Anthropologist Kenneth Emory (1897-1992) was born in Massachusetts. In 1900, he moved with his parents to Honolulu, where he attended Punahou and became fluent in the Hawaiian language.

Following his graduation from Dartmouth in 1920, he returned to Hawai‘i to take a position as an ethnologist at Bishop Museum. And in 1921, he made the first archaeological survey of Lana‘i.

In 1922, he studied anthropology at UC Berkeley and received his master’s degree at Harvard. A doctorate from Yale followed in 1946.

During the intervening years, Emory participated in the Kaimiloa Expedition of 1924 to study the archaeology of the Fanning, Christmas, and Malden atolls of Kiribati, and Tongareva Atoll in the Cook Islands.

He also investigated the archaeology of the Society Islands and several Tuamotu atolls in 1925, which he augmented with a thorough archaeological survey of the Tuamotu Archipelago during 1929 through 1931.

On Kaua‘i, at the Wailua birthstones in 1933, Emory uncovered a stone artifact that was typically Tahitian — a discovery that substantiated Hawaiian tradition indicating that Tahitians had settled in Hawai‘i in the 1200s.

The year 1934 found Emory with the Mangarevan Expedition surveying the natural history of the Mangarevan and Tuamotus islands.

And, in 1947 and 1950, he participated in expeditions to Kapingamarangi in Micronesia.

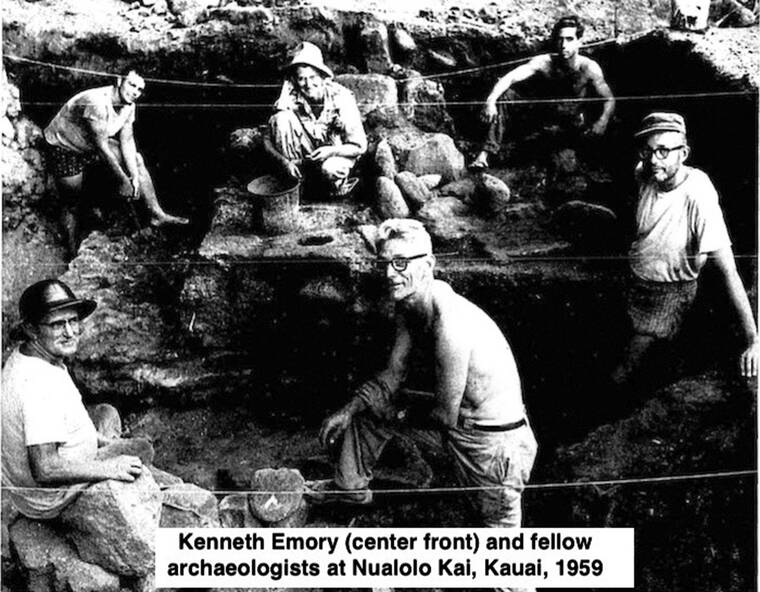

Emory’s work in Hawai‘i proceeded in earnest during the 1950s by his leading archaeological digs at Nualolo Kai on Kaua‘i’s Napali Coast, South Point on Hawai‘i and on Moloka‘i and O‘ahu, where he established settlement dates for early Hawaiians through carbon dating.

In particular, Emory found ancient artifacts in a cave in Kuliouou Valley, O‘ahu, which by carbon dating determined humans had used the cave as early as 1004 A.D., while his digs at South Point established links between Hawai‘i and the South Pacific.

Likewise, during 1958 and 1959, his excavations at Nualolo Kai showed that Hawaiians had inhabited the area since at least 1389 A.D., plus or minus 150 years, and that a turtle shell tattooing instrument found there was a Marquesan type.

Other discoveries further indicated that the Marquesas were the starting place for the first Polynesian migration to Hawai‘i.