it. Dogs don’t eat it. It’s coming from humans,” Berg said.

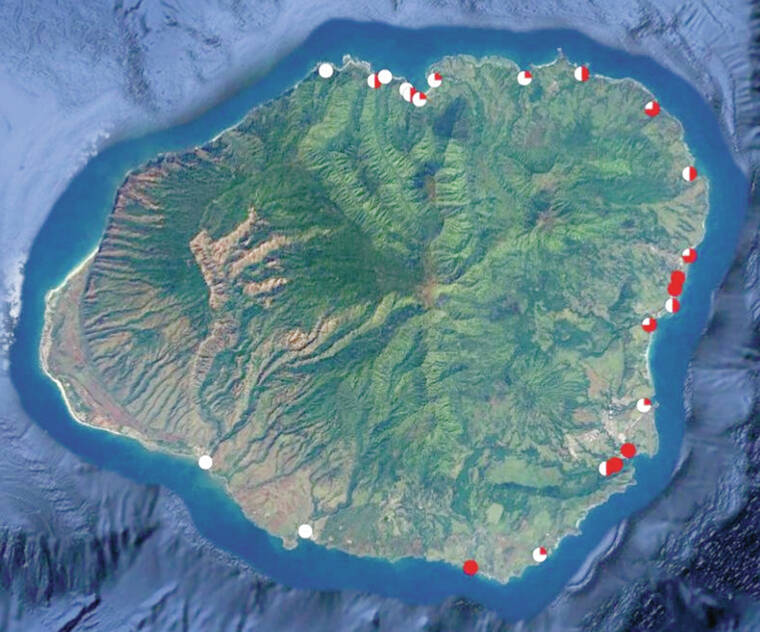

Of the 24 sites tested, only five waters (Lumahai, Limahuli and Waikoko streams and Hanapepe and Waimea rivers) tested negative for sucralose over four sets of sampling.

All 19 other sites tested positive for sucralose at least once, with all 24 sites testing positive for enterococcus.

As for where he believes the pollution is coming from, Berg did not mince his words.

“It’s coming from cesspools,” he said. “We’ve been saying this all along.”

Kaua‘i’s approximately 14,000 cesspools release untreated wastewater into the ground, contaminating the island’s groundwater.

Over time, the contaminated groundwater seeps into streams and rivers before being dumped into nearshore waters, contaminating each body of water it passes through.

In an attempt to limit this pollution, the state Legislature passed in 2017 Act 125, requiring all 88,000 of the state’s cesspools to be replaced by 2050, although the high costs of septic tank conversions has slowed these efforts.

However, Berg suggested the state Department of Health may now additionally be required by law to bolster public health precautions.

Under Hawai‘i Administrative Rule 11-54-8, warning signs must be posted “at locations where human sewage has been identified as temporarily contributing to the enterococci count.”

“In the past, (the Department of Health has) only put that warning sign up if they saw a pipe leaking or a cesspool leaking — if they actually saw the sewage,” Berg said. “They otherwise did not put up the sign. Now, we’re saying, ‘You don’t need to see it, because this chemical is showing you that human wastewater is there.’”

“I’m hoping the result of this highly accredited scientific study will lead the Department of Health to putting up warning signs in the other areas where there is high public risk,” he continued.

“We need to get a sign up on the Nawiliwili Stream. We need to get a sign up at Waipa Stream. We have a sign in Hanalei and we have a sign in Puali — what about the other streams?”

The report can be read in full at link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s10661-023-11545-7.pdf?pdf=button.

Health department responds

In response to the study, the Department of Health’s Clean Water Branch (CWB) did not refute the researchers’ findings.

Still, the branch’s Engineering Supervisor Darryl Lum noted that under federal rules, the branch itself cannot currently make use of the researchers’ approach.

“The method used by the authors seems compelling for routine monitoring for the detection of cesspool contaminated waters; however, CWB can only use methods approved by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency,” Lum said. “The CWB encourages the authors to submit the study for approval through EPA’s Alternative Test Procedures program under 40 CRF 136.4.”

Lum continued, noting that several independent studies have concluded enterococci can grow and multiply without a human source.

Because the Clean Water Branch’s current testing methods cannot differentiate between naturally occurring enterococci and enterococci from feces, the branch continues to notify the public whenever bacteria levels at coastal beaches exceed state thresholds.

“The CWB agrees that cesspools pose a problem in that they can potentially impact human health, as well as the aquatic life in Hawai‘i’s waters, and should be converted as soon as possible,” Lum added.

•••

Jackson Healy, reporter, can be reached at 808-647-4966 or jhealy@thegardenisland.com.

Some of the assertions here are misleading. The difference between a cesspool and a septic tank is that a cesspool is just a container for sewage that lets it slowly percolate into the soil. A septic tank has two containers. The initial one holds the sewage where it presumably is acted upon by bacteria (which can also exist in a cesspool), and then liquid passes into a second tank, and then out a pipe into a “leach field”, where it percolates into the soil.

Thus, since sucralose does not break down, a septic tank will put just as much sucralose into the ground water as a cesspool. Note also that sucralose can pass from the body in the urine. Thus, anywhere there are swimmers or surfers there will be sucralose in the water.

The real test, therefore, for sewage contamination remains the presence of E-coli in the water.

Surfrider’s water tests have been purposefully misleading for years.

All Kauai needs sewer systems!!! Nice that Hanapepe and Waimea had low sucrose levels- they both have sewer systems for the towns and surrounding area for over the past 20 years!!! Our state and county need to stop spending money on non- essential things and focus on expanding Kauai’s sewer systems…

This is what part of the capital improvement budget should have been allocated to. It seems like the water company has swept this under the rug for years and our political leaders have accepted that as a viable solution. Let’s clean up our island! We won’t need a bigger airport if nobody wants to come here due to human feces in the water.

We all understand this issue is the biggest barrier to affordable housing- but why our politicians and county officials don’t fight for sewer systems on Kaua’i- I wonder if there is a conflict related to our many private sewer systems- makes you wonder if politicians are getting financial support from private sewer companies to limit county managed sewer systems

I live on a sewer system. Maybe it’s time to see how well the systems on Kauai are treating the sewer before being released into the ocean.

Sucralose is non-human food and is a burden on human health. Yet it appears readily in human excretion. In the long run Sucralose may be more detrimental to human health than E. Coli, a Bacteria in human feces that cannot survive in Nature’s Ocean Salt Water, thank goodness.

Get Sucralose sugar out of the human diet along with other unnatural sweeteners and non-food chemicals in our Supermarket groceries…much of which are merely low to non-nutritious snack food.