Topping the list of the most-geographically isolated populations in the world, Kaua‘i is over 2,000 miles away from California, the state supplying the Garden Island with the majority of its food.

In 2012, House Bill 2703 was passed by the state House of Representatives, painted the dire state of Hawai‘i’s food security and brought it to the nation’s attention.

Within the seven-page document, it was stated that “Hawai‘i’s reliance on out-of-state sources of food places residents directly at risk of food shortages in the event of natural disasters, economic disruption and other external factors beyond the state’s control.”

Though this conversation entered the public sphere nine years ago with the passing of this bill, it ended shortly thereafter.

In the decade that has followed, many of the sustainability and food-security goals that were set were abandoned, and a disproportionate amount of economic and political focus was sequestered toward tourism instead of food sovereignty. This has left the state with an overdependence on imported food.

It is so crippling, in fact, that over 90% of the food ending up on the state’s plates each day and over 70% of the energy powering Hawai‘i’s cars and homes is coming from the continental United States, statistics that would leave just seven to 11 days’ suppy in the face of a natural disaster or transs-Pacific transportation shutdown before residents would begin finding the gas stations running empty and grocery stores out of stock.

As threatening as the situation may sound, there is no need to hit the panic button just yet. Looking into traditional Hawaiian farming practices can offer all of the solutions the islands are now seeking when it comes to increasing local (and organic) food production, some say.

Prior to Captain Cook’s arrival, the Hawaiian Islands were completely sustainable and food secure. It was only with the introduction of Western land-use practices, including large-scale monoculture, and the idea of private property, that the islands began to outsource their energy and food needs. If Kaua‘i can commit to

understanding how the indigenous Hawaiians were farming the land and feeding themselves, modern-day residents can too find harmony with the island and stability for future needs, experts say.

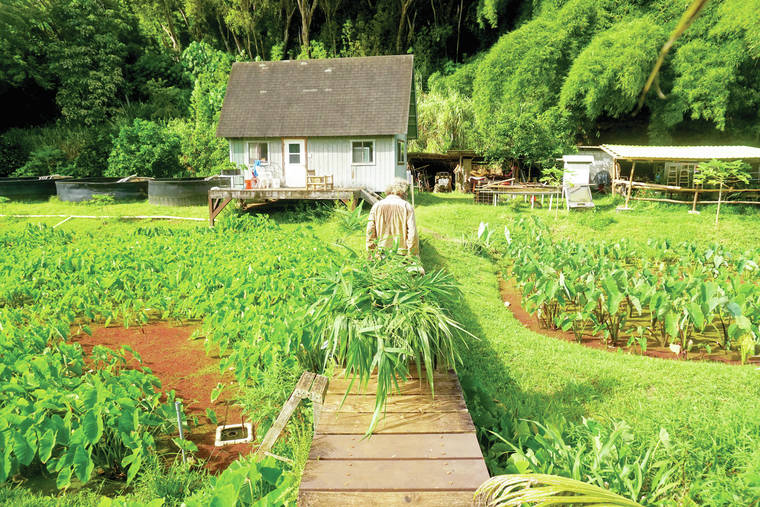

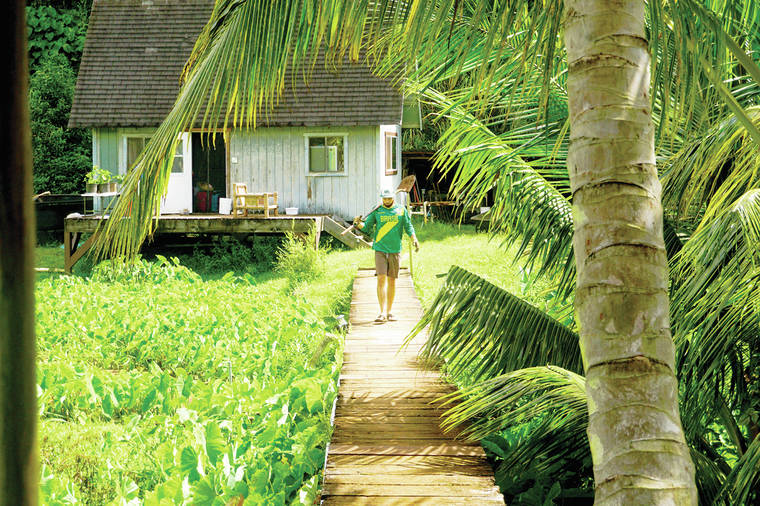

If there’s anyone who understands the importance of food security, perhaps it’s Don Heacock, owner of Kaua‘i Organic AgroecoSystems Farms in Niumalu.

“We’re going back to the future now,” Heacock says of his sustainable, ecological and organically integrated-aquaculture (tilapia), agriculture-agroforestry (kalo) farming system. “A lot of people are becoming aware that modernization and current development on Kaua‘i is not sustainable and is causing ecological damage. At KOA, all I’m doing is trying to restore what Hawaiians invented over 550 years ago: an integrated fish-taro production system like the loko ia kalo (fish yard with taro), but also include fruit- and nut-tree orchards, avocados, ulu and dairy water buffalo.”

As simple as that may sound, it has been anything but.

When Heacock received the land in 1987, it was completely overgrown with impenetrable amounts of hau bush. He laughed as he recalled the year he spent clearing out just the first acre in order to restore the taro fields and begin growing food.

“The ahupua‘a system is a holistic, community-based, comprehensive watershed-resource management system that included the adjacent coral reefs. It is an incredible concept. It was far beyond anything Europeans or anybody else has come up with. In this case, necessity was the mother of invention, because the Hawaiians had nowhere else to go for food besides the Hawaiian Islands. They had to figure out how to produce more food for more people as easily and efficiently as possible and, on Kaua‘i, feed approximately 100,000 people.”

In modern-day Kaua‘i, the need to be food-secure is again being felt.

“We now have an urgency to produce food. We are facing the largest global food shortage that the earth’s ever seen,” Heacock warns. He goes on to explain how in contrast to modern-day industrial agriculture, the ahupua‘a system “was unique, it was holistic, it was highly integrative and run by the community.”

Buying locally grown, organic food products is one way to contribute to an increase of food security on the island.

By sourcing food locally, residents can begin to make massive steps forward towards food security for the state.

According to the Increased Food Security and Food Self-Sufficiency Strategy released by the state Office of Planning in the Department of Business Economic Development &Tourism in cooperation with the state Department of Agriculture, “replacing just 10% of the food Hawai‘i currently imports would amount to approximately $313 million which would remain in the state.”

However, the benefits extend far beyond increased local cash flow and job production.

“It’s important that in addition to economic profits, we’re also making environmental profits,” Heacock explains.

Through his work at KOA, he’s seen the return of endangered waterbird species, like the Koloa duck, alae ula and Hawaiian stilt, to his property. The soils, too, have become richer, and his food forest has flourished with a huge variety of fruits, vegetables and herbs.

“We also make cultural and social profits,” he adds. “That’s what we’re making right now in education — we have to teach the next generation how to farm.”

All in all, the solution to the rising threat of food-insecurity lays in the hands of local farmers in the islands.

Supporting integrative, holistic and organic operations will lead to economic growth, environmental stability, cultural preservation and, perhaps most dire, security in case of emergency, he said.

“O‘ahu will never be able to feed itself. There’s almost a million people living there, and that’s going to be dependent on Kaua‘i, Moloka‘i and the island of Hawai‘i to feed O‘ahu. But first we’ve got to feed ourselves,” Heacock said.

Thanks for this article. It needs to be in the headlines of the Garden Isle newspaper!

The ahupua’a system of land management requires dictatorial control of all the lands and waters throughout an entire ahupua’a, including control over the lives of the people living there. That’s the only way to make sure that streams do not get polluted; ditches get dug and are kept free-flowing to ensure crops have a good water supply; fishpond walls are well-maintained while fishing in streams and ocean is strongly regulated according to spawning seasons; industrial waste and human sewage are carefully controlled; etc. Such rigorously managed coordination requires a konohiki — a land-management dictator — who will not tolerate violations of his regulations by private landowners or freedom-seeking libertarians. And who will hold all that power? Well, of course it will be the the “indigenous people” who regard themselves as children of the gods and siblings of the ‘aina from hundreds of generations back. The ahupua’a system is a sweet dream of a Hawaiian sovereignty utopia founded on no private ownership, no individual rights, no democratic decision-making, no respect for racial or cultural differences. Just say no.

It’s too bad that Kauai grown produce is not featured in our grocery stores and Costco and every restaurant menu on this island

Where can I sign up, I have land, no machines and no help jus me and families to feed let’s go.

Conditions?

where on island are you?

In response to this excellent article, I entered Hilo Agriculture university in 1980, wanting to gather more knowledge about being able to grow enough food to feed the districts of Hilo, Hamakua, and Puna. Over the years, I realized the state government was only giving lip service to the large number of young people interested in sustainable farming

A Native Hawaiian concept, no Native Hawaiians interviewed.

Article shows the problem of land and power in Hawai’i without directly writing about it.

It’s always shocking to me when a reporter writes a lengthy article and completely ignores addressing the simple rules of economics. How much does it cost to produce food on Kauai compared to producing the same food in California or Mexico and shipping it to Kauai ? There’s a reason why large scale food production went out of business on the island years ago. It’s too expensive to produce here.

You comment mentioned ‘there’s a reason why large scale agriculture left the island’

Stop right there. That is where we go wrong. You can’t grow quality on a large scale, monoculture requires too much intervention with toxic chemicals to be good food. When you buy from a local farmer, he often lives on the land, and generally doesn’t care to douse it with chemicals, which are expensive to purchase and apply. Please consider buying local first- if we don’t support these hard working families they just might have to quit producing fresh food, and get a ‘real’ job.

In my opinion, there is no finer calling than

growing sustenance for your island O’Hara.

And don’t even get me started on the inhibitory tax structure on ag production…

Compared to Ancient Ways of Hawaiian Sustainable Agriculture, what are our chances for survival being we are dependent on all the poisinous chemical sprays, including on the food, and under your arms.

The store shelves and gas stations of just Iniki were empty before the storm even it…we are crossing the abyss on a stretched out spider web’s thread…!

Can we survuve eating RoundUp Ready poison saturated corn seeds…

We don’t need Vaccines to survive, we need natural food…!

We have prisoners and peoole sebtenced to community service that could be growing food 1 hours a day 7 days a week, producing food, preventing return to bad behavior.

Aloha Paul, well said.

What do you think it would take to get RoundUp (as a first step in banning all pesticides and chemical fertilizers) banned from the island?

Mahalo 🙏

oooops, should say 12 hours a day.

Filipino immigrants used to grow the sugar cane and pineapple here, at $5 an hour.

Now the sugar cane and pineapple are grown in the

Philippines by Filipinos for $3 a day, 12 hours, 7 days a week.

Who gonna grow food here?

Filipinos are doctors, lawyers, Judges, and trades people.

Many temporary farm workers are American and Euro youth looking for travel and experiences, but not enough of them to feed all of us.

So what do we do, plantaion thousands of acres are sitting empty, fallow.

Do we encourge factory farms and ranches?

we each plant small food forests on the land we’re living on

Not many people will become farmers. Even though these farmers are poor, they are very resourceful. They get by.

You always get it almost half right Ken…

The Hawai’ian Kingdom government is fully recognized by over 45 Peace Treaties with Foreign Nations and yet no treaty of annexation is available to review between the usa and Hawai’i…. because it doesn’t exist.

US Military industrial complex and those dependent on their mighty presence are always spewing false information about what is happening to the land and sea.

Put down your bias for a moment read, listen and watch as the multi racial Hawai’ian Kingdom Subjects teach you how to understand the world we live in which is (as you say) indeed POLLUTED but by the usa mismanagement and plundering of our country….

HAWAIIANKINGDOM.ORG describes the facts of land division and ownership as it is according to Law.

Canʻt wait to hear about the “Part” in this system anyone thinks it will work will play.

The best things that we are successful in growing here these days are rusty abandoned cars.

The government to help out local farmers only comes when we have interest in government who supports local farmers. We are buying the majority of our food supply. Sustaining 1.45 million people through local farming is not the answer. Fortunately, businesses are also involved in supplying local foods but bought instead of locally grown.

Aloha John, I’d love to connect. I’m in Kilauea and the recreation of the ahupua’a system, (with appropriate consideration of the present moment in times unique needs) as a model for regenerative land management globally was my reason for coming to this island.

I’d love to see if there’s a way we can work together.

And to everyone else on this thread, I come with humility to learn and to teach. I believe a food, water, energy, shelter, and clothing (basic needs) Kaua’i is possible within a short time period. I’d like to offer my gifts to make this happen, of it’s what the people of Kaua’i want.

Mahalo nui loa for your time and consideration in reading my message.

Aloha

Mahalo to Rev. Dr. Malama, Cydney, Mark Lindsey and Paul for their support and understanding of the real problems, and commenting on some of the solutions to food sovereignty and food security for Hawaii.

To clarify some of the misinformation given by Ken and Peter please let me add the following

• Kamehameha III made the sovereign Hawaiian Kingdom a democratic monarchy where all citizens, regardless of their ethnic background, get one vote; their system was more democratic that what we have now with our electoral college; stating that only indigenous people will have all the power is totally incorrect;

• Every ahupua’a had an “aha council” or “watershed council” where all watershed inhabitants had equal say in the way their natural resources were used and managed; it was the backbone of the ahupua’a system—a watershed community-based resources management system; the system was community-based, not a dictatorship, and if a King, Queen, Ali’i Nui or Konohiki were mean or unfair to the citizens, the maka’ainana or citizens would leave that ahupua’a and go to another one where they would be treated fairly;

• Ken stated, albeit incorrectly, that the “ahupua’a system is only a sweet dream, a Hawaiian sovereignty utopia, founded on no privately owned property, no democratic decision-making, no respect for ethnic or cultural differences”. All of which is patently untrue. In fact, this “sweet dream” was adopted into Oregon State Law in 1993, when the State and all 29 counties adopted “Watershed Councils”, of which Oregon now has over 350 with an annual budget of over $100 million. By comparison, watershed protection in Hawaii, DLNR’s priority program, has a $2 million annual budget;

• Peter stated large-scale food production in Hawaii went out of business years ago, inferring that food can be grown more economically on the USA continent or in Mexico. First, the last time there was large scale food production in Hawaii was the day before Captain Cook arrived in 1778, and again in 1849 when Hawaii fed the “gold rush” in California by sending schooner ships full of potatoes, bananas and cabbages. I think what Peter was referring to is sugar and pineapple going out of business, but these were export crops, not meant for consumption in Hawaii.

• Calculation of what is truly economical depends on using “ecological economic accounting” with no externalities. If you factor in the 50,000 people that died in Gopal, India, from a pesticide factory leak, the Exxon-Valdez oil spill, and the thousands of cancer victims for consuming or being exposed to glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup, food spoilage, etc. from the far away factory farms then growing these contaminated foods is not at all economical.

• Finally John Kalei, please contact me on my draft website (www.koafarms.org) and I will help you make your land abundant with food.

Aloha no e malama pono,

Don “Lalakea” Heacock