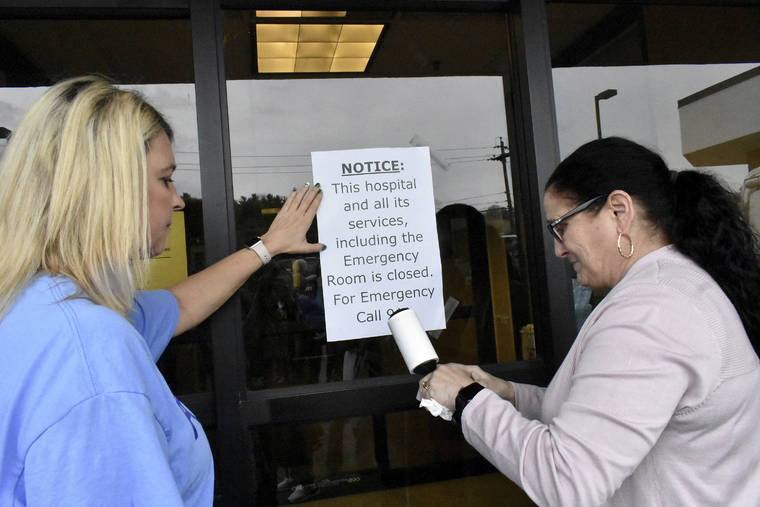

CARROLLTON, Ala. — As the coronavirus spread across the United States, workers at the lone hospital in one Alabama county turned off beeping monitors for good and padlocked the doors, making it one of the latest in a string of nearly 200 rural hospitals to close nationwide.

Now Joe Cunningham is more worried than ever about getting care for his wife, Polly, a dialysis patient whose health is fragile. The nearest hospital is about 30 miles away, he said, and that’s too far since COVID-19 already has been confirmed in sparsely populated Pickens County, on the Mississippi state line.

Cunningham is trusting God, but he’s also worried the virus will worsen in his community, endangering his wife without a hospital nearby.

“It can still find its way here,” said Cunningham, 73.

The pandemic erupted at an awful time for communities trying to fill health care gaps following the closure of 170 rural hospitals across the nation in the last 15 years. 2019 was the worst year yet, with 19 closures, and eight more have shut down since Jan. 1, according to the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina.

While the nation’s coronavirus hot spots so far have been big cities like New York and New Orleans, officials fear inadequate testing and the lack of medical resources linked to hospital failures will catch up with smaller population centers.

The reasons for the closures vary, but experts and administrators cite factors including declining rural populations, rising medical costs, insufficient Medicare reimbursements, large numbers of uninsured patients, state decisions against Medicaid expansion and mismanagement. About 60% of the counties and towns that have lost hospitals are in the South, an analysis by the Sheps Center showed.

Other communities are trying to keep hundreds of endangered hospitals afloat as resources are stretched thinner than ever and moneymaking services like elective surgeries are curtailed during the outbreak.

“It’s a scary time to be thinking about losing a hospital when you’ve got a pandemic going on,” said Scott Graham, chief executive officer of Three Rivers and North Valley Hospitals in central Washington. The hospitals serve about 26,000 people in a wide-open area that Graham describes as so remote it’s more frontier than rural.

In North Conway, New Hampshire, a physician at the 25-bed Memorial Hospital already is among the county’s seven confirmed cases of coronavirus, said CEO Art Mathisen. The hospital is preparing for the worst as it tries to triple the number of beds and spends upward of $100,000 on rooms with air flow aimed at limiting the spread of contagions, he said.

About 15% of the U.S. population, or more than 46 million people, lives in rural areas, according to the Census Bureau. They are more likely than urban dwellers to die from chronic respiratory illnesses, heart disease and other problems that put people more at risk for COVID-19, the illness caused by the virus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For most people, the coronavirus causes mild or moderate symptoms, such as fever and cough that clear up in two to three weeks. For some, especially older adults and people with existing health problems, it can cause more severe illness, including pneumonia, and death.

In West Virginia, where no city has a population of more than 50,000 and 20% of residents are senior citizens, frustration has mounted over two recent hospital closings that forced patients to seek help farther away. A tentative purchase deal was announced Wednesday for a third hospital that had said it would shut down sometime in April. There has been talk but no immediate action to open new facilities to deal with coronavirus cases in one of the unhealthiest states.

“We certainly need our local hospital. We need the beds. We need the equipment, and we need it locally,” said Michael Angelucci, a state lawmaker who operates an ambulance service in rural Fairmont, West Virginia, where a hospital closed this month.

The pandemic could actually hasten more rural hospital closures, said Michael Topchik of the Maine-based Chartis Center for Rural Health. He co-authored a study released in February that found about 450 rural hospitals were vulnerable to shutting down.

Most rural hospitals make money on emergency room care and elective procedures, which are on hold as health care workers try to ration masks and other protective gear in anticipation of COVID-19 infections, he said.

“Our study predicts the worse is yet to come if something’s not done to stabilize the safety net,” he said.

In northern Missouri, Sullivan County Memorial Hospital’s chief executive, Tony Keene, said that on top of the recent drop in revenue linked to reduced services, he has been pumping money into preparation for a possible outbreak in the rural area by the Iowa border where the hospital is.

“We need an infusion of cash, like now,” Keene said. “If we go a couple more weeks, we are going to have to make very serious decisions on whether we pay our vendors or pay our people.”

The $2.2 trillion coronavirus package approved by Congress last week includes $100 billion for hospitals, but it’s unclear how much of that will go toward rural health care centers.

As Pickens County Medical Center prepared to close on March 6, Mayor Mickey Walker organized a protest outside the public hospital that drew around 70 people — a big crowd in a town of only 950 people. The facility shut down anyway.

A building beside the shuttered, tan-brick hospital houses medical offices, including the dialysis clinic that treats Joe Cunningham’s wife, but Walker said that’s not enough. The old folks Walker talks to through church are getting more worried by the day about the new virus.

“Everybody’s just real panicky,” Walker said. “We have all this virus stuff going on, and we don’t have a hospital to go to.”

———

This story has been corrected to show the name of the Maine group is the Chartis Center for Rural Health, not the Charter Center for Rural Health.

———

Associated Press writers Summer Ballentine in Jefferson City, Missouri; John Raby in Charleston, West Virginia; Michael Casey in Concord, New Hampshire; Kim Chandler in Montgomery, Alabama; Amy Forliti in Minneapolis; and Gillian Flaccus in Portland, Oregon, contributed to this report.

———

Follow AP coverage of the virus outbreak at https://apnews.com/VirusOutbreak and https://apnews.com/UnderstandingtheOutbreak