Capturing a culture

Photo courtesy Daniel Finchum

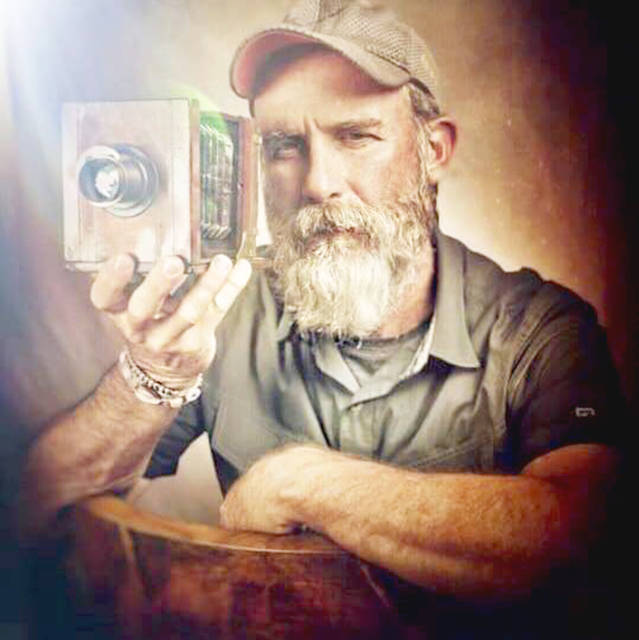

Kauai photographer Daniel Finchum poses with one of his circa-1850s cameras.

Photo courtesy Daniel Finchum

Photo by Daniel Finchum

“Cook’s Landing” shows two young Hawaiians pulling a rope attached to the Captain James Cook statue in Waimea, in Hofgaard Park, as if trying to bring it down.

Photo by Daniel Finchum

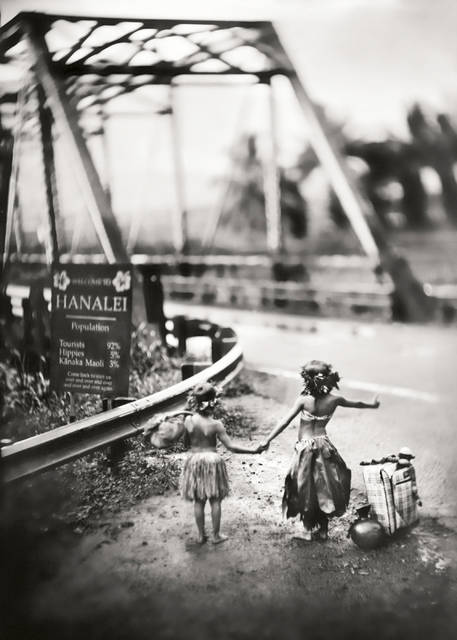

“Bridge to Gentrification” shows local keiki getting out of Hanalei at the river bridge. ON THE COVER: In “Bliztkrieg Baby (Aloha Ammo),” a Kanaka Ma‘oli keiki offers a lei to a menacing tank.

Photo by Daniel Finchum

The title of Daniel Finchums photo essay, Bruises in the Garden, lets you know right away these are not going to be feel-good pictures of sunsets, waves and beaches.

The title of Daniel Finchum’s photo essay, “Bruises in the Garden,” lets you know right away these are not going to be feel-good pictures of sunsets, waves and beaches.

As Finchum says of his work: “I take jabs in this series. I really do take jabs, but I do it in a lighthearted way. I’m just trying to get people to think about what happened and what we can do to fix this.”

The Kapaa man’s wet plate photographic series deals with “past and present transgressions against the Hawaii people and the ‘aina (land). The offenses have impacted the psyche of the Kanaka Ma‘oli. Some Kanaka are aggressively vocal about the issues and others are more subdued. Yet all Hawaiians deeply connected to their history and land support to varying degrees the Kanaka’s expression of certain claims.”

He stages the scenes in his photos carefully, deliberately, to send messages, to get people to think about what has happened in Hawaii.

One of his photos, “Cook’s Landing,” shows two young Hawaiians pulling a rope attached to the Captain James Cook statue in Waimea, as if trying to bring it down.

Another, “Royal Flush,” shows a Hawaiian woman, her hand to her face, sitting on a toilet outside, the ocean and mountains in the background.

“Bridge to Gentrification” depicts two keiki standing near the Hanalei Bridge, luggage at their side, thumb out, hitchhiking, indicating they are leaving. A sign says, “Hanalei Population: Tourists 92 percent, Hippies 5 percent, Kanaka Maoli 3 percent.”

And one of Finchum’s favorites, “Blitzkrieg Baby (Aloha Ammo),” shows a young Hawaiian girl holding a lei up to a tank.

“I approach these issues satirically to reach the recesses of the Hawaiian consciousness,” he wrote.

Finchum, who has lived on Kauai nearly 40 years, said “I have felt the pains of growth and change. I can only imagine how the Kanaka feel. This is for them, to speak their message.”

He said he is not a scholar on Hawaiian history and culture, but he believes he does understand what they have gone through.

“I feel their pain,” said Finchum, who is part Native American.

Finchum’s exhibit opening for this series will be held 6 to 8 p.m. Saturday at Ha Coffee Bar on Rice Street in Lihue. He invites the public to “Come and soak in this important, thought-provoking work.”

He will be there to give a brief statement, then answer questions about his work, which will continue on display there indefinitely.

He said visitors can anticipate “a unique experience” of his solo exhibit of wet plate collodion images, a process that was developed in 1851. The award-winning photographer worked on this newest series for the past two years.

Inspired by the work of British street artist Banksy, Finchum photographs carefully choreographed scenes using 1850s processes and equipment.

Through provocative imagery, some deeply personal, Daniel attempts to evoke a pause, serious consideration, and respectful discourse between residents and visitors,” according to Finchum’s press release.

And it’s not about money.

Finchum said his photo essay has the blessings of kumu and local practitioners, and he has gained many friends in the process of putting it together.

“This series is not meant to sell,” he said, adding it is meant to get people to reflect, to think, to question. “I just want it to be viewed by as many people as possible.”

Finchum, who is retired from government work, enjoyed some success as a photographer in his early 20s, but then, “life got in the way” and he gave it up.

He began doing wet plate photography — only about 2,000 do it worldwide — about four years ago. And it was then his “pent up creativity” overflowed.

“It was very therapeutic for me,”he said.

Today, photography and traveling are his passions.

“I don’t consider it work,” he said.

In a world dominated by the instant results of digital photography, the wet-plate process is painstaking and detailed. It means he has to “bring a portable darkroom in the field with me wherever I go and do all the developing wherever I go.”

He mixes his own chemistry from 1850s recipes and also uses vintage lenses from Europe that date back to the middle of the 19th century. Each image is handcrafted and carefully staged.

“It is his desire to capture the culture of Kauai’s Kama‘aina, or people of the land, through the eyes of its residents regardless of race, religion, gender, age or length of residency. He views his work as collaboration with them,” the release states.

His first photo essay book is “Kama‘aina Soul — Anthology: The Wet Plate Photography of Daniel Finchum.”

This second essay book reflects some images that are open to interpretation. Others leave no doubt about what he wants it to say.

“All should lead to greater understanding about the Hawaiian past and current grievances that are implicit in its voice today. My intention is to entertain and throw a sucker punch simultaneously,” he wrote in “Bruises in the Garden.”

He said he feels the pulse of Hawaiians.

“My artistic concern is to show their heartbeat implicitly expressed through my camera. What hides behind the facade of a smile, the offering of a lei, the performance of a dance, a greeting, luau, a kiss for which Hawaii is so graciously known? Is ‘Aloha’ sacrificed on the altar of conciliation?”

He talks about hula dancers doing something sacred to Hawaiians, going through the motions night after night, for the entertainment of visitors, and reflects that in his photo, “Wound Up,” that shows a hula dancer and drummer, wind-up keys in their backs, a cruise ship in the background.

He was worried no one would want to host the photo essay because its content might be “too thought-provoking,” but Ha Coffee Bar welcomed it.

“I think people are tired of seeing rainbows and turtles pictures. I think people are ready for this line of work,” he said.

•••

Bill Buley, editor-in-chief, can be reached at 245-0457 or bbuley@thegardenisland.com.