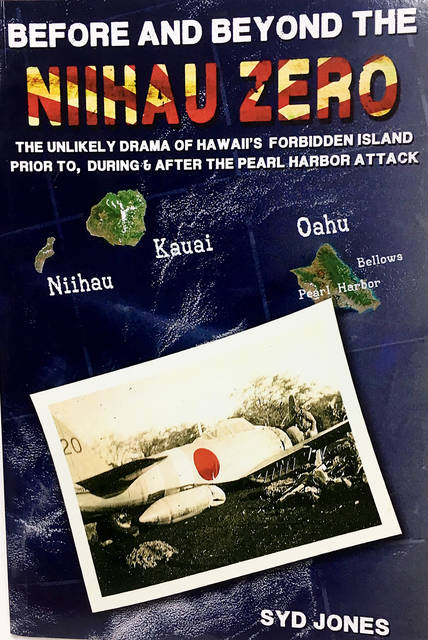

About a year or so after I started working at The Garden Island nearly six years ago, Keith Robinson of the Robinson family on Ni‘ihau stopped by our office with a book he wanted me to read. It was titled, “Before and Beyond the Ni‘ihau Zero: The Unlikely Drama of Hawaii’s Forbidden Island Prior To, During and After the Pearl Harbor Attack,” and was written by Syd Jones.

Jones was given rare access to Ni‘ihau and allowed to interview its owners and those who lived there. The result of this book, published in 2014, is a detailed account of what happened when a Japanese Zero damaged in the Dec. 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor came to land on this privately owned island, a place where residents were not aware of the raid at Pearl.

As the back cover tells us, “The Zero pilot survived for almost a week on what locals call the ‘Forbidden Island,’ assisted by a local worker, while terrorizing the island’s population before being killed by a native Hawaiian.”

Such is usually the stuff of movies. But this was real life. It happened.

Daniel A. Martinez, Pacific War historian, wrote, “The incident at Ni‘ihau will probably not be remembered as it was during the war. Folklore and legends were part of the local memory. The saying in the islands that “you have to shoot a Hawaiian three times before he is mad” stems from the shooting of Ben Kanahele by the pilot Nishikaichi. In 1943, a popular song blared on the radio from New York to Honolulu. Titled “They Couldn’t Take Ni‘ihau No-how,” told of the herosim of the Hawaiian Ben Kanahele. Perhaps that is part of the story that is often eclipsed in other author’s renditions.”

This book contains numerous photos, reports and documents that provide an inside look at what happened, the people involved and how it affected their lives.

The wreckage of the plane was not forgotten. It later became part of an aviation museum in Hawaii.

“The Zero display brought to the forefront what happened the day of the attack, the conflict that ensued on the island in the days that followed, while unexpectedly generating a modern controversy in the process,” according to the back cover summary.

If you really want to know more about the fascinating story of the Zero that crashed on Ni‘ihau on Dec. 7, 1941, then read this book. It asks and answers many questions. It is history, and written as such. But one paragraph puts well what was at stake for the Zero pilot, Naval Airman First Class Shigenori Nishikaichi:

“Nishikaichi was in a tough spot. He was being held on an enemy island, with a growing likelihood of being given over to U.S. military officials. His weapon, the papers and map he had used during the attack had already been taken away; his only path to possible escape was the radio in his plane to make contact with the submarine — if it was still nearby. At the same time, he needed to destroy the valuable Zero and its secrets before the enemy got their hands on it. Somehow, he would have to find a way…”

This happened on an island you can see from Kauai.

Keith Robinson, by the way, is mentioned several times in the book, and I thank him for bringing this to my attention.

•••

Bill Buley, editor-in-chief, can be reached at 245-0457 or bbuley@thegardenisland.com.