How safe is running a marathon? Heart doctors say it depends

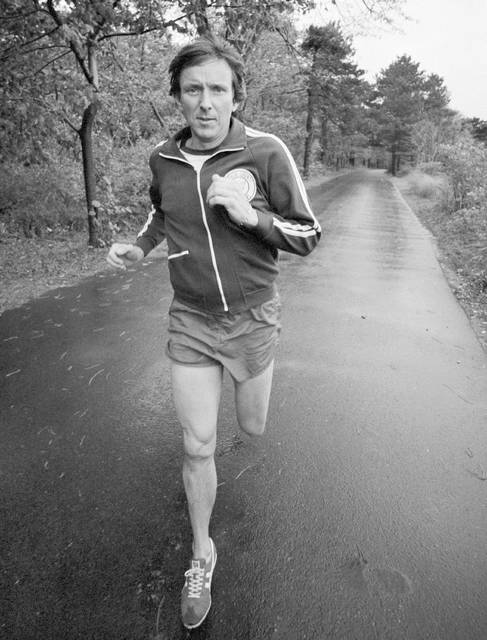

In this November 1977 file photo, marathoner Jim Fixx runs on a road near his home in Connecticut. In July 1984, the acclaimed author and running guru died of a massive heart attack while trotting along a country road in Vermont. Boston Marathon race director Dave McGillivray is cautioning people thinking of running a marathon to talk with their doctors before hitting the road, especially if they have coronary artery disease or a family history of it. (AP Photo/Jerry Mosey, File)

In this Sept. 5, 2018, photo provided by Katie McGillivray, Boston Marathon race director Dave McGillivray gives the thumbs-up after undergoing an angiogram at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. McGillivray, recovering from subsequent open-heart triple bypass surgery, is cautioning people thinking of running a marathon to talk with their doctors before hitting the road, especially if they have coronary artery disease or a family history of it. (Katie McGillivray via AP)

This Nov. 1, 1977 file photo shows marathoner Jim Fixx near his Connecticut home where he runs just for the fun of it. In July 1984, the acclaimed author and running guru died of a massive heart attack while trotting along a country road in Vermont. Boston Marathon race director Dave McGillivray is cautioning people thinking of running a marathon to talk with their doctors before hitting the road, especially if they have coronary artery disease or a family history of it. (AP Photo/Jerry Mosey, File)

In this Oct. 14, 2018, photo provided by Katie McGillivray, Boston Marathon race director Dave McGillivray uses a walker after undergoing open-heart triple bypass surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. McGillivray, a lifelong competitor, is cautioning people thinking of running a marathon to talk with their doctors before hitting the road, especially if they have coronary artery disease or a family history of it. (Katie McGillivray via AP)

In this Aug. 23, 2018 file photo, Dave McGillivray, race director of the Boston Marathon, runs past fans inside Fenway Park, as he commemorates the last leg of his 80-day run in 1978 to benefit the Jimmy Fund, before a baseball game in Boston. A few months later, McGillivray underwent triple bypass surgery after suffering chest discomfort and difficulty breathing while running. He is cautioning people thinking of running a marathon to talk with their doctors before hitting the road, especially if they have coronary artery disease or a family history of it. (AP Photo/Elise Amendola, File)

BOSTON It was the death heard round the running world.

BOSTON — It was the death heard ‘round the running world.

In July 1984, acclaimed author and running guru Jim Fixx died of a heart attack while trotting along a country road in Vermont. Overnight, a nascent global movement of asphalt athletes got a gut check: Just because you run marathons doesn’t mean you’re safe from heart problems.

Fast-forward 35 years, and Boston Marathon race director Dave McGillivray is amplifying that message for marathoners, especially those who have coronary artery disease or a family history of it.

“Being fit and being healthy aren’t the same things,” McGillivray says.

He should know. Six months ago, the lifelong competitor underwent open-heart triple bypass surgery after suffering chest pain and shortness of breath while running.

As marathons, ultramarathons, megamile trail races and swim-bike-run triathlons continue to explode in popularity, doctors are re-prescribing some longstanding advice: Get a checkup first and talk with your primary care physician or cardiologist about the risks and benefits before hitting the road.

For McGillivray, 64, the writing was on his artery walls. Both of his grandfathers died of heart attacks; his father had multiple bypasses; his siblings have had heart surgery; and a brother recently suffered a stroke.

Neither McGillivray’s marathon personal best of 2 hours, 29 minutes, 58 seconds, nor his decades of involvement in the sport could protect him.

“I honestly thought that through exercise, cholesterol-lowering medicine, good sleep and the right diet, I’d be fine,” he says. “But you can’t run away from your genetics.”

Aerobic exercise such as running, brisk walking, cycling and swimming is known to reduce the risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke and certain types of cancer, and it’s been a key way to fight obesity, Type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis and more. Studies have shown those who exercise regularly are more likely to survive a heart attack and recover more quickly than couch potatoes.

But new research is providing a more nuanced look at “extreme exercise” and the pros and cons of running long.

In a study published in December in Circulation, the journal of the American Heart Association, researchers in Spain found signs suggesting that full marathons like Boston may strain the heart. They measured substances that can signal stress and found higher levels in runners who covered the classic 26.2-mile (42.2-kilometer) marathon distance compared with those who raced shorter distances such as a half-marathon or 10K.

Only about one in 50,000 marathoners suffers cardiac arrest, the researchers said, but a high proportion of all exercise-induced cardiac events occur during marathons — especially in men ages 35 and older. The Boston Marathon and other major races place defibrillators along the course.

“We typically assume that marathon runners are healthy individuals, without risk factors that might predispose them to a cardiac event during or after a race,” writes Dr. Juan Del Coso, the study’s lead investigator, who runs the exercise physiology lab at Madrid’s Camilo José Cela University. Running shorter distances, he says, might reduce the strain, especially in runners who haven’t trained appropriately.

Dr. Kevin Harris, a cardiologist at the Minneapolis Heart Institute at Abbott Northwestern Hospital, says he had a patient preparing for the Twin Cities Marathon who struggled to exceed 10 miles (16 kilometers) in training. The man’s family doctor insisted he get a stress test, and he wound up needing double bypass surgery to detour around dangerous blockages in his arteries.

“Running is good, and we want people to be active. But your running doesn’t make you invincible,” Harris says. “The bottom line is that individuals with a family history — especially men who are older than 40 and those people who have symptoms they’re concerned about — should have an informed decision with their health care provider before they run a marathon.”

That family history is crucial.

Fixx, whose 1977 best-seller “The Complete Book of Running” helped ignite America’s running boom, was 52 when he collapsed and died. An autopsy showed he had blockages in two of his heart arteries. He had a mix of risk factors. His father died at 43 of a heart attack, and although Fixx quit smoking, changed his eating habits and dropped 60 pounds, it turned out he couldn’t outrun those risks.

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s late husband, tech entrepreneur Dave Goldberg, was 47 when he died while the couple was vacationing in Mexico in 2015. Goldberg had been running on a treadmill when he fell, and an autopsy revealed he had undiagnosed heart disease.

Former U.S. House Speaker Paul Ryan, who is 49, has said his own strong family history of heart disease is what motivates him to work out regularly and watch his diet. His father, grandfather and great-grandfather all died of heart attacks in their 50s.

“If you’re going to take on strenuous exercise later in life, and especially if you have active heart disease, it’s clearly in your interest to be tested and make sure you can handle it,” says Dr. William Roberts, a fellow and past president of the American College of Sports Medicine.

McGillivray says his doctor has cleared him for Monday’s 123rd running of the Boston Marathon, which he’ll run at night after the iconic race he supervises is in the books. It will be his 47th consecutive Boston, and this time, he’s trying to raise $100,000 for a foundation established in memory of a little boy who died of cardiomyopathy — an enlarging and thickening of the heart muscle.

“Heartbreak Hill will have special meaning this year,” McGillivray says.

“My new mission is to create awareness: If you feel something, do something,” he says. “You have to act. You might not get a second chance.”

———

Follow Bill Kole on Twitter at https://twitter.com/billkole .