There is a modest home near the top of the Kapaa bypass road with a mailbox in front that says “The Judge.”

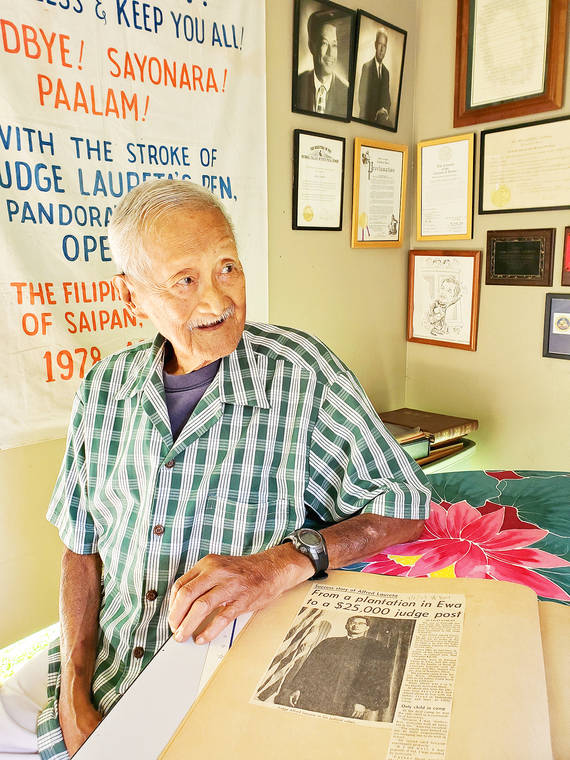

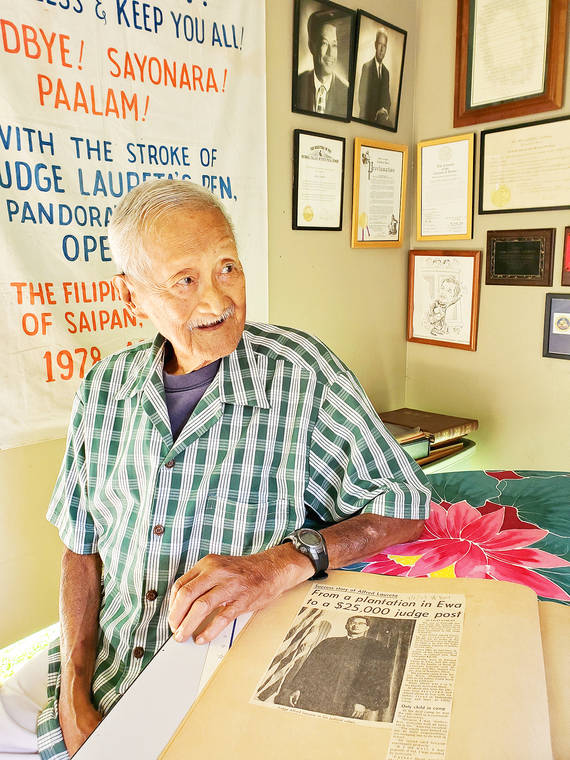

Attached to the side of the house, near a neatly kept vegetable garden, is a roofed-in sitting area with three walls and a table in the middle, and the three walls are covered in an extraordinary lifetime’s worth of plaques, certificates and diplomas.

Retired U.S. District Court Judge Alfred Laureta sat there on Friday afternoon for an interview with The Garden Island, while the sons and daughters of his daughter’s daughter played in the yard.

Before he attended one of the best universities in the country or served on the governor’s cabinet or worked on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, before he was appointed by the president of the United States to serve as a federal judge on a tiny island in the South Pacific, even before he had 17 great-grandchildren, Alfred Laureta was a poor Filipino boy in a plantation camp.

He was born 95 years ago at Banana Camp in Ewa, Oahu, the only son of Filipino immigrants who came to Hawaii so his father could work as a laborer on the plantation. His parents’ relative lack of formal education did not stop Laureta from excelling scholastically, and from an early age those around him took notice.

Laureta’s parents were divorced when he was very young and he spent his formative years with his father, who then lived in a community in the camp that was composed entirely of bachelors.

“Because I was ‘motherless,’ everyone took an interest in me. The single men looked on me as their responsibility, encouraging me to do well in school,” Laureta told a newspaper reporter in 1967, shortly after he had been appointed to be a judge in Hawaii’s First Circuit Court, Oahu. “My report card became community property.”

It would not be the last time Laureta’s education bore the weight of his people. It became a pattern in his life, and he now attributes his success to the people in his life who put the development of his mind ahead of their own financial or practical concerns.

Laureta finished high school and worked his way through college at the University of Hawaii at Mano, paying for tuition with a summer job in a pineapple cannery. He went on to graduate with a bachelor’s degree, with dreams of going to law school. But just as he was ready to abandon the idea of becoming a lawyer, Laureta said the community once again took an interest in him.

“A Filipino priest, his name was Osmundo Calip, he went on his own and convinced the University of Fordham to give me a scholarship,” Laureta said.

It was a three-year scholarship to a private college in New York City, widely recognized as one of the most prestigious and selective in the nation. Fordham University alumni include U.S. senators, Academy Award-winning actors, two former CIA directors and the current U.S. president, and its law school ranks among the best in the world.

In the late 1940s, Laureta got accepted. And it was a big deal, he said, not just on a personal level, but also because of what he represented.

“Very few Filipinos got into higher education because the parents were all laborers in the plantation,” Laureta said, remembering his days at UH when he was one of just a handful of Filipino students. “They did not have the money to send most of the kids. So the few Filipinos that could send their kids to go to college were very rare.”

The lack of college-educated people in the Filipino population translated directly to their socioeconomic status, Laureta explained.

“At that time in the history of Hawaii, there were no professional Filipinos in any kind of business,” he said, adding it “was due to the fact that in order for you to practice in a profession, you had to graduate from a mainland school.”

After he was admitted to Fordham, Laureta said he got a second scholarship from an unusual source — a Japanese organization that, until then, had provided funding for causes exclusively within the their ethnic community.

“One of the judges on that foundation convinced that foundation, ‘look, we are not only a Japanese organization, but we are part of Hawaii. We are here to help all Hawaiians, including Filipinos,’” Laureta said. “So, I was the first non-Japanese recipient of assets from their foundation, and I went to law school with that.”

So when Laureta embarked on the next stage of his education, leaving Oahu for the first time and moving to the Bronx — one of New York City’s five boroughs — he shouldered a heavy responsibility. It was not lost on him.

“I told them the only condition you can impose upon me, I will come back to Hawaii to practice law,” he said. “My condition was, I will accept the scholarship, but I promise I will come back to Hawaii.”

Shortly before graduating, he married Evelyn Reantillo, a nursing student at a neighboring university in the city, whose parents, Laureta said, “bribed me with everything they could to try to convince me to stay in New York.”

Reantillo’s family must have seemed pretty well off to Laureta. Her father held a master’s degree in engineering from Columbia University, an Ivy League school in New York, according to a 1963 Honolulu Star-Bulletin article. Laureta, meanwhile, was living on a $1,000 annual scholarship stipend and the money he earned at his summer job as an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center.

“They tried to get me to stay. I know they promised me all kinds of things,” Laureta said. “But I told them, ‘I have a commitment.’”

Laureta returned to Oahu in 1953. He had a wife and a law degree but no job and no license to practice his profession. It would be months until the next scheduled bar exam, time Laureta knew he would need to spend almost exclusively studying.

Again, a path to his future was smoothed by people who took an interest in him and invested in his future.

Soon after returning to Hawaii, Laureta hooked up with two other young lawyers, Bert Kobayashi and Russell Kono, joint partners in a law firm they had recently started. Laureta said they wanted him to join their practice and offered to pay him a meager salary while he studied for the bar.

“How much do you think you need to live on?” they asked him. “Can you accept a hundred dollars a month?”

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, $100 in 1953 was equivalent to less than $1,000 today, hardly enough to support a family, and the Lauretas’ first child was on the way. It would be the first of many times over the next six decades that Evelyn would be a pillar of strength for the family.

“She subsidized my education to pass the bar,” Laureta said, describing how his wife supported him financially, working long hours as a nurse while he studied. Within months, Laureta became just the third Filipino in the history of Hawaii to pass the bar exam.

In 1959, Hawaii became a state. Daniel Inouye was elected as its first member of the U.S. House of Representatives and picked Laureta as his administrative assistant. After a few years in Washington, D.C., Inouye was elected senator, and Laureta became the first Filipino to ever serve in a governor’s cabinet.

In 1963, Hawaii Gov. John Burns made Laureta director of the state Department of Labor, a post he held for four years, until he was appointed First Circuit Court judge, the first Filipino-American judge in history.

Laureta moved to Kauai in 1969, and he presided over cases in Fifth Circuit Court for the better part of the decade, before breaking racial and ethnic barriers once again. In June 1978, Laureta was confirmed as the first federal judge of Filipino ancestry in U.S. history.

On the back wall of Laureta’s shed hangs a letter signed by President Jimmy Carter, nominating him judge for U.S. District Court for the Northern Mariana Islands, a territory established by an Act of Congress just a year before. It was a brand new position in the federal government, and Laureta had been appointed to hold court in Saipan, an island in the western Pacific less than a tenth the size of Kauai.

“There’s no federal court building in Saipan,” said a May 1978 Honolulu Advertiser article about Laureta’s appointment. “Court will initially be held in the lounge of the Saipan Continental Hotel, at one time a small gambling casino when slot machines were legal on the islands.”

Laureta told the Advertiser’s reporter that he and his family planned to stay in the hotel until they find a house.

Forty years later, Laureta relishes the near-century of memories he holds. His granddaughter said he recently began insisting his family help him set up a place to display his archives.

Laureta’s shed has become a miniature museum of his life. There is no room left on its walls, and giant bins underneath the table are packed with old photo albums, documents, newspaper clippings, awards and certificates.

It has been a long and varied life, but Laureta said that more than anything else, he wants to pass on the lessons he learned about the strength of a community that gave him everything and provided him with the opportunity to rise from a plantation camp to some of the highest courtrooms and public offices in the world.

“I would like the people to realize that there are things in our community that we can do by ourselves to make the world a better place to live in,” he said. “Without the strength I had from them, I don’t think I could have accomplished anything.”

•••

Caleb Loehrer, staff writer, can be reached at 245-0441 or cloehrer@thegardenisland.com.

Outstanding article. Make me proud of what he has accomplished and for who he is.

Great article on Uncle Alfred who is my grandmother Maggie’s older brother. Such an incredible journey for him!

What a wonderful, inspirational story. Thank you Caleb Loehrer for researching and writing it, and thank you editor Bill Buley for assigning Mr. Loehrer to this project and for publishing it. Hawaii has always been a place where immigrant families could work their way up from nothing. That tradition started with Polynesian settlers arriving on voyaging canoes; then British explorers and sailors like the historically important John Young; then American missionaries and their children like President Sanford Dole; then Japanese and Chinese plantation laborers and merchants; then Filipino laborers, doctors, and nurses; and so many more ethnicities from many places. After visiting Hawaii 3 times on summer vacations in the 1980s I knew Hawaii should be my home and moved here permanently in 1992. Such a beautiful rainbow of races, cultures, and languages. Nunui ko’u aloha i na po’e a pau, noho ana ma ku’u kulaiwi hanai. We are all equal in the eyes of God, and we should all be treated equally under the law by our government so our talents can blossom and thrive.

What an amazing journey. As part Filipino, I am immensely proud of his accomplishments. What a great role model and truly inspirational to many. Thank you for featuring “The Judge”.