BEDFORD, Va. — Marguerite Cottrell remembers the summer day 75 years ago when a Western Union telegram was delivered to her family farm as her mother was hanging clothes on the line to dry.

Her mother read it, sat down and wept.

Cottrell’s older brother, John Reynolds, had been killed in the D-Day invasion of Normandy on the coast of France.

“I knew something bad had happened,” said Cottrell, who was 4. She remembers her mother telling her: “Well, little Jack has gone to heaven. I don’t know what we’re going to do.”

All over the little town of Bedford, Virginia, nestled next to the Blue Ridge Mountains, similar telegrams were delivered that summer — nine of them on one day — with the same opening line expressing the secretary of war’s “deep regret” that a loved one was killed or missing.

Twenty men from Bedford or the surrounding area were killed on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Nineteen fell while trying to take Omaha Beach as members of Company A of the 116th Infantry Regiment. The 20th man was in a different company.

The decisive World War II invasion took a horrific toll on Bedford, a town of about 4,000 at the time. Its D-Day losses were among the steepest, proportionally, of any community in America.

The dead were country boys who came of age during the Depression and joined the National Guard before the war for extra income and uniforms that local girls thought looked sharp, according to author Alex Kershaw’s 2003 best-seller “The Bedford Boys.”

Frank Draper and Elmere Wright were local baseball standouts. Wallace Carter worked at the town’s pool hall. Earl Parker left behind a young bride and a daughter he never got to meet. Twins Ray and Roy Stevens hoped to run a farm after the war, but only Roy survived.

Their time in combat was short. Among the first waves in the assault on Omaha Beach, Bedford’s soldiers were wiped out by Nazi machine guns and mortars within minutes after their landing craft hit the sand.

“They were waiting for us, the minute the ramp went down, they opened up,” said Elisha Ray Nance, one of the few Bedford Boys who survived that deadly beach landing, in comments recorded in “Bedford Goes to War,” a book by local historian James Morrison.

In 1996, Congress designated a plot of land next to Bedford as the site of the National D-Day Memorial, a monument to the more than 4,000 Allied troops who lost their lives in the battle.

“When people come here, it is important to see the town as the monument itself,” President George W. Bush said at a 2001 ceremony dedicating the memorial. “This is the place they left behind.”

Amateur historian Ken Parker and his wife, Linda, have turned the town’s old pharmacy into a coffee shop and tribute center to the Bedford Boys. Green’s Drug Store was where Bedford Boys had hung out as high schoolers and their wives and girlfriends exchanged gossip and news during the war.

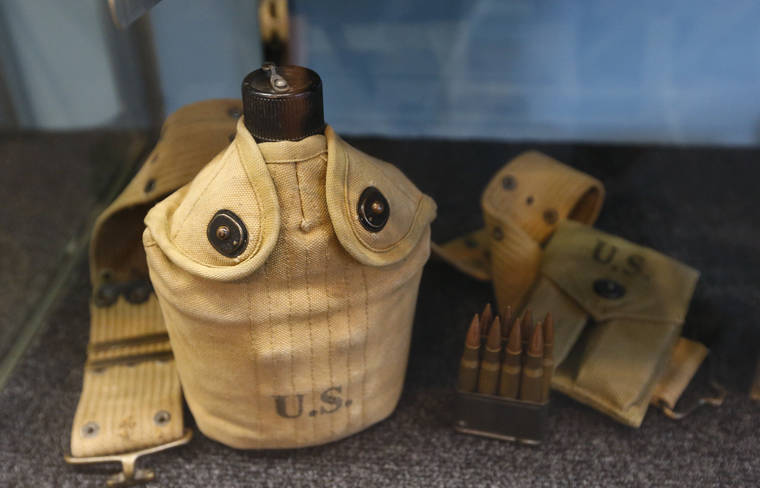

The center is now filled with war-era uniforms, pictures and other items, including the teletype machine that Parker says printed out the notices when the boys were killed.

On a recent Monday, Bedford resident Maryellen Cunningham came in to take a look around. She said seeing the old teletype gave her chills.

“I can’t even imagine the operator that was getting one telegram after another after another,” she said.

The Parkers — who recently moved to Bedford from Oklahoma — said they get similar visits all the time from Bedford residents, who often want to place a war-related family heirloom on display at the new tribute center.

Nance, the last surviving Bedford Boy, died in 2009. Only a few of the fallen soldiers’ siblings are still alive. But the Parkers said younger generations have held on to many of the boys’ letters and other keepsakes, handing them down through generations almost like sacred relics.

The couple said one of the Bedford Boys’ nephews recently found a stash of unopened letters his grandmother had sent to her son before she knew he had been killed on D-Day.

“They just bottled this up for so long,” Linda Parker said. “They can finally open that box and let the stuff out.”

Cottrell, who recently dropped in at Green’s Drug Store, said her mother used to open up an old trunk with her brother’s belongings on Sunday afternoons and read his letters. Cottrell said her mother blamed herself for letting Jack enlist and talked about him often to keep his memory alive.

“There’s so many people that have passed away, you know, that this would have meant so much to,” she said of the drugstore. “My mom would have loved coming here.”