LIHU‘E — New legislation, building projects and fallout from COVID-19 shook up the Kaua‘i housing crisis in 2021, although it’s too early to fully understand the past year’s ramifications.

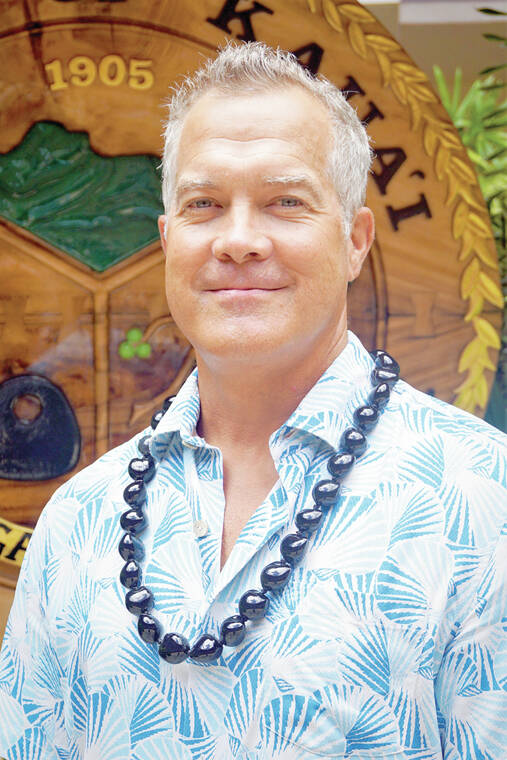

County Housing Agency Director Adam Roversi said the coronavirus pandemic drove out-of-state homebuyers and renters to Kaua‘i in 2021.

“Anecdotally, (they) appear to have significantly driven up home prices and rents, exacerbating an already-critical housing shortage,” Roversi said.

The median sale price of a Kaua‘i home in November was $1,213,000, up 57% from 2020, according to Hawai‘i independent real-estate firm Locations.

Kaua‘i County Councilmember Luke Evslin agreed the influx of wealthy individuals looking to work from new homes stands out as a key development in the housing crisis.

“If you’re working for Google, then you can afford to outbid anybody working on Kaua‘i, for the most part,” Evslin said.

The true scope of wealthy remote workers’ impact on the housing crisis is unknown. But Evslin believes it might have been mitigated by newcomers’ apparent focus on high-end, ocean-front properties, rather than working-class neighborhoods.

“It’s taken away inventory, but in a lot of ways that’s inventory that probably wouldn’t have necessarily gone to locals anyway,” he explained.

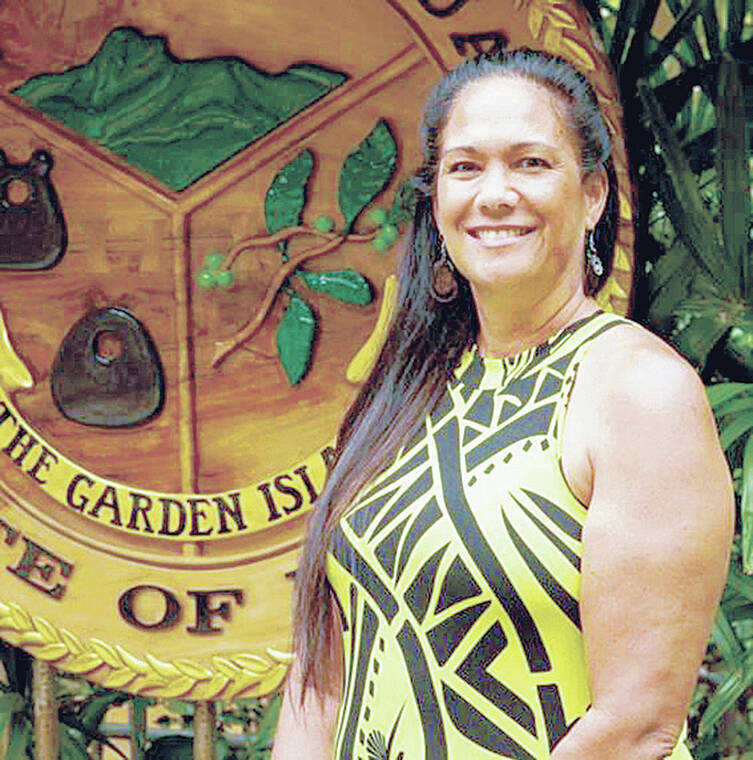

Properties’ high price tags and increased rent rates also exacerbated the Kaua‘i labor shortage in 2021, according to county Office of Economic Development Director Nalani Brun.

Brun described the island’s dominant hospitality industry as historically populated by transient workers from off-island, including many recent high-school or college graduates seeking sun, sand or adventure.

“This workforce took many of the jobs, often part-time and at a lower pay scale, so they could follow their dreams,” she explained.

Many also lived under one roof, pooling their resources to make rent payments each month. But very few of these homes are now available, and those that remain have become unaffordable to low-income workers.

“(This makes) a part-time job a choice that can’t pay the bills and still give a transient worker the freedom they are looking for,” Brun said. “Thus, we are not getting that support worker that we have typically had to support us.”

The OED director was careful to note that the lack of affordable housing is not the only issue exacerbating the island’s labor shortage: residents have given up second jobs to care for children and elders, and have found other ways to make money, including the car-rental platform Turo, or moved off-island for other opportunities.

Others have simply reevaluated their priorities.

“Many are just looking at their lives and what they want out of it,” Brun said. “Working two or three jobs does not seem to meet the ideal.”

Eviction tsunami avoided

The end of state and federal eviction moratoriums last summer appeared set to unleash a wave of evictions on Kaua‘i.

State Reps. Nadine Nakamura of north and east Kaua‘i and Troy Hashimoto, who represents areas of Maui including Wailuku, created a bill that became Act 57, which overhauled the state landlord-tenant code, to forestall what Nakamura called a potential “tsunami of evictions” in the wake of COVID-19.

But the storm never came.

Both Roversi and Kaua‘i Economic Opportunity, the island’s designated landlord-tenant-mediation center, report preliminary findings that show no significant uptick in evictions as compared with pre-pandemic numbers.

Charlene Johnston, KEO’s interim mediation director, is surprised by the relatively low demand for the nonprofit’s mediation service, which seeks alternatives to eviction when landlord-tenant disputes arise.

Johnston credits the Kaua‘i Federal Credit Union, the organization operating the island’s federally funded Coronavirus Rental and Utility Assistance (CRUA) Program, with an outreach campaign that educated landlords and property managers. She believes KFCU’s efforts may have prevented evictions that might have otherwise occurred.

“A number of (property managers) are really well-trained in the process now,” Johnston said. “They know how to get their tenants connected with KFCU and go through the (CRUA) process.”

KEO serviced 115 unique inquiries through its Eviction Diversion Mediation Program at time of publication.

Most of these cases circumvented mediation by resolving payment disputes through financial assistance under CRUA. But some cases did enter mediation, for which KEO has a 100% success rate, meaning all participating landlords and tenants resolve their disputes without resorting to court or eviction.

CRUA has received 2,176 applications for assistance to date, according to Roversi, for requested totals of $13.85 million in rent and $567,000 in utilities. The program has distributed $12,557,756 in rental assistance and $417,721 in utility assistance, with another $548,727 in rent and $42,240 in utilities approved and pending issuance to applicants.

Legislator’s projections

Evslin sees the October 2020 passage of County Bill No. 2774, which changed zoning requirements in a bid to generate housing growth, and the council’s recent passage of a cesspool-conversion program, as two important steps on the long road toward readily-available, affordable housing.

The cesspool-to-septic program, Evslin explained, is intended to mitigate a chronic lack of infrastructure that prevents many Kaua‘i households from building additional affordable rental units on their property.

“Allowing ARUs almost islandwide essentially doubled everybody’s allotment of density for residential property everywhere outside of Hanalei and Ha‘ena,” Evslin said. “But you can’t take advantage of any of this if you’re not on sewer, for the most part — and you certainly can’t do anything if you’ve got a cesspool.”

Almost half of the island’s 40,000 homes have cesspools, according to Evslin.

The program, to be implemented by the CHA, will utilize $1.2 million in forgivable loans sourced from monies disbursed by the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

Evslin, along with Councilmember Bernard Carvahlo, has also introduced a bill that would curb future developers from creating covenants, conditions or restrictions that prevent homeowners from renting out privately owned space.

“The model for development on Kaua‘i is to make these higher-end developments, which are in some sense exclusionary by nature,” Evslin said. “They’re made to cater towards upper-income, and they make it so that you can’t even get a rental unit or accommodate for your kids.”

Evslin has set his sights on vacant homeownership and transient vacation rentals as well, claiming wealthy from outside Kaua‘i have “parked” their money in local houses to take advantage of low property taxes.

The councilmember estimates one in eight Kaua‘i homes are currently vacant, having been purchased as investments or second homes.

“We need to discourage that through property taxes,” he said. “If you’re going to keep a house empty, then you should be paying a whole lot more for that, to ensure that we can build a house for somebody else.”

Current projects

Roversi reported the CHA has issued requests for proposals for 85 affordable rental units at its Lima Ola development in ‘Ele‘ele.

The agency will issue additional requests for proposals for 38 single-family homes and a 24-unit supportive-housing project for homeless families in Lihu‘e this month.

Its 53-unit affordable rental project on Pua Loke Street in Lihu‘e, developed by the Ahe Group, completed construction of its third and final building earlier this month.

Other ongoing initiatives include an increasing number of federal Section 8 rental-assistance vouchers; continued pursuit of affordable housing in Kilauea; and the acquisition of three single-family homes to be rehabilitated and sold to qualifying local residents.

An annual point-in-time count of the Kaua‘i homeless population, and community planning for affordable housing on a portion of the county’s Waimea 400 property, are also slated for early 2022.

Meanwhile, Kaua‘i Habitat for Humanity is wrapping up Phase Two of its ‘Ele‘ele Iluna development on the island’s Westside, which will total 125 affordable homes when completed.

“Among the seven Habitat affiliates in Hawai‘i, Kaua‘i Habitat is the only one actively pursuing subdivision development to address the housing crisis,” Executive Director Milani Pimental said.

Kaua‘i Habitat, which has built 200 homes and rehabilitated another 36 since its establishment in 1992, is also working on a development in Waimea.

”We’re just getting ready, waiting on final approvals, so that we can begin building our 32 single-family homes on the property,” Pimental said.

The Waimea site already features 35 multi-family rental units built by the Ahe Group.

This article was updated at 7:35 a.m. on Monday, Jan. 3, 2022, to correct a statement attributed to County Councilmember Luke Evslin. One in eight homes are estimated to be vacant, not 180.

This was updated at 11:17 on Monday, Jan. 17, 2022, to note Kauai Economic Opportunity had serviced 115 unique inquiries through its Eviction Diversion Mediation Program at time of publication. A previous version of this article cited an inaccurate number and terminology in reference to the above KEO activity.

•••

Scott Yunker, reporter, can be reached at 245-0437 or syunker@thegardenisland.com.

Sounds like they want to encourage substatial growth. What about the traffic problem that is already out of control? We should encourage people to have a secound home or empty home. A person who is here 4 weeks a year has much less inpact on the island.

Traffic is created by mostly tourists who don’t live here, and for that person who stays here 4 months a year that’s why we have no affordable housing..we should tax the shit out of them guys.

Every newly elected council member should be required to take an Economics 101 class before they are sworn into office. Demand for housing on Kauai far exceeds the supply but the people in charge are not addressing how to fundamentally change that equation legally. The Department of Hawaiian Homelands holds about 1200 acres of vacant land suitable for residential homes with eligible Hawaiians on their waitlist. That’s 1200 acres, 2400 homes, 4800 residents who could live there. That would significantly reduce the demand for Kauai housing. But there is little to no development of these vacant lots. Why ?

people with high dollar homes….could care less about their property tax bills…haha…..meanwhile, if your looking for revenue… is Zuckerberg filing state income tax returns…??

“If you’re going to keep a house empty, then you should be paying a whole lot more for that, to ensure that we can build a house for somebody else.”

If you’re going to keep a house empty, then you should be paying a whole lot less for that, as you are requiring fewer services from the county/state.

Ok. I don’t get it? The Government is going to tell a homeowner, who worked hard and took investment risks to have a rental home in order to make money to feed his family, must now support and provide the renter, who can’t afford to pay as agreed, with a free place to live at the homeowner’s expense? Why? Because the Government says so? Nah. That’s what the Communist China, Russia, and North Korea bullies would do! Not the United States of America! When are the rather dull, never made it in real life, Politicians going to figure out that the Constitution of the United States was written to curtail the Government and prevent it from being the bully in town!

The more you build the more traffic, congestion, overcrowding and destruction of the island you create. Their should be a moratorium on all new construction EXCEPT for affordable housing for existing residents of the island who have been here ,say 5 years or more, That way housing is built for those who need it and not rich outsiders. Of course that will NEVER happen because the island is so corrupt

Great! Let’s keep selling off the island to ZUCKERBERG and billionaires. 20K a night stay a 1 Halanlei resort but nobody can glamp. Billionaires island here we come. Good luck with that community of complainers.

I think if contractors want to build 20 high end homes, make them build 40 truly affordable homes first or “no permit”

Time to start playing hard ball with these greedy money hungery developers

Thank you Kauai County Council for expanding ADU/ARU options… but also need to allow ADU and ARU on Some AG zoned lands that have adequate septic and infrastructure in place.

Also agree with statement about DHHL needs to get moving and build for those Hawaiians on their long waiting list….