NEW YORK — The Miami Herald’s stories on sex trafficking charges against billionaire financier Jeffrey Epstein illustrate a counter-intuitive trend: Investigative journalism is thriving as the news media industry struggles.

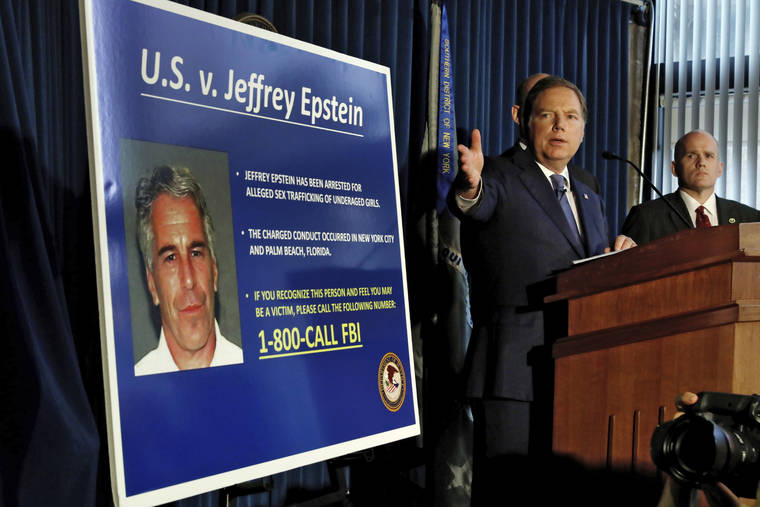

In announcing new charges against Epstein 11 years after the financier secretly got a sweetheart deal from federal prosecutors in Florida to settle nearly identical allegations, New York prosecutor Geoffrey Berman said Monday that his team was “assisted by excellent investigative journalism.”

“It’s really gratifying,” Aminda Marques Gonzalez, president, publisher and executive editor of the Herald, said Tuesday. “You hope your work will have impact. It’s beyond your expectation to have your work cited as the basis for an arrest.”

While Berman did not cite the Herald by name, it was obvious he was referring to the work of reporter Julie K. Brown, who in a series of stories, including a big investigative piece last November, reported on at least 60 women who said they had been sexually abused by Epstein between 2001 and 2005, when they were minors. Eight agreed to be interviewed.

The Herald’s story came as news organizations are finding that investigative work helps them stand out and is rewarding in a rough business climate. Recent examples include stories looking into Russia’s involvement in the 2016 election, Donald Trump’s behavior before and during his presidency and sexual misconduct by public figures.

“It used to be said in this business that we couldn’t afford to do investigative journalism,” said Martin Baron, executive editor of the Washington Post. “Now we have to do investigative journalism. First of all, it’s at the core of what readers expect of us and increasingly, it’s at the core of our business model as well.”

Three weeks ago, the Post announced it was adding 10 new positions devoted to investigative journalism — increasing its staffing in this area from eight to 26 since the beginning of 2017.

The newspaper won a Pulitzer in 2018 for its revelations about sexual misconduct by Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore. The Moore story was part of the Post’s “rapid-response” team; along with the traditional long-term projects, news organizations are seeking more nimble investigative teams that respond to breaking news.

Besides adding staff, Gonzalez said she has tried to establish a culture at the Herald where departments throughout the newsroom are pursuing enterprise projects. What she doesn’t want is an investigative team “isolated in a corner of the room, which used to be the case.”

The New York Times also has emphasized an investigative ethos across the newsroom. The Times won a 2019 Pulitzer for an exhaustive study of Trump family finances and, in 2018, shared a Pulitzer with The New Yorker for reporting on sexual misconduct.

“Broadly speaking, with the attacks on the press and on facts there has been a reinvigoration of the investigative mission of journalism,” said Matthew Purdy, deputy managing editor who oversees investigations at The New York Times. “I don’t mean just at the Times but across the industry. It’s sort of unmistakable.”

Big investigations aren’t new. There’s a history of memorable digging on Watergate and the Pentagon Papers. And Baron was editor at the Boston Globe when it published a series of stories revealing priests’ history of sexual abuse and the church’s ensuing cover-up, which was chronicled in the 2015 movie “Spotlight.”

But when the newspaper industry’s financial downturn intensified in the 2000s, investigative units were often cut. Many of the news organization’s bean counters saw them as luxuries, said Doug Haddix, executive director of the organization Investigative Reporters & Editors.

IRE’s membership is now at a record-setting 6,178, up from around 4,000 in 2010, Haddix said. Its Houston conference last month set an attendance record. Where the typical IRE conference attendee once worked at a newspaper, now a member is just as likely to work in television or at a non-profit web site. Sold-out IRE workshops show reporters and editors are looking to become more employable by learning digital journalism and how to better mine public records, he said.

Things were looking so dire a decade ago that Michael Hudson thought he’d be using his skills in a different profession by now, perhaps as a private investigator. Instead, he’s global investigations editor at The Associated Press, which has beefed up investigation teams internationally and domestically. The AP also is creating a dedicated team focused on investigations that spin off breaking news.

The AP won a 2019 Pulitzer for investigations around the conflict in Yemen, and in 2016 an all-female team of investigative reporters won a Pulitzer for breaking news about slavery in the fishing industry in Southeast Asia.

“I feel like there’s been a really heartening turnaround,” Hudson said.

While the mission is important, news organizations say the work helps the bottom line. The AP found its Yemen stories were very popular with readers. Many of the Post’s new subscribers cite investigative work as a reason for signing up, and those are the stories readers are drawn to, Baron said.

In the body of the digital version of Brown’s project last November, the Herald invited readers to click if they wanted a subscription. The newspaper collected as many new subscribers in a couple of days that it normally gets in a couple of weeks, and Gonzalez was stunned to find that roughly three-quarters of them lived outside of the Miami area.

They were subscribing to support the journalism.

There seems to be a new spirit among journalists who are more willing to elevate the good work of colleagues at other organizations, as this week has proven with the Herald, said Kyle Pope, editor of the Columbia Journalism Review.

“We as an industry need to stand together,” the Post’s Baron said. “While we’re competitors, we also need to be mutually supportive of quality work. If it’s a trend, it’s a good trend.”