HANAPEPE — Today, Salt Pond Beach Park will close for maintenance, shutting down the county’s pandemic-era Shelter-In-Place permitted camping program for the houseless.

This is the last county-owned beach park to shutter, with closures in ‘Anini and Anahola at the end of March, Lucy Wright Park in Waimea in April and Lydgate Park in Wailua at the end of May.

The disassembly of this program utilized by over 200 people was announced in February, and each shutdown has resulted in stress and anxiety for its residents, many unsure of where they will go next.

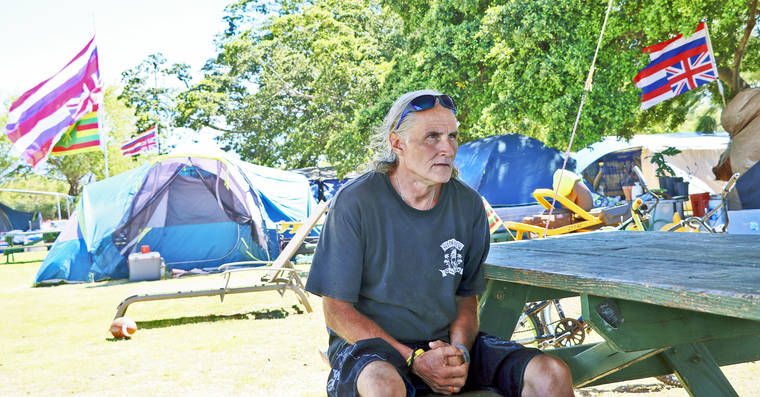

“The weight has been getting heavier,” Kamuela Gomes said Tuesday afternoon. “On a spiritual side, there’s more dark things coming in, more negativity. But that’s natural when you want to do something good.”

Gomes, along with other Salt Pond residents, in February sent a proposal for the conveyance of land to live on while restoring it through agricultural, educational and cultural use to the state and county under the group Holomua, Hawaiian Ahupua‘a Resource Development.

According to the proposal, the group intended to dwell on and maintain an access road for safe ingress and egress, as well as create a native botanical nursery, build tiny homes for Native Hawaiian families, maintain the landscaping, construct a playground for keiki and even put up educational signs.

Nobody has heard back from officials on this proposal.

Residents of the encampment supported the proposal, including those who have lived here prior to the program, including U‘i Kanahele and her brother Lincoln “Bubbles” Niau with his son. Niau mows the lawn and keeps an eye out at the entrance of the beach park by the community garden and smokehouse where he likes to prepare meals.

Before the Shelter-In-Place program, Kanahele would break down her tent every Tuesday for park maintenance, and then put it back up Wednesday.

“It’s hard if you have families,” Kanahele said. “We saw families with five children and the dad works and only have the mom. How is she going to put down a whole 20×20, watch five kids and get out of the park? That was a big issue.”

Under the county’s Shelter-In-Place program, Salt Pond has a limit of 50 permits, county Department of Parks &Recreation Director Patrick Porter said earlier this month.

“However, Salt Pond is different than most of our Shelter-in-Place sites in that there is a significant number of houseless living on state of Hawai‘i Department of Transporation and Department of Land and Natural Resources lands that abut the Salt Pond campsite,” Porter said. “The houseless communities that live on these state lands utilize the restrooms and pavilions in the Salt Pond campgrounds.”

Community members recently set up their own hot-water shower in a sort of protest to a nonprofit’s mobile shower unit that was partially purchased using federal coronavirus funds.

Rather, Gomes would have liked to see that money spent on providing the houseless with tents and other basic needs and rights.

“Once we push the issues and stand up for our Hawaiian rights, we truly see the lawlessness of the state as in where they don’t even follow their own law, such as the precedent set by Martin v. Boise,” Gomes said.

Gomes has gone to court against the county in a civil case in May 2020 using Martin v. Boise as precedent. The U.S. Court of Appeals in 2018 found that a city ordinance in Boise, Idaho, violated the Eighth Amendment of cruel and unusual punishment by citing houseless individuals criminally for sleeping outdoors on public property without alternative shelter.

In February of this year, the city of Boise reached a settlement, ending 12 years of litigation, agreeing that houseless individuals cannot be cited or arrested for sleeping outdoors when no other shelter is available.

And, for many, there’s no other shelter due to the lack of affordable housing on Kaua‘i.

Allen Lee Jr. lives off a fixed income of about $880 per month. According to the organization Fair Market Rent, a two-bedroom apartment here averages about $1,881 per month.

“We just can’t afford a place,” Lee said. “Us that make less than $1,000 a month, we can’t afford to actually get into a place in the first place.”

Recently, the county allocated $2.5 million for a permanent supportive-housing development, similar to its Kealaula on Pua Loke in Lihu‘e, a long-term rental development for families transitioning out of houselessness. This project will combine affordable housing with direct outreach.

Back in January 2020, an official overnight Homeless Point-In-Time Count discovered 424 people either living in shelters or unsheltered. This was a slight decrease from 2019’s houseless count of 443. That’s only an estimate, and oftentimes many are still left uncounted.

And the number may soon grow.

Earlier this month, the Biden administration extended the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention moratorium on evictions to the end of July.

Kopa Akana is concerned that once the moratorium lifts, more people will be struggling with houselessness, and this time around there won’t be any of the five beach parks open for people to stay in.

But, for some, the choice to be houseless is that, a choice.

“You’re a housed community, we’re a houseless community,” Tess Schleihs said. “We have the right to our dreams and our goals, our lifestyles and our sense of being. We are entitled to our right to not being forced out or not having to worry at night if somebody will come take my tent down while I’m sleeping.”

“We know this life. We’ve tried the American dream and, unfortunately … the American dream is just that: a dream,” Mana Geddes added. “We, as Hawaiian people, it is our right to choose what we wish to do on our land.”

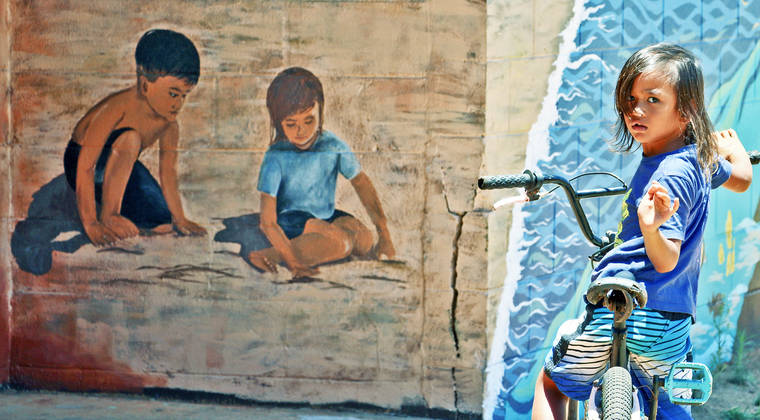

Months ago, artists painted a mural on the bathroom pavilion at Salt Pond telling the origin story of the Hanapepe salt beds. Those staying at the encampment stopped by, some sitting for portraits, including keiki Legend and Indy. The two boys are painted playing in the sand together.

“If you are going to remove them physically here, you should remove them from the wall as well,” Geddes said. “It is a clear representation of what our own government is doing to our own people.”

•••

Sabrina Bodon, public safety and government reporter, can be reached at 245-0441 or sbodon@thegardenisland.com.

Where will they go? Anywhere but there. I guess they’ll have to be bums in Los Angeles. Back to where they’re from. Cannot do that here.

” We’re an entitled community ” Fixed the title for you TGI.

Well if you are so concerned please feel free to go there and give up your house for them along with all your savings if you have any.. Some of us work hard, save hard and get by without thinking we are entitled we just work hard, unlike many

Unfortunately, nationwide liberal policies has shown that being houseless (or homeless) and unemployed is a beneficial career choice for many. Not all want to be in that situation though. But far too many are choosing this new career since you can get free food, free medical, free temporary housing, easy access to drugs, and commit crimes that go unpunished by those in charge. The wage earners no longer see a need to work when everything is free. Those who do work suffer the most in higher taxes for failing social programs that are out of control. We need a solution that involves working for what you receive in the programs (not forced labor camps), and a path to get out of the program. Stop making others who earn pay for those who “want”. Yes, help those is “need”. Not a single politician is willing to tackle this issue with common sense out of fear of being labeled a hater of some kind by the illogical. I hope every person in “need’ in Kauai gets help to get back on their feet (if possible).

424 people homeless…… Please….. If you believe that ridiculous count … Then you simply have been asleep for the past 20 years. The tribes on the mainland have had success helping their own through funds from casinos

Depressing to read the lack of empathy here in these comments. We are all one medical emergency away from financial ruin and homelessness. Check your entitlement, you’re way closer to that “bum” than to Bezos or Zuckerberg.

The “American Dream” got privatized and monetized. Democracy and Capitalism are opposites. We’ve been “taught” they are the same. If we were to nationalize even a small portion of American natural resources, like civilized nations do, Americans would make $80k per year and be able pursue personal happiness, instead of being an Amazon / Uber slave.

Wake up folks before your Corporate Overlords put your children down the coal mines . . . again

They expect the house less to just disappear so the tourist can enjoy our island…screw that…our leaders have failed our community for profit

They supposedly “closed” Lydgate campground over a month ago, and all the homeless did was move to the other side of the rocks, spread out and take over the rest of the park. No rules, no plan…

We want our parks back!!!

I feel sorry for the people who found themselves homeless due to unforeseen illness or job loss. But, those who continue to sit around and not work and complain that the government is not helping, I have not sympathy for. Get of your behinds and do something to better yourself! True Hawaiians don’t sit around and whine! They don’t look for hand outs from people, they are too proud!

Why not endorse the Holomua proposal? Give people land to care for, give people pride in living out their culture and stewardship of the land. Why worry about how people got to be houseless? Let’s do what we can to help people live with dignity and maybe, while we’re at it, do a little something to right the historic wrongs the Hawaiian people suffered.

Removed from the wall also? Seems a little dramatic . The county should make some place inland with ports potties and such where people can camp. Traditionally hawaiians Neva slept at the beach . They believed the sound of waves was not good for sleep, they slept up the valley. Maybe put a homeless camp up away from view .

The park was established for everyone. Not just those who have been squatting there for years. Do not allow camping in the park. You don’t see this problem at poipu Beach park..why? You can’t camp there and the County has to protect their visitors…but not it’s residents.

The last sentence you wrote. You meant that the County is to protect the visitors and not the citizens?

Mr. Stamos; if Hawaiians tradionally neva slept on the beach, then why did they set up a community on the beach in Waimea?