VATICAN CITY — The founder and all-female editorial board of the Vatican’s women’s magazine have quit after what they say was a Vatican campaign to discredit them and put them “under the direct control of men,” that only increased after they denounced the sexual abuse of nuns by clergy.

The editorial committee of “Women Church World,” a monthly glossy published alongside the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano, made the announcement in the planned April 1 editorial and in an open letter to Pope Francis that was provided Tuesday to The Associated Press.

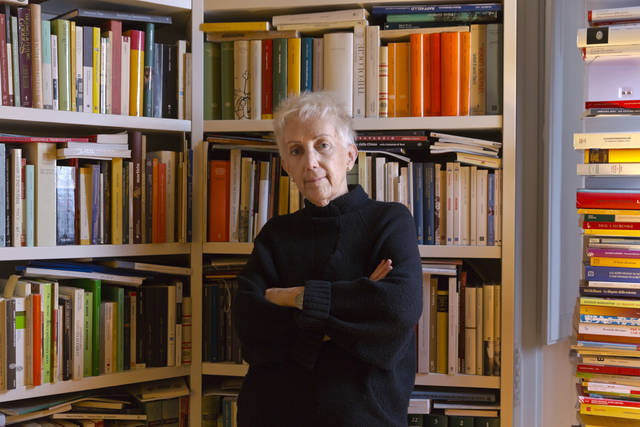

“We are throwing in the towel because we feel surrounded by a climate of distrust and progressive de-legitimization,” founder Lucetta Scaraffia wrote in the open letter.

In the editorial, she wrote: “We believe there are no longer the conditions to continue our collaboration with L’Osservatore Romano.”

The decision is a blow to Francis’ efforts to give greater decision-making roles to women at the Vatican, a pledge that has in some ways fallen flat despite increased pressures in the #MeToo era. Scaraffia had become perhaps the most prominent woman at the Holy See, even though she never drew a salary for her 7-year leadership of the magazine she founded, “Women Church World.”

Scaraffia told the AP that the decision to leave was taken after L’Osservatore’s new editor, Andrea Monda, earlier this year planned to take over as the magazine’s editor. She said he backed off after the editorial board threatened to resign and the Catholic weeklies that distribute translations of “Women Church World” in France, Spain and Latin America, told her they would stop distributing if she weren’t in charge.

“After the attempts to put us under control, came the indirect attempts to delegitimize us,” she told AP in a statement, citing other women brought in to write for L’Osservatore “with an editorial line opposed to ours.”

The effect, she said, was to “obscure our words, delegitimizing us as a part of the Holy See’s communications.”

In a statement, Monda denied having tried to weaken “Women Church World” and said that he merely tried to bolster other female voices and viewpoints on the pages of L’Osservatore. He said he always guaranteed the magazine’s autonomy, and limited himself to suggesting ideas or possible contributors.

“Seeking to avoid interference with the monthly insert, I asked for a truly free confrontation in the daily paper, not built on the mechanism of one against the other or of closed groups,” he said. “And I did so as a sign of openness and of the ‘paressia’ (freedom to speak truth) requested by Pope Francis.”

He said he took note of Scaraffia’s “free and autonomous” decision to leave, offered his thanks for her work, and pledged that the magazine would continue on “without clericalism of any sort.”

Scaraffia launched the monthly insert in 2012 and oversaw its growth into a stand-alone Vatican magazine as a voice for women, by women and about issues of interest to the entire Catholic Church. “Women Church World” had enjoyed editorial independence from L’Osservatore, even while being published under its auspices.

In the final editorial, which was sent to the printers last week but hasn’t been published, the editorial board cited L’Osservatore’s initiatives with other women contributors that they said constituted competing points of view “with the effect of pitting women against one another,” with the magazine’s editorial staff considered no longer trustworthy.

“Now it seems that a vital initiative has been reduced to silence and that there’s a return to the antiquated and arid custom of choosing women considered trustworthy from on-high, under the direct control of men,” read the open letter, signed by Scaraffia.

The departures are the latest upheaval in the Vatican’s communications operations, following the abrupt Dec. 31 resignations of the Vatican spokesman and his deputy over strategic differences with Paolo Ruffini, prefect of the dicastery for communications.

Scaraffia, a history professor and journalist, was perhaps the most high-profile woman at the Vatican, an avowed feminist who nevertheless toed the line on official doctrine. She frequently ruffled feathers, though, with her lament that half of humanity — and the half most responsible for transmitting the faith to future generations — simply is invisible to the men in charge of the Catholic Church.

She stoked uproar in February when, on the pages of the magazine, she denounced the sexual abuse of nuns by clergy and the resulting scandal of religious sisters having abortions or giving birth to children who are not recognized by their fathers.

The article prompted Francis to subsequently acknowledge, for the first time , that it was a problem and that he was committed to doing something about it.

Prior to that issue, the March 2018 issue was perhaps its boldest, denouncing the servitude of religious sisters who work for next to nothing to cook and clean for bishops and cardinals. The issue raised eyebrows for sure, but Francis himself had raised the very same issue only a few months before.

The articles on the religious sisters struck a chord globally, giving voice to suffering that has long been silenced because of nuns’ vows of obedience, their ingrained deference to clergy, second-class status in the church and fear of shame, scandal and reprisal.

It remains unclear what the future will bring for the magazine internationally. The Spanish editions are published and distributed in Spain and parts of Latin America by the Catholic publication Vida Nueva; the French edition is published as an insert to La Vie, a Catholic weekly.

Circulation of the Italian magazine is estimated at around 12,000, plus its online viewership.

———

This version corrects the lead quote involving “throwing in the towel” to note that it is from the open letter to the pope, not the editorial.