LIHUE — A new documentary by Kauai native, former journalist and Emmy Award-winning documentary filmmaker Stephanie J. Castillo will launch Saturday with a video shoot of researchers searching for the Hanapepe site where 16 Filipino sugarcane workers were believed to have been buried in an unmarked grave in 1924.

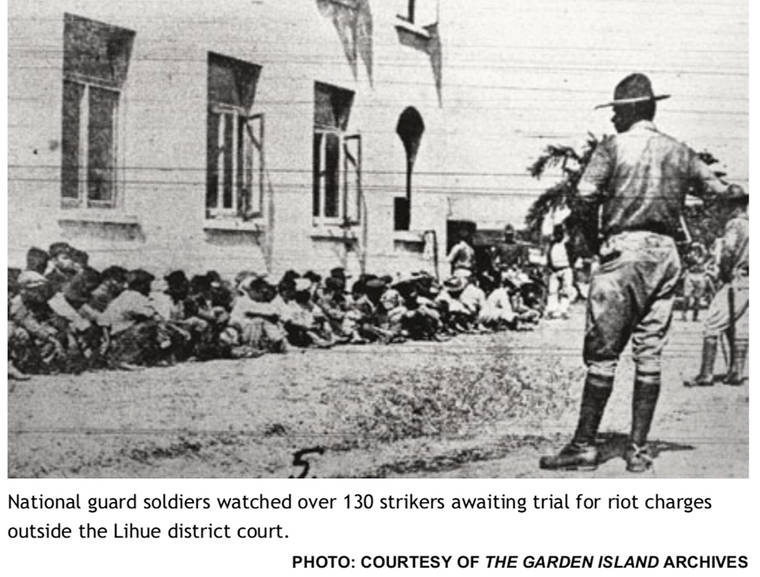

The incident involved a melee that broke out that year on Sept. 9 when Visayan striking workers battled local police and deputized hunters in what’s been called the “Hanapepe War.” Sixteen workers and four police deputies were killed that day. More than 100 other workers involved in the incident were jailed and tried.

Castillo returned to her home island in July after six years on the mainland where she worked on her last documentary film about a New York City jazz great. Her ‘Olena Productions company previously based in Honolulu for 30 years, where she made more than 10 award-winning documentary films.

The story of the Hanapepe massacre peaked her interest when an article appeared in the local newspaper announcing a research team from the Kauai Chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society working to find the grave of the Filipino sugar workers killed and to identify those buried in the mass grave. The group plans to present their findings in July at a biennial conference of FANHS chapters meeting in Waikiki.

Castillo met with the group to propose a documentary film called “The Hanapepe Massacre Mystery” made for PBS broadcast, and will bring a Honolulu documentary film crew on Saturday to document the researchers examining the suspected grave site to try to confirm the Filipino cemetery as the location and the actual place were 16 coffins were buried.

On Oct. 19, a ground-penetrating radar machine will be used to help confirm this indeed is the grave site. Such equipment is used in construction to locate subsurface materials, such as bones and artifacts. Digging up or disturbing graves is not allowed in Hawaii.

A cement marker appears to be near the site, they say, but it only shows a date of birth and the death date of Sept. 9, 1924, without naming a person.

“We think this marker was placed by a loved one who wanted to mark the site. We don’t know when it was placed or who placed it. Another mystery,” said Catherine Lo of Kukuiula, one of the researchers.

The story that appeared in The Garden Island newspaper Sept. 9, 2019, has created local interest. Emails, phone calls and text messages began to fly when researcher Mike Miranda sent the story in for the massacre’s 95th anniversary.

“Most of us of Kauai have heard of this massacre, but the complete story with all the complex details has never been told,” said Miranda, of Lihue. “It’s time it was, and we’re grateful that Stephanie has decided to take this on.”

The Kauai FANHS chapter, headed by Miranda, is also hoping to unearth what led to the battle and how it could have been prevented. They have been working for about a year to understand the event.

The battle involved striking Filipino plantation workers from the Makaweli Plantation in Hanapepe and Kauai sheriffs that included deputized hunters.

“There were so many accounts of what happened and how it happened, right after 1924. We may never get the true story, since those involved were killed, deported or arrested, and many who survived have since passed,” Miranda said.

No photos exist of the melee on Sept. 9, 1924, but photos were taken by The Garden Island newspaper and the Honolulu Star-Bulletin of the days after and the aftermath which involved the jailing and trial of the surviving strikers involved in the “battle.”

“The most consistent account of September 9 that we have found so far is that the striking workers were accused of kidnapping or assaulting two workers who crossed the picket line. With tensions already high, a loud noise that may or may not have been gunfire triggered the fighting,” he said.

”Language barriers and the strong anti-union sentiment of the 1920s made it even more difficult for both sides to diffuse the situation.”

Building on past research and available literature, the group looks to analyze what led to the battle, how it could have been prevented, and its legacy. The FANHS-HI Chapter Kauai contingent includes Miranda, Lo, Karl Lo, Raymond Catania, Fern Holland and Dale Shimamura.

The team hopes to cap their work by locating the true resting places of the sheriffs and plantation workers killed, and placing proper markers on their graves.

“The Hanapepe Massacre already has a monument in the public park near the Hanapepe fire station,” Miranda said. “But marking the graves, we feel, would bring closure for the descendants of those who passed in this incident. It would also be a symbol of the early struggles in breaking down cultural barriers and the importance of us learning to coexist today.”

The idea to launch more in-depth research into the event sparked from an oral history project by Kauai man Chad Taniguchi, who interviewed witnesses in 1977 while studying at University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Miranda also studied the event while going to UH Manoa.

“For me, the Hanapepe Massacre was not part of any history class in public schools. I was a junior at UH Manoa when I finally learned about the Hanapepe Massacre,” Miranda said. “Our team is relying on data that’s been out there, but the dots have not been connected. Any information that people think can be useful is welcome.”

Silent voices are a glimmer of hope that we shall learn from those unheard.

It might have been retaliation for having too many all-night barking pit bulls and abandoned cars on their property.

Do you guys edit your articles?

Jeepers!!

Now days going on strike means losing a few paychecks..

Back then going on strike could mean death.

That’s hardcore.

Even in those days, u.s. pretending to be in charge, as now! mAhalo for those that have researched and Due Diligence collections of this event and proper headstone placement.

FYI, i see a huge connection with how the TMT is handled and the pretenders no longer able to pull more fraud and corruption out of their warring mentality and killing machinery coffers! Look up to the sky every day! A reminder that THIS worldwide phenomena has not made the weather reports or news item! Why?