Hole hole bushi are songs that Issei (first generation) immigrant Japanese women sang during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, while tediously stripping dry sugarcane leaves off cane stalks with machetes in Hawai‘i’s cane fields.

Hole hole means sugarcane leaves in the Hawaiian language, while bushi is a Japanese word for song.

Their songs expressed their joys and sorrows, the hard work they endured, the rigors of early plantation life, relationships between men and women, and reminiscences of their hometowns in Japan, and so forth.

Although their melodies were based on folksongs from their prefectures in Japan, the verses were of their own creation such as:

Ni-hon de-ru tok-ya yo — When I left Japan

Hi-to-ri de de-ta ga — I was all alone

I-ma ja ko-mo a-ru — But now I have children

Ma-go mo a-ru — And grandchildren, too

One Issei woman once described hole hole bushi as “painful songs.”

Likewise, they are aptly referred to as Hawaii’s version of the blues, which originated in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s.

Gerald Hirata, the president of the Kaua‘i Soto Zen Temple in Hanapepe has said, “Almost all of these women are gone, but not forgotten.”

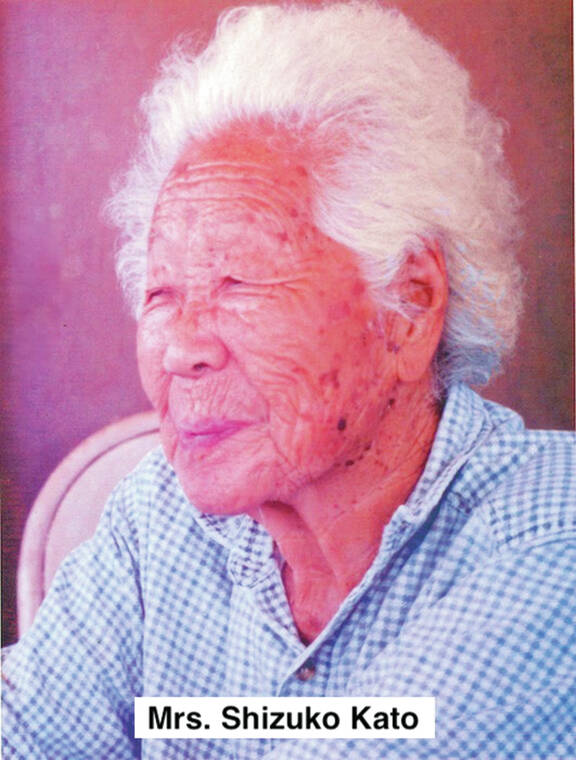

Among the not forgotten is Mrs. Shizuko Kato (1905-2004), a former temple member.

A recording of her singing hole hole bushi has been preserved by Hirata.

Mrs. Kato was born in Hiroshima, Japan in 1905, came to Kaua‘i as a picture bride in 1921, and sang these songs while working in the cane fields of McBryde Sugar Plantation.

Some years ago, the Hanapepe Soto Zen Temple also hosted a performance of hole hole bushi singers Cara and Lacy Tsutsuse of Honolulu.

They were the students of Honolulu music teacher Harry M. Urata (1918-2009), who’d single-handedly located the Issei women who first sang hole hole bushi and recorded their songs before they would have faded into oblivion, and then taught them to his students.

“Harry Urata is the person credited with saving these songs from extinction,” Hirata said.