BANGKOK — News that a new virus that has afflicted hundreds of people in central China can spread between humans has rattled financial markets and raised concern it might wallop the economy just as it might be regaining momentum.

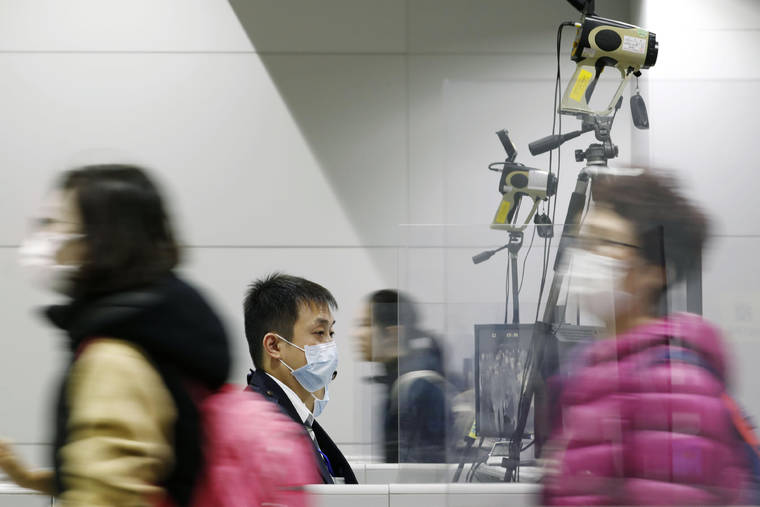

Health authorities across Asia have been stepping up surveillance and other precautions to prevent a repeat of the disruptions and deaths during the 2003 SARS crisis, which caused $40 billion to $50 billion in losses from reduced travel and spending.

The first cases of what has been identified as a novel coronavirus were linked to a seafood market in Wuhan, suggesting animal-to-human transmission, but it now is also thought to be spread between people. As of Wednesday, more than 500 people were confirmed infected and 17 had died from the illness, which can cause pneumonia and other severe respiratory symptoms.

A retreat in financial markets on Tuesday was followed by a rebound on Wednesday, as investors snapped up bargains. Share benchmarks were mostly higher both in Asia, Europe and the U.S.

While the new virus appears much less dangerous than SARS, “the most significant Asia risk could lie ahead as the regional peak travel season takes hold, which could multiply the disease diffusion,” said Stephen Innes, chief Asian strategist for AxiCorp. “So, while the risk is returning to the market, the lights might not turn green until we move through the Lunar New Year travel season to better gauge the coronavirus dispersion.”

The 2003 outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in China, along with cases of a deadly form of bird flu, resulted in widespread quarantine measures in many Chinese cities and in Hong Kong. More than 8,000 people fell sick and just under 800 people died, a mortality rate of under 10%.

While the ordinary flu kills hundreds of thousands of people each year, such new diseases raise alarm due to the uncertainties over how deadly they might be and how they might spread. That’s especially true during the annual mass travel of the Lunar New Year festival, which begins this week.

“The cost to the global economy can be quite staggering in negative GDP terms if this outbreak reaches epidemic proportions,” Innes said in a report.

In China, health officials stepped up screening for fevers. “We ask the public to avoid crowds and minimize the public gatherings to reduce the possibility of cross infection,” Li Bin, deputy director of the National Health Commission, said Wednesday.

As with SARS, the impact of the disease is likely to fall heaviest on specific industries, such as hotels and airlines, railways, casinos and other leisure businesses and retailers, analysts said.

In a statement on its website Wednesday, Shanghai Disney Resort said it was operating normally but understood if some guests wished to change their travel plans. The park said it would let guests reschedule their visits or refund their money.

China’s Civil Aviation Administration called on airlines to offer free refunds for tickets in or out of Wuhan.

“If the pneumonia couldn’t be contained in the short term, we expect China’s retail sales, tourism, hotel & catering, travel activities likely to be hit, especially in the first and second quarters,” said Ning Zhang of UBS. Government efforts to offset the shock would help, but growth will likely rebound less than earlier forecast, Zhang said.

The outbreak is a boon, meanwhile, for pharmaceutical companies and makers of protective masks and other medical gear.

As of Jan. 17, the World Health Organization had not recommended any international restrictions on travel but urged local authorities to work with the travel industry to help prevent the disease from spreading while warning travelers who fall ill to seek medical attention.

The illness is yet another blow for Hong Kong, whose economy is reeling from months of often violent anti-government protests. The wider concern is China, where the economy grew at a 30-year low 6.1% annual pace in 2019. An interim trade pact between Beijing and Washington had raised hopes that some pressure from tensions between the two biggest economies might ease, and the latest data have showed signs of improved demand for exports.

The virus outbreak raises the risk such optimism might be premature.

“We expect increased downward pressure on China’s growth, particularly in the services sector,” said Ting Lu and other analysts at Nomura in Hong Kong, who based their projections on the spread of the SARS virus.

The growing number of global travelers has contributed to the spread of various diseases in recent years, including Middle East respiratory syndrome, the Ebola and Zika viruses, the plague, measles and other highly contagious illnesses.

The World Economic Forum estimates that pandemics — cross-border outbreaks like the flu that killed 50 million people a century ago — have the potential to cause an $570 billion in annual economic losses.

The 2014-16 Ebola virus epidemic caused losses amounting to over $2.2 billion, according to the World Bank. That includes a 40% decrease in the number of working Liberians at the height of the crisis, lower exports and harvests, and costs for combating the disease.

Apart from the human tragedy, such crises gobble up resources needed for other government spending, exacting a harsh toll on the poorest economies. In Africa, the loss of health care workers to Ebola resulted in thousands more deaths of mothers and babies, hindered work on other diseases such as preventing and treating malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, reduced vaccination rates and fewer surgeries, the World Bank said in a report.

Many survivors, meanwhile, suffer from lingering effects of the illnesses and the powerful drugs used to save their lives, becoming more vulnerable to hunger and other risks.

At the same time, increasingly sophisticated tools for collecting data and analyzing are aiding efforts to prepare for and cope with severe disease outbreaks.

In 2016, the World Bank set up a $500 million rapid response insurance fund, working with the WHO and insurance companies, to combat pandemics in developing countries. The fund uses “cat bonds,” or catastrophe bonds, whose principal will be lost if the funds are needed to help deal with an outbreak. Private insurers have followed with products of their own meant to hedge against risks from such disasters.