WELLINGTON, New Zealand — Samoa’s main streets were eerily quiet on Thursday as the government stepped up efforts to curb a measles epidemic that has killed 62 people.

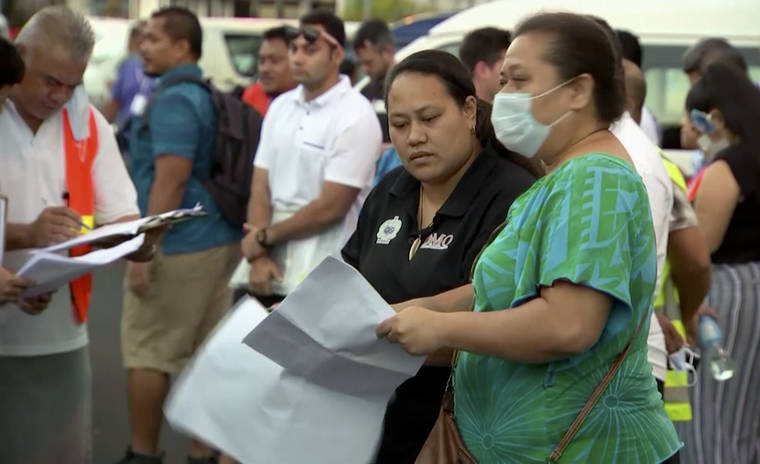

The government told most public and private workers to stay home on Thursday and Friday and shut down roads to nonessential vehicles as teams began going door-to-door to administer vaccines.

Families in the Pacific island nation were asked to hang red flags from their houses if they needed to be vaccinated.

Most of those who have died from the virus are young, with 54 deaths among children aged 4 or younger.

The Samoa Observer newspaper said the normally bustling capital Apia was a ghost town on Thursday, with only birds nesting in the rooftops and stray dogs roaming the streets.

Prime Minister Tuilaepa Sailele Malielegaoi told reporters the vaccine drive was unprecedented in the nation’s history.

He said one challenge was that a lot of people hadn’t considered that measles could be deadly.

“They seem to take a kind of lackadaisical attitude to all the warnings that we had issued through the television and also through the radio,” he said.

Another challenge, he said, was that others had been seeking help from traditional healers, who had been successfully treating tropical diseases in Samoa for some 4,000 years.

“Some of our people pay a visit to traditional healers thinking that measles is a typical tropical disease, which it is not,” the prime minister said.

Samoan authorities believe the virus was first spread by a traveler from New Zealand.

The nation declared a national emergency last month and mandated that all 200,000 people get vaccinated. The government has also closed all schools and banned children from public gatherings.

According to the government, more than 4,000 people have contracted the disease since the outbreak began and 172 people remain in hospitals, including 19 children in critical condition.

Figures from the World Health Organization and UNICEF indicate that fewer than 30% of Samoan infants were immunized last year. That low rate was exacerbated by a medical mishap that killed two babies who were administered a vaccine that had been incorrectly mixed, causing wider delays and distrust in the vaccination program.