In September 1976, J Robertson found himself the captain aboard a 36-foot sailboat with a busted mainsail docked in a harbor in Honolulu. With nothing to do and nowhere to in particular to go, he made a life-altering decision.

“I got all kinds of friends on Kauai,” he thought to himself. “Why don’t I sail over there? I got a boat with six months worth of food on it. I’m only a hundred miles away.”

“So I fix the boat, got everything back into working order, and got a crew. I sailed to Kauai, pulled into Nawiliwili and never left.”

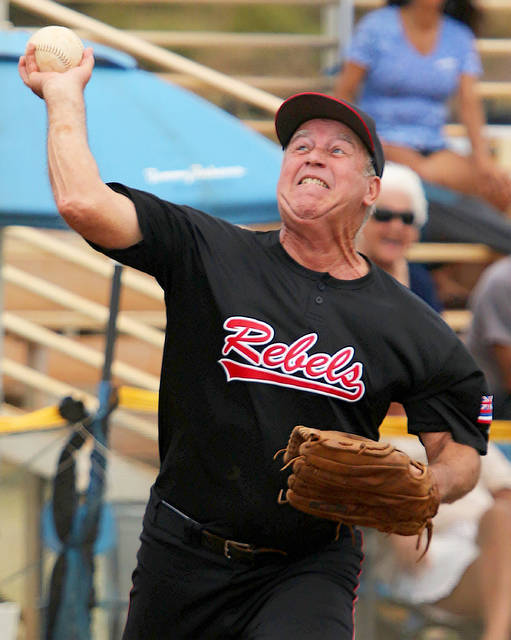

Robertson explained how he ended up on the island in an interview this week that started in his office at the Hoike Community Television studio in Lihue and ended on a nearby baseball diamond. The following is story is built around excerpted transcripts of that interview.

(Italic text indicates editorial notes added afterward for context.)

The beginning

Robertson: My first name is J. There’s no “AY.” That’s my full legal and complete name.

I’m actually the third. My grandfather was born in the south at the turn of a different century. And back in those days in the South it was somewhat customary to just give an initial.

J’s grandfather moved to Kansas and started a grocery store in the early 1900s and then immigrated to California during the Great Depression, eventually settling in Los Angeles, where J grew up. J was born in 1951. After high school, he attended California State University, Northridge where he played baseball.

JR: We were national champions in Division 2 my freshmen year. And we finished second my junior year, and unfortunately Cal State Irvine knocked us out my senior year. We didn’t get to go to the World Series. That was no fun.

What pitches did you have?

All of ‘em. Forkball, curve, slider, fastball. That’s not gonna be in the story is it?

Why wouldn’t you want that in?

I don’t make very much noise about any of that around here. It’s not Kauai style.

What was your strikeout pitch?

It would depend on the hitter, but more often than not it would be the forkball — untouchable.

You throw it exactly like a fastball, and what happens is, it just slips out of your fingers, takes about one-and-a-half rotations to the plate, and then just collapses. So they’re looking at it — it looks like a knuckleball, but it drops like a curve.

But if you hang it?

Oh, it goes very far. But most of the time you don’t cause those pitches are very low. They think it’s a fastball coming at ‘em till it’s too late. That was a devastating pitch. But actually when I got older, my fastball got a lot better ‘cause I was playing in South America.

Baseball in Ecuador — “El Verdugo de Barcelona”

The story of how J ended up in South America begins with a fan. One day during practice, a Latino man showed up, asked the coach if he could try out, and promptly displayed a level of skill that was not commensurate with collegiate baseball in America. The man was undeterred.

JR: The guy was so gung-ho dedicated that he asked if he could be a fan. And of course the coach was like, “of course you can.” The guy was nuts! He had a cowbell. We gave him a broken bat and a trashcan. He would sit right on the edge of the visiting team’s dugout. And the whole game he would be ringing his bell and beating the holy hell out of that trash can — we had to buy him a whole bunch of extra trash cans.

It was hilarious. He was so irritating and so annoying. One time we were playing Gonzaga in the regional tournament on our field. So Jose was going crazy, and he was giving the first baseman a whole bunch of grief about something — he had made an error. So he was really riding him. And the first baseman snapped in the middle of the game, ran over, leaped over the fence, went into the stands after the guy. He was just nuts. And we’re all just rolling on the other side of the field.

Jose turned out to have some connections with professional baseball in Ecuador.

JR: One of his best friends was a coach of a team in Ecuador — The National Federation of Sports of Ecuador. And they were perennially second and third place out of a five-team league and never could beat Barcelona. And Barcelona was the Yankees, so they dominated everything.

The team, Emelec, which was owned by Empresa Eléctrica, their power company had always hired Dominicans and Puerto Ricans and Cubans, and every year they would have a hard time with these guys because — especially the Cubans and the Dominicans — they would come down and just be drunk and stoned out of their minds, and they’d go crazy and lose it.

So they finally decided to pitch in some extra money — “Let’s hire some gringos.” And they contacted Jose, our fan, and so he came to the team and asked three Latin guys and me — I was the only white boy — the four of us, if we could go down.

So you took it without hesitation or what?

No. I was like, “you gotta be nuts. Why would I do that? That’s crazy! Why am I going to Ecuador?”

How did they convince you?

They didn’t. I went home, went to bed, woke up at about 3:30 in the morning and went “$#%!. I wonder if I can call him now and tell him I wanna go. Yeah I think I wanna go! This sounds like fun!”

And they expedited me a passport, got me a ticket, and I mean, like within 10 days I think we were flying down into Ecuador.

A brief article in the Thursday, Aug. 8, 1974 issue of The Los Angeles Valley News says, “Four members of last season’s baseball team at California State University, Northridge are spending their summer playing baseball in Guayaquil, Ecuador.”

The newspaper spelled J’s first name, incorrectly — “Jay” — but says that he and three other players from the CSUN team “were invited by officials in the Ecuador government after recommendation by Jose D. Freire, III, a scout and sports writer.”

How much did they pay you?

Really, a lot of money for there, but actually nothing by American standards. Our housing was paid for. All the food was paid for. All the transportation was paid for. We got probably $400 a month cash to spend, which is one of their top civil servant’s salaries.

It was ridiculous, honestly. We’re making as much money as these guys who are working their ass off all day! This is stupid! It wasn’t any real money to speak of, but based on their economy, I mean, we had millions. We had maids. We had people take care of everything. We had cooks. It was like, unreal.

Guayaquil, Ecuador — it was an amazing place.

It was 1974. We ended up winning the championship. I beat Barcelona in every game and became “El Verdugo de Barcelona.”

What does Verdugo mean?

Um, slave owner — slave master.

And that was the champion team?

Oh yeah. Nobody could beat them, and I caused them all kinds of grief. I would set a strikeout record almost every game the first year.

J played 40 or 50 games over the summer months, returning to California in the off-season, where he earned a living as an apartment manager at a complex that billed itself as “contemporary adult living.” For J, then a single man in his early-twenties, it was a paradise. Life was good, but a phone call from his father changed his life.

A sailboat, a squall, an island

JR: What had happened was, my dad was an L.A. County fireman. And when he retired, he had a sailboat. He always loved sailboats and stuff like that, so he had a sailboat from when I was like 10 years old.

We’d go out. We sailed. He was so dogmatic and dictatorial about it. We had to stay on course. I’m like, “I wanna just go,” and he’s like, “no, you’re staying on course.” Ah, it drove me nuts, but I learned how to navigate.

When I go to South America, his lifelong dream and ambition was to sail to Hawaii. So he got a bunch of his fire buddies together. They all packed up the boat, and off they sailed. And they sailed over to Hilo, went around to Kona, then off to Molokai and stayed there. Went to Lahaina — stayed there. Then he made his way to Honolulu.

At that point, J’s father, who stands six feet, five-inches tall, grew weary of the boat cabin’s low ceiling and cramped quarters. Dreading the prospect of sailing the small vessel back to California across thousands of miles of open sea, J’s father called on his most-trusted navigator to make the trip for him. It was 1976.

JR: So I had just gotten home. It was September, I had just gotten home from Ecuador, and he called and says, “Hey. I need help getting the boat back. Can you come and help me?” And I’m like, I really don’t wanna go. First of all, I don’t like Hawaii. They’ve got beautiful beaches and they just bastardize the whole place. They build nothing but hotels on their best lands, and I don’t need any part of that.

His father persisted, and eventually J agreed to fly to Honolulu and sail the boat home. Three days into the trip, J and his ship ran into trouble. He and another crew member had finished their watch and went below to sleep, leaving two other men in the cockpit to keep a lookout.

JR: I’ve just fallen asleep, and all of a sudden I hear this BOOM! I’m like, “what the hell?” I go running up out into the cockpit, the two monkeys are in their sleeping bags (he made a snoring sound) sleeping on watch!

They weren’t paying attention. We could have been heading to China. They sailed into a squall. It blew out the rigging at the top of the mast. The sail is in the water, under the boat.

It was very windy. It was a full squall, so there was all hell breaking loose. We get everything pulled up, and I’m just like, aw you’re kidding me. So we turn around, limp back to Honolulu.

You had a little diesel engine?

Regular gas engine. So we’re using both that and sailing with the mainsail. Almost ran out of gas coming around the Diamond Had, trying to get into the Ala Wai. I’m like, “God, please, please.”

J sat around the harbor trying to figure out what to do with himself and his busted boat, when he realized something.

JR: When I was in college, Continental Airlines had a $79 air fare to Kauai, but you had to be a college student to get the ticket. So every week I would go, and I would buy a ticket, take my friend to the gate, shake their hand and off they go. Next week, buy a ticket, and off they go. So I had all kinds of friends over here.

So they were living here, and I was like, “I got all kinds of friends on Kauai. Why don’t I sail over there? I got a boat with six months worth of food on it. I’m only a hundred miles away.” So I fix the boat, got everything back into working order, and got a crew, sailed to Kauai, pulled into Nawiliwili and never left.

I was like, “damn. This is home.”

Robertson is managing director of Hoike Kauai Community Television, a public education and government access organization that offers training, equipment and a channel for locally produced programming.

•••

Caleb Loehrer, staff writer, can be reached at 245-0441 or cloehrer@thegardenisland.com.

Fastball…i don’t know. Sports only heh. Not politics.