Kathryn Johnson, a trailblazing reporter for The Associated Press whose intrepid coverage of the civil rights movement and other major stories led to a string of legendary scoops, died Wednesday. She was 93.

Her niece, Rebecca Winters, said Johnson died Wednesday morning in Atlanta. Johnson was the only journalist allowed inside Martin Luther King Jr.’s home the day he was assassinated. When Gov. George Wallace blocked black students from entering the University of Alabama, she sneaked in to cover his confrontation with federal officials. She scored exclusive interviews with 2nd Lt. William L. Calley Jr. before he was convicted of his role in the My Lai massacre.

“I was never ambitious, really, anxious to make money …,” she told an interviewer for an AP oral history project in 2007. Johnson said she didn’t want to be bored and added, “in most of my career, I really wasn’t.”

That career spanned a half-century, from the era of reporters racing each other to pay phones to the birth of 24-hour cable television news.

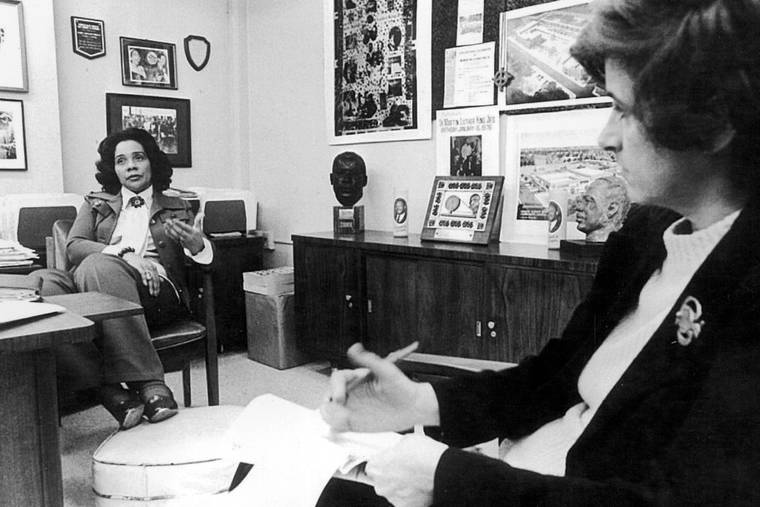

She began covering King when he was a little-known Baptist preacher from Atlanta. She had also written about his wife, Coretta, who was a talented singer.

The evening of April 4, 1968, Johnson and a date were on their way to the movies when news of the assassination came over the radio.

When she arrived at the King house, two reporters were chatting with a police officer on the porch. The front door opened, and Johnson could see Coretta Scott King in a pink nightgown, standing in the hall. “She spotted me and said, ‘Let Kathryn in,’” she recalled.

Johnson was at the home every day, giving the AP several scoops — including an 11-hour beat over archrival United Press International on the funeral arrangements.

She later wrote the book “My Time With the Kings,” which was published in 2016 and recollected her time covering the civil rights movement.

“Kathryn Johnson was essential reading on one of the most important stories of the 20th century, and she did it by being at the center of the action, close to the most important newsmakers,” AP Executive Editor Sally Buzbee said.

Born in Columbus, Georgia, Johnson graduated from Agnes Scott College, a private, all-woman school in Decatur, Georgia, in 1947. In December of that year, she dropped by the local AP office looking for a job; she was offered a secretarial position.

“I think she was an unknown pioneer in that field,” Winters said.

Twelve years later, after the American Newspaper Guild interceded, Johnson was finally given a writing job. She said she got the civil rights beat because the men “did not want to cover a black movement.”

“When my aunt was interested in this young preacher named Martin Luther King, the men in journalism didn’t want anything to do with a black man and interviewing him,” Winters said. “She was just enthralled with the man, before he was famous.”

Her first big story was Charlayne Hunter’s integration of the University of Georgia in January 1961. Still youthful looking at 34, she impersonated a student to get close to Hunter.

In June 1963, Johnson was in Tuscaloosa, where Wallace blocked the entrance of the University of Alabama’s Foster Auditorium to black students. She and the other reporters were ushered into a large room and locked in. She went to the door and told the young patrolman that she had to use the “ladies room.”

She went to the front doorway where Wallace and Deputy U.S. Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach were talking, and slipped under a large table set up for microphones. She was just a couple of feet from Wallace’s legs.

For Christmas in 1969, Johnson was asked to interview the wives of Navy men missing in action or held captive in North Vietnam. Among them was Navy Capt. Jeremiah Denton, among the first prisoners of war to return home in 1973.

“When my father came home, she became very close to our family and covered my father,” Denton’s daughter, Mary Denton Lewis, recalled. “He trusted Kathryn more than any other reporter because of her close relationship with my mom.”

Denton retired with the rank of Rear Admiral and later served in the U.S. Senate.

From late 1970 to early 1971, she covered the hearings and courts-martial stemming from the March 1968 massacre of Vietnamese civilians at the village of My Lai, and developed a rapport with Calley, the officer charged with the slaughter.

Before the verdict, she persuaded Calley to give her two interviews: One for an acquittal, another for a conviction.

She left the AP in 1979 to take an associate editor’s position at U.S. News & World Report. In 1988, she joined CNN, working there full time until 1999.

———

Associated Press writers Bernard McGhee and Jeff Martin in Atlanta contributed to this report.