KALAHEO — The bright green rose-ringed parakeets stir thoughts of jungle adventures and tropical getaways, but the exotic-looking birds are taking a bite out of Kauai.

Quite literally.

They’re shredding through lychee and mango, papaya and corn, guava and other crops. They leave messes on unsuspecting cars in parking lots. If you happen to be hitting up happy hour near a tree when they’re roosting, it’ll be so loud you probably won’t be able to enjoy your drink.

These birds present problems, so much so that in 2018 the Hawaii Legislature dedicated money to study and manage the Kauai population.

The birds, which were released in the 1960s on Kauai, are on Hawaii Island and on Oahu in much smaller numbers. That makes Kauai a testing ground for strategies to control the species that’s rapidly expanding.

On Monday afternoon, residents got to meet one of the researchers funded through the U.S. Department of Agriculture to help with the job — Jane Anderson, assistant professor of research with the Cesar Klebert Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M University.

About 60 people gathered at the National Tropical Botanical Garden to hear Anderson’s lunchtime talk.

“We’re excited there are local people here to work with and we’re happy to collaborate,” Anderson said after introducing her specialty — a focus on invasive species that are “cute” or have the reputation of being adorable, species like monkeys and parakeets.

Anderson has experience working with invasive monkeys in Florida and finding ways to balance public opinion with preservation of endemic species and ecosystems.

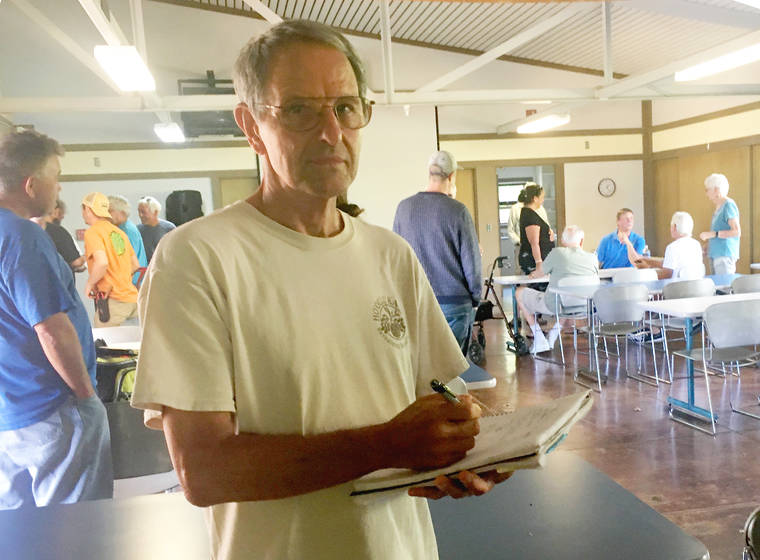

Everyone at the meeting wanted to help and swarmed Anderson with stories and suggestions.

“I think it’s a great start,” said Juan Myers, an Omao man who considers himself a hobby farmer, but sells avocados around the island. “It’s really good to bring everyone together.”

Myers has been taking losses on his small farm for about five years. Right now, the birds are going for the papayas at his house.

“It used to be that they waited until the papayas got a bit yellow, so we’d have a chance (at harvesting), but now they eat them as the green ones. They never ripen,” he said. “It’s an interesting story because parakeets have no predators here, they’ve gone nuts.”

Anderson’s been on-island for about two weeks. She said she’s here for two reasons — to understand the population and to understand the movement of that population.

Some said the time for a population study has passed.

A 2018 count of the birds put Kauai’s population at about 7,000, Oahu’s population at about 4,600 and the Hawaii Island population is estimated at about 500.

Lowering the population is imperative, Anderson agreed. She and her team are working on management strategies to try and come up with some good ideas on control.

Many at the meeting said they already shoot the birds — Myers said he’s recently invested in a pellet gun to try and dissuade them from his farm.

That’s an effective management strategy, according to Anderson, but it has to be used strategically — for instance, if the birds’ roosting spot is disturbed, they’ll move and re-disperse around the island.

Also, those roosting spots include Kukui Grove Center and other public places where that method of control would be dangerous.

The team is also testing a type of bird feeder that would allow only rose-ringed parakeets to eat and could house chemicals to render the birds sterile. Anderson said that method would be thoroughly tested without using chemicals.

“I’m really looking to connect with some hunters and that group,” Anderson said. “But this is what we want to do on Kauai, test different management systems.”

For more information, call the Kauai contact for the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources at 274-3471 or reach out to Kauai Invasive Species Committee by email at kisc@hawaii.edu.

If you use the logic used by the feral cat people, these are “community parakeets” and should be fed every day. And using the logic of animal balance, we should catch these birds, remove their tiny gonads, then release them again. Good to see this scientist talking about hunters! Shooting these birds unfortunately is the best approach now. Maybe she can talk some sense into KHS about lowering the feral cat population.

These are the FERAL CAT estimates (made over varying periods of time) that are difficult to confirm: Oahu – 350,000 (said to be an underestimate); Maui – 150,000; Big Island – 500,000; Kauai – 15,500. Imagine that. 350,000 feral cats on Oahu along, about 1 to every 3 people on-island. Those numbers are profoundly stupid. Feral cats should be hunted like open season.

The state needs to do something ASAP. Sterilization is not the answer. We need to kill and remove the population entirely from the island. These birds live a long time. “Life Expectancy. In the wild, Indian ringnecks have been documented to live up to 50 years, with 20 to 30 being more the norm. Caged ringnecks typically live between 15 and 25 years.” Do they really expect us to wait 20-50 years ?

Wow, To those who messaged, killing wildlife is NOT the answer. If you do your homework you will know that most of the wildlife here is not native. Almost all came from elsewhere. Finding solutions for sterilization and or moving them to other areas is the humane way. Anything else is totally unacceptable and will gain international attention for cruelty!

I would like to see you own a business where these birds eat half of your saleable product. Time to issue a pellet rifle to every capable and willing person on the island. OPEN SEASON, BABY!

How about solving 2 problems at once? Trap, spay/neuter feral cats and release them where the parakeet populations are.

Whatever works. They have got to be eliminated somehow

“Totally unacceptable” F’reals??

Actually, looks like eradication is quite acceptable to lots of reasonable folks, while the invasive parakeets are “totally acceptable.”

Hunting or trapping is quick, humane and effective. Get ’em gone.

These beautiful but harmful pests have infested my neighborhood and eaten fruit crops for the the past decade. The state authorities have been aware of the exploding problem for many years. What I don’t understand is why only now they seem to be ready to try doing something about it. It’s too late. They are established here on Kauai in the thousands.