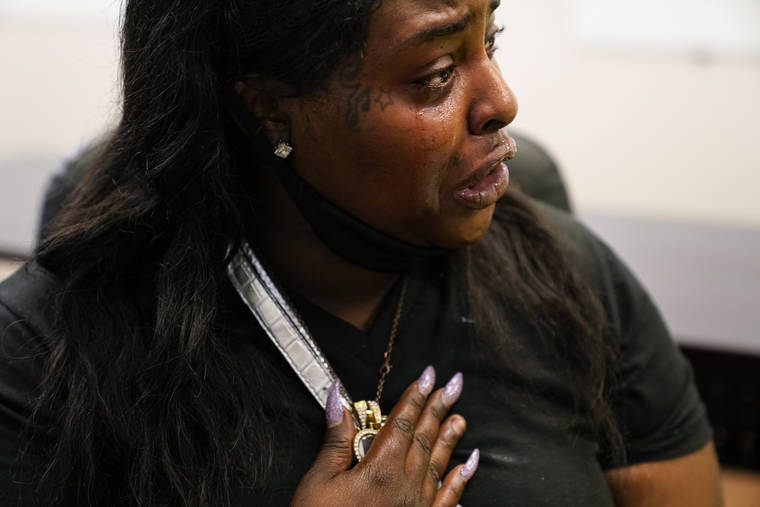

ST. LOUIS — She screamed and cried, banged on the dashboard, begging her husband to drive faster, faster, faster toward her brother lying face-down on his bedroom floor.

Craig Elazer had struggled all his life with anxiety so bad his whole body would shake. But because he was Black, he was seen as unruly, she said, not as a person who needed help. Elazer, 56, started taking drugs to numb his nerves before he was old enough to drive a car.

Now his sister, Michelle Branch, was speeding toward his apartment in an impoverished, predominantly Black neighborhood in north St. Louis. His family had dreaded the day he would die of an overdose for so long that his mother had already paid for his funeral in monthly installments.

It was September, and as the COVID-19 pandemic intensified America’s addiction crisis in nearly every corner of the country, many Black neighborhoods like this one suffered most acutely. The portrait of the nation’s opioid epidemic has long been painted as a rural white affliction, but the demographics have been shifting for years as deaths surged among Black Americans. The pandemic hastened the trend by further flooding the streets with fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, in communities with scant resources to deal with addiction.

In the city of St. Louis, deaths among Black people increased last year at three times the rate of whites, skyrocketing more than 33% in a year.

Dr. Kanika Turner, a local physician leading efforts to contain the crisis, describes the soaring death rate as a civil rights issue as pressing as any other. The communities being hit hardest are those that were devastated by the war on drugs that demonized Black drug users and hollowed out neighborhoods by sending Black men to prison instead of treatment, she said.

Last year, George Floyd died in Minneapolis under a police officer’s knee. He had fentanyl in his system and some of the officer’s defenders tried to blame the drugs for his death. The world exploded in rage.

“That incident on top of the pandemic rocked the boat and shook all of us. It ripped the Band-Aid off a wound that has always been there,” said Turner. “We’re undoing history of damage, history of trauma, history of racism.”

Harsh sentencing laws passed in the 1980s were far more brutal on crack cocaine users, who were more likely to be Black, than they were for powder cocaine users, who were more likely to be white.

Many who work with Black drug users say that addiction was not widely accepted as a public health crisis — with a focus on treatment instead of incarceration — until the current opioid epidemic began in the late 1990s when addiction to prescription opioids took root in struggling, predominately-white communities.

When white people started dying and people on TV talked about how they needed to be saved from this public health tragedy, Branch wondered where they’d been when her brother was swirling into addiction.

She can’t count the number of times her brother tried to get sober.

Even today, Black people are more likely to be in jail for drug crimes and less likely to access treatment.

White people are far more likely than Black patients to receive the medicine buprenorphine, which has been found to greatly reduce the risk of overdose death. Black people instead tend to be steered toward methadone, distributed in highly regulated programs that often require standing in line daily before dawn.

Over the last several years, the drug supply has grown so unpredictable that people overdosing have multiple drugs in their system: dangerous cocktails of fentanyl, a depressant, and stimulants like cocaine and methamphetamine.

Deaths began surging among Black Americans. The pandemic intensified that trend by further flooding the streets with fentanyl.

Other cities saw a similar pattern.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that more than 92,000 Americans died of overdose in the 12-month span ending in November, the highest number ever recorded. That CDC data is not broken down by race.

But researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles, analyzed emergency medical calls nationwide and found an overall increase of 42% in overdose deaths in 2020. The largest increase was for Black people, with a spike of more than 50%.

Craig Elazer’s family had dreaded his death for decades.

He was a bright child: By third grade, he could read as well as a sixth grader.

But he was anxious and jittery. Had he been treated, Branch believes he would be alive.

“But they didn’t catch hyperactivity or bipolar back then, especially not in little Black kids. We were just unruly, undisciplined, this much removed from being an animal,” Branch said.

He started drinking when he was 12, and progressed to drugs.

Their mother got sick with pancreatic cancer, but she lingered for years. Her family believed she was holding on out of fear of what would happen to her son.

She died still worried about him.

He was in and out of jail, mostly for petty offenses. Several years ago, an acquaintance alleged he sexually assaulted her while using drugs and alcohol. His lawyer told them the odds were against him as a Black man accused of assaulting a white woman, Branch said. He pleaded guilty and spent three years in prison.

He was released in May 2020, as the pandemic bore down.

He couldn’t find a job. There were no recovery meetings in-person. He was alone most of the time.

One night they couldn’t reach him. His cousin looked through the mail slot and saw him lying there.

Branch sped toward his apartment, and was hysterical by the time she arrived.

They tried to convince her not to go inside, but she wanted to see him.

As Branch looked down at his body, she felt calm come over her.

“Society failed him,” she said. “And I had a sense that he’d finally been set free.”