KALAHEO — Nearly a decade ago, federal Public Defender Alexander Silvert was assigned to represent a man accused of stealing a mailbox, setting into motion an investigation that blew the lid off what would become known as “the greatest corruption case in Hawai‘i history.”

The defendant, Gerard Puana, was charged with a felony offense for the theft of a mailbox owned by his niece Katherine Kealoha, the third-ranked Honolulu prosecutor, and her husband, Honolulu Chief of Police Louis Kealoha.

Over the course of a bizarre and revelatory case, Silvert was able to prove that Puana was actually being framed in a sprawling conspiracy to cover up Katherine Kealoha’s financial crimes.

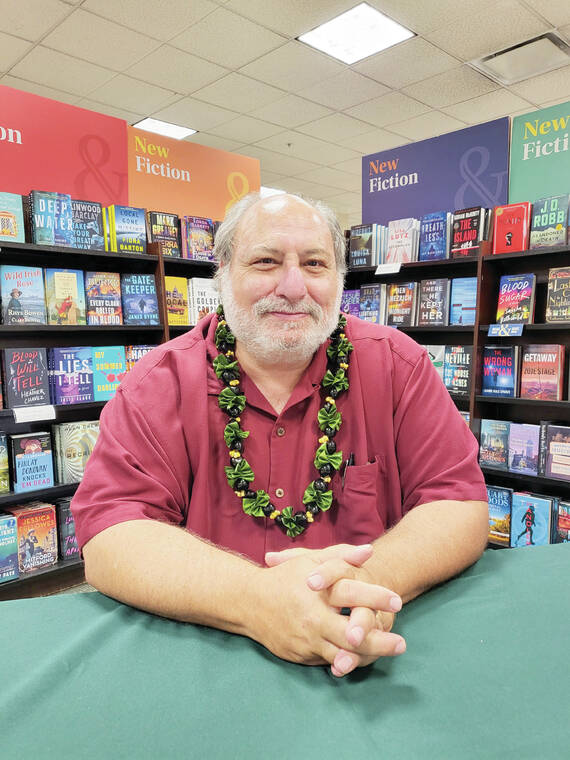

Silvert then helped instigate the prosecution of the Kealohas, who are now serving time in federal prison along with others affiliated with the scandal. Now retired from the courtroom, he recently published a book about the case, “The Mailbox Conspiracy.”

On his visit to Kaua‘i for a book signing at Talk Story Bookstore in Hanapepe, Alexander Silvert sat down with The Garden Island to talk corruption, reform and the writing process.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

TGI: “The Mailbox Conspiracy” reads more like a true crime novel than the sort of legal documents an attorney would write for the courtroom. What was the process of learning to write in this style like for you?

AS: I never wanted to be a lawyer. I actually didn’t go to law school to be a lawyer, I just happened to fall in love with doing trial work. So I’m not writing like a lawyer, because that’s just not my style. I wrote it as a whodunit.

We wanted to make sure that the law in there is easy to understand, and we wanted to write it as if you’re going along with me as I uncover the evidence that reveals the frame-up.

The fun part for me was coming up with titles and figuring out how to end a chapter, to lead readers to want to read the next one.

TGI: One thing that stands out to me about the case is that the mailbox frame-up job seems incredibly sloppy. Do you think that that was more of a function of the Kealohas being inept or arrogant?

AS: I’m convinced it was arrogance. But it was arrogance in that, when they understand how the system works, they were banking on it working for them. Katherine knew that the prosecutor’s office would prosecute the case. The Honolulu Police Department was investigating the case. So they could control all aspects. They didn’t think anybody would really investigate it, and they would use the system and the way it works to their benefit.

TGI: After the Kealoha case and the recent bribery scandals at the state Legislature last year, there has been a huge focus on corruption, with the Foley Commission proposing a series of new reforms, some of which are now making their way through the statehouse. What are your thoughts on those proposals?

AS: I think the Foley Commission was a great first step, but it can’t be the end. There are moments in history where change can happen, but they don’t last long. The status quo doesn’t want it and it’s going to fight back.

My book talks a little about how they refused to make real change after the (Kealoha) indictment. That was a moment in time when change could happen. There was some movement, but not enough. And here we have another moment in time, and we have to hold people accountable.

TGI: Are there particular proposals that you latched on to?

AS: (The Foley Commission) recommended new criminal statutes dealing with fraud and corruption, and I think that’s critically important because the state has a gap.

All these corruption cases we see now are being prosecuted by the feds. There are a lot of institutional reasons why this is happening, and one of the reasons is that there really aren’t equivalent criminal statutes on the state books that allow these kinds of prosecutions.

Then there are the open government measures, which you can already see, they’re fighting tooth and nail against.

TGI: After seeing it firsthand, do you feel like the culture of corruption is worse in Hawai‘i than it is elsewhere?

I’m from Boston, New York and Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, if someone in the sanitation department got arrested for taking a bribe it wasn’t just one person — it was the entire department. So, I don’t think we are worse than any other state.

The unique problem that Hawai‘i has is with whistleblowers. If you’re in Philadelphia and you’re a whistleblower, you can move your family to Pittsburgh or Harrisburg. You’re still in the state you were born and raised in, you still have your friends, and you can go get another job.

In Hawai‘i, if you’re a whistleblower, you need to leave the state. That means leaving your family, your ‘ohana, everything. It’s very difficult for whistleblowers to come forward and say anything because of our unique situation.

TGI: Kaua‘i recently had its own public corruption case with former County Council Member Arthur Brun convicted of leading a drug smuggling operation. Do you think the problem of corruption on neighbor islands can be worse because there isn’t as much scrutiny here?

AS: Is corruption worse on the neighbor islands? I think it can be more egregious because it’s local, smaller and less controlled. But is it more prevalent? No, because all the power and money are in O‘ahu.

TGI: About a week ago, there was a settlement where Gerard Puana was granted $2.85 million by the city of Honolulu. Do you feel with that settlement and the Kealoha sentences, that justice has been done in this case?

AS: I’m very happy about that settlement, but it’s too little. There are two aspects to every settlement. One is making the victims whole. The other aspect is to punish the wrongdoers so they don’t do it again. If one of the goals was to punish the city and county to make them see the light and make sure this kind of thing doesn’t happen again, this won’t do it.

What they’re saying is that it’s just a few bad apples, we’ve cut them out, and that’s what they always say. That’s why I wrote the book, not just to tell about what happened, but because it’s a textbook example of systemic corruption. There were lots of people and institutions that knew what was happening and didn’t come forward, and that’s systemic corruption.